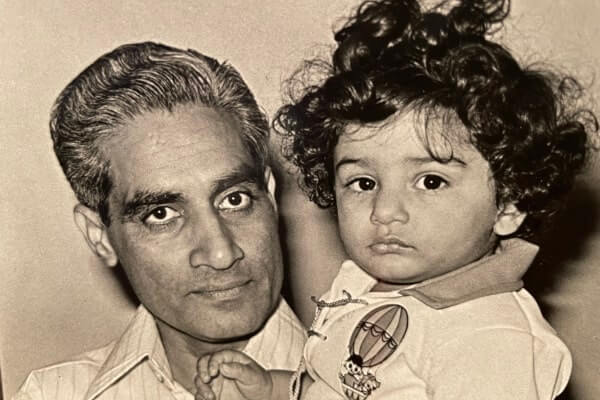

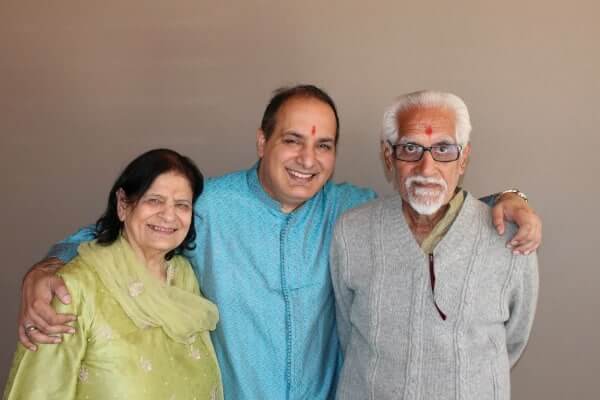

‘My dad, in his own words’ is a series paying tribute to our fathers, just in time for Father’s Day. We asked children in various age groups to interview their fathers, showcasing the intergenerational bond between them and celebrating the wonderful and eventful lives they’ve both had. Here Vivek Bhatia 50, CEO and Managing Director of Link Group sits down with his father, Kimtilal Bhatia 95, former corporate executive.

Vivek Bhatia: Tell us about your childhood.

Kimtilal Bhatia: I was born in Gujranwala in 1928. My father was a rice merchant and mill owner, and my mother was a homemaker. My brother was two years older than me.

Those days, there was little means of distraction, and hardly any homes had electricity. Most people depended upon agriculture for livelihood and were generally content with what they had. There wasn’t much of a rat race then, and we were happy being together and looking out for each other.

We lived in a small town with 90,000 people who were mostly connected to each other. It felt like one large family, and we seldom heard about crimes being committed. Money was important for the basics, but desires were limited, and everything wasn’t as commercial as it is today.

To give you an idea of prices of at that time – a litre of milk used to cost two annas (1/8th of a rupee or 12.5 paise), you could rent a house for two rupees a month, and the price of Gold was Rs 25 per 10 grams (“tola”).

Those were the good days!

Vivek Bhatia: What was it like during the partition?

Kimtilal Bhatia: When independence from the British Raj was declared, there was widespread celebration. I was 18 and as a teen had participated in many freedom rallies and activities. However, the announcement of the partition was a huge blow to us. All around, there were riots, arson, looting and killing of innocent people. Unfortunately, we saw people at their worst, like monsters; it was very difficult to witness such terror and little regard for human life.

We lived in an integrated community with Muslim neighbours who were like family and looked out for us in the chaos. In July, we left Gujranwala via train to Lahore and then to Meerut, where my maternal uncle used to live. We couldn’t take much with us – some kitchen utensils, a handful of clothes and whatever little cash we had. It was just my mother, brother, and I as my father had passed away a few years ago.

We’d always hoped to go back home once the chaos settled but as time passed, it dawned on us we’d be here permanently, on this side of the border. We had to begin our lives again and initially we didn’t feel very welcome. People treated us as strangers in our own country and eyebrows were raised when they discovered you came from across the border. Having said that, we were fortunate unlike millions of others who had to live in refugee camps and lost loved ones.

The entire experience was traumatic – for decades, all the country had strived for was independence from the British. However, the way it came about was bittersweet for people who were uprooted from their lives (on both sides of the border) due to the partition of the country, which had (and probably still has) such a huge human cost.

Vivek Bhatia: Tell me about three good decisions you’ve made in life.

Kimtilal Bhatia: Growing up during the freedom struggle, I always wanted to join the armed forces. Post independence, when I was 19, I tried but wasn’t successful. I then pursued journalism and wanted to be a foreign correspondent, but that didn’t work out either.

I finally discovered my passion was understanding people, and in 1956, with encouragement from my mother, I went to London to study Personnel Management (which is now called HR). When we lived in Gujranwala, there was only one person there who was educated overseas, and my mother wanted one of her children to do the same.

In 1984, when I was 56 and about to retire, I left my role as divisional head of an automobile company to set up a small-scale manufacturing factory. This meant moving the family from Bombay (as it was called then) to a small town called Aurangabad, about 400 kms away. You were still in school, and I realised that I’d need to work for another 10-15 years to sustain your education. It was impossible to do this in the corporate sector, so necessity motivated me to start something new late in life.

In 1999, you decided to move to Australia. It was tough for us to be so far away, but your mum and I backed your decision wholeheartedly.

We moved to be close to you in our 80s, which came with a lot of adjustment and trade-offs. However, watching the grandkids grow has been worth the displacement.

Vivek Bhatia: What are you most thankful for?

Kimtilal Bhatia: For my parents, whose love and guidance has made me what I am today and helped me face life’s ups and downs.

For the challenges in my life – losing my father when I was 10, being uprooted from our home at 19, changing careers at 56, moving countries in my 80s, being stuck in India during COVID and losing my life partner after being together for 56 years. These challenges have taught me resilience, not to fear hard work, to dig deep when things look bleak and to back yourself even in the most adverse circumstances. I hope I have passed on those life learnings to the next generation.

For my spirituality – I have strong faith in God, it was indoctrinated in me as a young child by my mother. I believe that God has always stood by me and guided me throughout life’s various stages. I have also found peace of mind in yoga and meditation, and I’m very grateful for this integral part of my life.

Vivek Bhatia: What do you like about Australia?

Kimtilal Bhatia: I fell in love with Australia almost immediately when I came here in 2001. It’s such a beautiful country with friendly people, who have laid back and happy-go-lucky attitudes.

I admire the socialist nature which ensures a good standard of living for all. The social security net, especially through Medicare, is a key pillar that differentiates it from many other countries.

I have enjoyed reading about the country and met many helpful people during our travels around Australia. I also admire the adherence to law and order, and that it is the same for all people irrespective of who they are.

It’s a great place to raise a family and there’s a reason it is called the “lucky country”.

Vivek Bhatia: What do you think about the current state of India?

Kimtilal Bhatia: Growing up, my idol was Shaheed Bhagat Singh. When the Quit India movement started in 1942, I was 14 and like other teenagers joined the freedom struggle. I asked someone I knew to show me the inside of a jail, so I could see how it would have been for him, Rajguru, and Sukhdev during their final days.

I’ve always been a keen observer of politics, administration and nation development and have followed the Prime Ministers from Nehru to Modi. The progress we’ve made in 76 years makes me a proud Indian. Last week’s landing of Chandrayan-3 on the moon was a moment of immense pride for the entire nation. I have no doubt the future belongs to India, and it will re-emerge as a global superpower, turbocharged by its young population.

However, I’m saddened by how we have evolved as a society. We have forgotten community, family orientation, supporting each other and doing the right thing, adopting western practices of consumerism, selfishness, and materialism.

Unfortunately corruption, which started as early as the 1950s with Licence Raj, is eating into the soul of the nation. There needs to be a systemic mindset change to cleanse ourselves from this malaise. Integrity and doing the right thing need to be the core tenets of who we are. There’s been very little national character building and it’s time it becomes the focus for all.

The wide chasm between the haves and have-nots pains me. We celebrate how many billionaires there are in India as a mark of success, but the true definition of success is raising the quality of life for your most vulnerable. There is so much to be done to bring the most vulnerable sections of our nation to bare minimum living standards. Some patchwork in motion and bandaids are being applied for the short term, but we need serious rewiring and fundamental shifts to restore the country to its former glory.