Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s leadership, the Bharatiya Janata Party government has put forward several anti-Muslim policies. The latest is a clampdown on what it sees as “love jihad,” the belief that Muslims are seeking to deceive Hindu women through marriage and convert them to Islam.

Over the course of the past year or so several BJP politicians have suggested that this is part of an Islamic conspiracy to increase India’s Muslim population.

More recently, one of India’s most populous states has assumed the right to intervene in matters of marriage – particularly between a Hindu woman and a Muslim man. Other states are planning to follow suit.

A new law on marriage

As a political scientist, I see the rapid growth of religious tensions/conflicts in India as a continuation of BJP’s anti-Muslim policies.

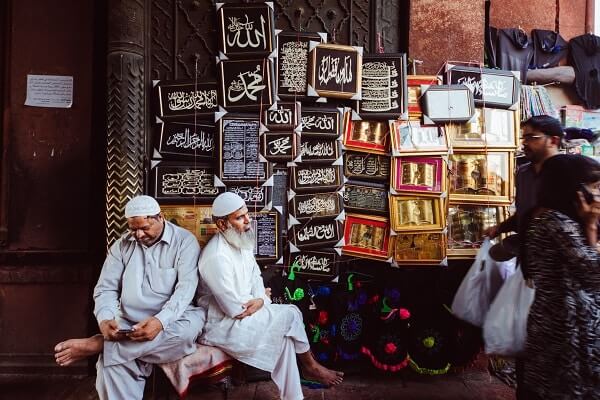

Despite being a Hindu-majority country, India is home to nearly 200 million Muslims.

Since the BJP came to power with a clear majority in parliament in August 2019, it stripped the special provisions in the Indian Constitution that had granted a substantial degree of autonomy to India’s only Muslim-majority state, Jammu and Kashmir – now a Union Territory, an arrangement in India’s federal dispensation under the direct rule of the national government.

In 2019, the Indian government also passed the Citizenship Amendment Act, which eases the pathway to citizenship for a range of religious groups from India’s neighboring countries but excludes Muslims.

READ ALSO: Citizenship (Amendment) Bill 2019: How, Why and What?

Now, in its latest move, India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh, where about a fifth of the population is Muslim and the state government is led by the BJP, has taken to policing the private lives of its citizens. In November, the state passed the first “love jihad” law in the country.

Known as the Prohibition of Unlawful Religious Conversion Ordinance, it requires couples from different religious communities to provide two months’ notice to a district magistrate before getting married. A district magistrate is an official belonging to India’s administrative services – a vestige of the British colonial rule – who is in charge of the district, the basic unit of administration, and has legal as well as significant executive powers.

Under the terms of the ordinance, the presiding judicial official would have the discretion to decide whether the conversion was through compulsion; the offending person could then be denied bail and sentenced to 10 years in prison. The irony of this issue is that few individuals routinely choose to marry outside their religious affiliation.

Notionally, this law applies with equal force to all interfaith marriages. However, for all practical purposes this would affect Muslims, as Islamic personal law requires a non-Muslim to convert to sanctify the marriage. So far, enforcement has targeted only Hindu-Muslim marriages. Since its passage last year, as many as 30 Muslim men arrested in Uttar Pradesh are facing possible prosecution. It remains unclear at this stage what sanctions Muslim women marrying Hindu men might confront.

Following the lead of Uttar Pradesh, four other BJP-ruled states introducing similar legislation. In late December, the central state of Madhya Pradesh passed the Freedom of Religion Bill, which would also place similar restrictions on interreligious marriage. This law also holds the possibility of 10 years’ imprisonment.

Since the BJP holds a majority in the state legislature, there is a strong possibility of this becoming a law. Thus far there has not been any effort to enact a national law. Currently, the BJP rules in 16 out of India’s 29 states, and several other states are said to be considering enacting such a law.

Anti-conversion fervor

The strong opposition to any kind of conversion goes back to British India. In the 1920s, a Hindu revivalist movement known as “shuddhi” emerged. It sought to reconvert those who had chosen to embrace other faiths, most notably Islam. At the time interfaith marriages were a rarity.

The movement had a strongly patriarchal tenor and portrayed Hindu women as hapless victims of the ruses of Muslim men. This movement, while it initially acquired a degree of support, faded out as other more compelling social and political issues, such as anti-colonial nationalism, came to the fore.

A somewhat similar fervor, I argue, has now returned in independent India. Apart from this legislative onslaught, two other recent incidents in particular bear particular mention.

The first involved a television advertisement for a high-end jewelry chain that was launched on Indian television in October. The advertisement was from Tanishq, an affiliate of one of India’s largest conglomerates, the Tata Group, and was titled “Ekatvam,” or “unity” in Hindi.

The advertisement depicted a Hindu woman and a Muslim man preparing for a wedding. As soon as the advertisements were aired, some Hindu activists protested vigorously on social media. The company, fearing violence, withdrew the advertisement altogether.

READ ALSO: Tanishq advertisement: a time to stand together

The other episode took place in November when Netflix aired BBC’s adaptation of the novel “A Suitable Boy” by the acclaimed Indian writer Vikram Seth.

Once again, some Hindu activists protested because it depicted a Hindu-Muslim couple’s passionate kiss. The activists claimed that the film was “encouraging love jihad” and had “hurt religious sentiments.”

Accordingly, they demanded that it be forthrightly withdrawn. A minister in the state of Madhya Pradesh lodged a formal police complaint against the showing of the film, and further investigations are on.

READ ALSO: Hijab and the workplace

The perils of modernity

Urban couples in India are increasingly stepping out from the tradition of arranged marriages and choosing their own life partners, sometimes across religious lines. No previous government has sought to regulate such choices. However, under the Modi government, right-wing Hindu groups are harassing such couples.

Activists have spoken out vigorously against this tide of vigilantism, and some regional courts have questioned the very basis of a law that encroaches on individual freedoms.

However, at a time when personal choices are under attack, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has maintained a studious silence.

is a Professor of Political Science and the Tagore Chair in Indian Cultures and Civilizations at Indiana University.

This article first appeared in The Conversation. You can read it here.