In 2017, Charan Dass arrives at his job interview for Rom Control, an industrial electronics service centre in Southeast Melbourne. He wears a reasonably well-ironed white collared shirt and his loose brown trousers balloon over his unbranded running shoes.

The manager leads him to a faulty mechanical instrument and asks Dass to diagnose the fault. He completes this trial shift within half an hour, and that evening, he’s offered a full-time position.

It’s an enviable but unremarkable result for a migrant of two years. Except at the time, Charan Dass, was 72 years old, held no formal qualifications, and until two years ago, didn’t speak a word of English.

Whether you call it luck, hard work, or God-given talent, such instances are frequent in the life of Charan Dass. This is the story of how an otherwise ordinary man, an unlikely candidate without vast sums of money or fame made extraordinary contributions.

From humble beginnings

Growing up in Haryana in the 1950s, Dass’ family couldn’t afford school. His teachers supplied his tuition fees and uniform, and each day, he’d walk seven kilometres to school.

His family planned for him to leave at Standard 5 to work in a nearby town, but his teachers saw potential in him.

“I told my headmaster this is the end of my studies, but he said, ‘you are the topper, you must go’,” says Dass. “Without telling me, he sent a notice to my parents about my marks, saying if they don’t admit me to higher class, the police will catch them. My parents were so scared they agreed.”

Maintaining his stellar academic record, Dass left school at Standard 10 to serve in the Indian Army. At that time, the fledgling nation was amid a volatile conflict with its neighbour Pakistan.

But Dass needed to provide for the family.

“When I joined, it was a terrible time, but I thought if I don’t serve, my family will be in a horrible state living hand-to-mouth. It was do or die, so I opted to join the army, whatever it was, because it was easy – you just had to be a volunteer,” he says.

“Because of my marks, the army made me a wireless mechanic – I had no idea what this was. We were sent to Jabalpur for training and that train ride was my first journey away from my family.”

Though the least developed recruit in age, physicality, and qualifications, Dass thrived in technical training.

“I was very curious and listened to every word the teacher spoke. I’d never heard of such technical words, and I mugged them up in the evenings. The teacher would ask questions and only I answered because I had mugged up; there was a Board of Honour and my name was always on it,” he says.

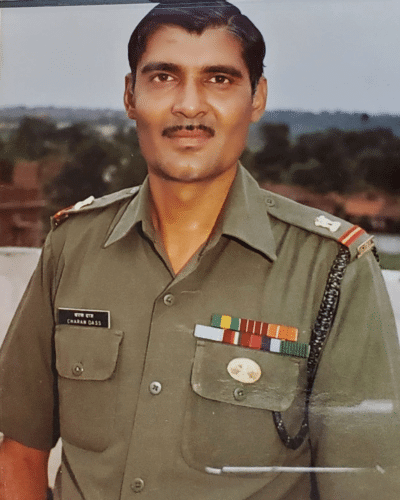

From 1966 to 1993, Dass’ Signals department was posted everywhere from Siliguri to Botswana. He would repair countless wireless communication devices, working his way up to Subedar Major. Dass was cherished by his peers throughout his 28 years of service, receiving a Chief of Army Staff Commendation Medal for his efficiency during the 1971 Bangladesh war.

After his service, Dass and his wife Angrezo settled down in Delhi, passing time in an engineering job for a year before retiring in 1995.

Second wind

Twenty years later, in 2015, Dass and his wife would follow their children and migrate to Melbourne.

“We were growing old and thought we should be with them in case we fall sick,” he says.

Having only studied until Standard 10, Dass’ English vocabulary was limited to the technical terms he’d learnt in the army. He was confined to his home, struggling to perform everyday tasks such as shopping.

Eager to participate in the community, he attended Adult English Migrant Program classes in Heidelberg West, where he again soaked up the knowledge.

“I was a big learner; I asked my teacher to let me attend not only my classes but all the classes,” says Dass. “After a month, I impressed them so much they gave me a scholarship to study English over 500 hours without fees. When I gave the final test, the trainer took my photograph for his office because I was the first person over 60 to have ever been trained.”

It was around this time Dass’ son listed his father’s details on Seek, and the Electronics Engineer position appeared at Rom Control – astonishingly, this was Dass’ first and only interview since arriving in Melbourne.

Again, he was the outlier, nearly 40 years older than his colleagues and without the formal qualifications they had. But within a month, ‘Charan Dada’ became the go-to man for the trickiest repair jobs.

Three months into the job, Dass built a jig to test load virtually rather than manually, the first of its kind in Australia. It eliminated the to-and-fro process of customers returning their equipment for fine-tuning, considerably streamlining the repair process.

“I had basic knowledge of electronics and my experience, so that’s how I designed it,” says Dass. “For 12 years, the manager had never given any incentive to his workers, but that year he was so happy he held a Christmas party and gave me a $1000 bonus.”

‘Charan’ at heart

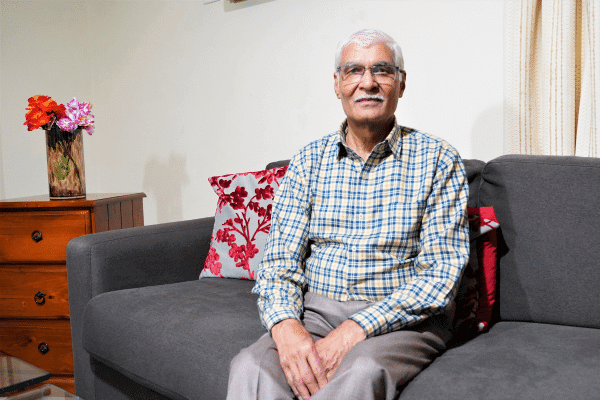

Now aged 75 and living in Melbourne’s Southeast, Dass has relaxed his ambitions, but plans to keep contributing to the workforce.

“I’m saturated at this point; I’m going to complete 76,” he says. “I’m happy to pass time and not take much stress. I’m content; I want to keep working as long as my organs are.”

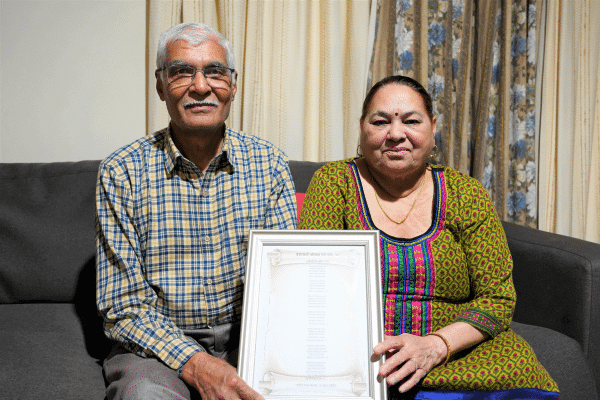

Arriving a stranger in Australia, Dass’ diligence and humility has garnered him an army of friends and supporters; in 2021, the Northern Region Indian Seniors Association (NRISA) awarded him a Community Service Award for Exemplary Settlement as a New Migrant, and Dr Santosh Kumar OAM heralded him ‘a lamp post to guide all struggling migrants’.

But in a lifetime of extraordinary contributions, Charan Dass’ greatest legacy is his impact on around him. At Rom Control, stories of his time working there are retold with fervour by his colleagues and apprentices. Despite leaving the company in 2021, he spends his weekends repairing electrical components for them, free of charge.

“I can’t stop myself when they are in need – all it takes is my knowledge,” says Dass. “I always think, instead of why give, why shouldn’t I give?”

In Hindi, the name ‘Charan Dass’ describes someone who ‘sits at the feet of god’. True to form, Dass feels strongly about serving others with his ‘God-given talent’.

“It is my mindset – whatever I do, I should do it for humanity. If somebody can gain from my outcomes, my blessing to them.”

READ ALSO: Dr Santosh Kumar, OAM: Seniors are a valuable community resource