The women of the famed literary family from Bengal were harbingers of change in their own right, writes MADHUSREE CHATTERJEE

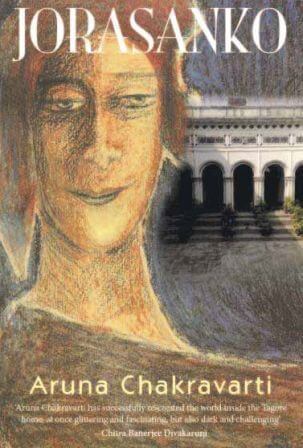

At a time when the struggle for a world that is safe for women is in the news, here is a book that is timely, even as it retells history. Aruna Chakaravarti, a 2004 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize nominee, recalls the contribution of the Tagore women to the modern women’s movement in her new book Jorasanko (Harper Collins India). Jorasanko is the name of the Tagores’ ancestral home. Jnanadanandini, wife of Satyendranath Tagore, elder brother of poet Rabindranath Tagore and the first Indian to enter the Indian Civil Service in 1863, was the force behind the opening of the zenana (area where women were kept in seclusion) in the traditional elite households of 19th century Bengal. She was the first woman from a feudal family to accompany her husband to his place of work. After a one-and-a-half year stint in Bombay, as Mumbai was called, where her husband was posted as assistant collector, Jnanadanandini brought the “Parsi way of wearing the sari” to Bengal.

The sari was earlier wrapped around the bodies of women in a single sheath without pleats or a shoulder drape. But Jnanadanandini wore it the way it is draped today, with pleats around the waist and the fabric gathered into a drape to cover the “breasts and the shoulder”, making the woman look elegant. The feisty wife of the civil administrator was also the first one to wear the Oriental dress – a Mughal style kurta (shirt) and voluminous pants – to travel. The light-eyed Jnanadanandini, described as “mealy mouthed” by her mother-in-law, introduced the nuclear family within the very walls of Jorasanko, adopting the western way of life. Chakravarti’s account reads like an absorbing family soap, and one might be forgiven for forgetting that the work is non fiction. The work examines other women in the Tagore household too.

Sarada Sundari, wife of Debendranath Tagore and mother of poet Rabindranath, suffered the throes of seeing family values change. The rather plain woman, who commanded the Tagore household and a dashing husband, refused to let the “old world conservatism slip by”. A little indolent and lazy, she rebelled against daughter-in-law Jnanadanandini. Sarada’s sister-in-law Jogmaya was a total contrast to her. Though second in the hierarchy of women in the household, she was the one who looked after all needs of the family. She proved an excellent mother to not only her own children, but to Sarada’s as well, Chakaravarti holds. Of Tripura Sundari, who was not exactly renowned for her beauty, the author says condescendingly that she made up for the lack of beauty “with her tireless work of household management” … “She had the strength and energy of the barren woman and all her heartache … Though she received a lot of commendation, it failed to satisfy her”.

Digambari, wife of pioneer Dwarakanath, Rabindranath’s grandfather, is painted as stoic. She bore her husband’s absence without complaint, and the force of her character surprised even Brahmin pundits. Driven by the urge to “atone for her husband’s sins” of moving into a new home from ancestor Jnanadanandini, wife of Satyendranath Tagore, elder brother of poet Rabindranath Tagore and the first Indian to enter the Indian Civil Service in 1863, was the force behind the opening of the zenana in the traditional elite households of 19th century Bengal. Neelmoni Tagore’s abode, for his association with British rulers and for the pleasures he sought in nautch girls, Digambari locked herself in the prayer room. In contrast, Kadambari Devi, the wife of Jyotirindranath and sister-in-law of poet Rabindranath, was a melancholic and gentle woman with deep sensitivities, refined intellect and an insatiable thirst for knowledge. She was driven to end her life. “Mrinalini was salt-of-theearth”, the silent force behind husband Rabindranath’s meteoric rise in the literary world.

What the writer perhaps forgets to add is the contribution of the petite former Bollywood actress Sharmila Tagore, the widowed begum of Nawab Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi, and great-grand daughter of Rabindranath Tagore. Sharmila was symbolic of the family’s continued presence in the new popular cultural milieu of cinema in India. And in a strangely karmic way, she was also the family’s tenuous tie to its ancient secular roots, the Pirali Brahmins of Jessore, who were ostracised by their Hindu brethren for allowing their blood brothers to convert to Islam and bringing the two faiths together nearly five centuries ago.