Pawan Luthra: The East India Company changed from ‘an empire of business, into the business of empire’. How did they do this?

William Dalrymple: The Company for its first 150 years is just a trading company. Because the Mughals are not particularly interested for some reason in exporting their goods, the Company steps in and acts as the shipping agent. It does very well. It beats local competition because it has better ships and it sells this stuff around the world. Then in the 1750s, two things happen that change the nature of everything.

The first is that the Mughal Empire has disintegrated. It reaches its peak under Aurangzeb, who dies in 1787. Shortly after that, the Persian emperor Nadir Shah defeats the Mughals at the Battle of Karnal, captures their Emperor Mohammed Shah Rangeela, marches him into Delhi, and six weeks later, leaves with 8,000 wagons filled with jewels, gold and silver, everything, in a single looting expedition back to modern Afghanistan. He takes the Peacock Throne in which is embedded the Koh-i-Noor.

He takes the Daria-i-noor, the other great Mughal diamond, which is now in the Kremlin in the sceptre of Catherine the Great. All this stuff just debauches off to the Hindu Kush. It’s as if you just poured a fire extinguisher into the local boiler.

For an art historian, this is one of the most wonderful periods of Indian culture. For literature, for painting, for music, for Indian dance, this is one of the most dramatically prolific and culturally fascinating periods of Indian history.

But politically, it means that the Mughal Empire, which was this unstoppable force of four million men under arms, has now fragmented into lots of little kingdoms. And not just the British or the English East India Company, but the French companies, between the two of them, begin hoovering up these little tiny states, which are culturally and economically very rich, but which are militarily and politically vulnerable. The French show the way in 1740: they are the first to train up sepoys, local Indian soldiers, in the latest military technology from Europe.

Europe has just fought two big wars – the war of the Austrian Succession and the war of the Spanish Succession – and Frederick the Great of Prussia who’s a military genius has transformed warfare with simple little changes to the nature of the cannon. He puts an elevating screw on the back of a cannon. He makes them portable so horses can move them around battlefields. He invents a form of musket that has a bayonet and which can be rapidly loaded and fired in file firing – one line kneel down and fire as the next lot load, than that lot fire, so that you get continual firing by infantry.

These techniques, none of which are rocket science, are quite easily copied and are brought to India by the French and they train up local guys to do it. And it’s incredibly effective. The first time it’s tried out is in 1740, at the Battle of Adyar, which is now southern Chennai. 70 French company sepoys see off 3,000 Carnatic cavalry. From that point, for about 30 years, the English and the French realise they can more or less see off an army with this new military technology. The English company then tries this out in Bengal with Siraj-Ud-Daula at the Battle of Plassey, then again at the Battle of Buxar in 1764.

To everyone’s amazement, most of all to the Company’s amazement, they haven’t planned this particularly. They found that using this new military technology, they are in a position to just take over north India. This incredibly rich, incredibly civilized, but now vulnerable, fractured and disunited kingdom is simply conquered in as little as 50 years. And how they do it is astonishingly audacious.

East India Company trains up local Indian warriors to use this new technology. The Company sepoys grow from 20,000 at the time of Clive to 50,000 by the time of the Battle of Buxar, and only forty years later in 1799, to 200,000 sepoys. Which is literally double the size of the British Army. The British Army, which is barely involved in India at this point, is only 100,000 men and is now engaged in the struggle with Napoleon. But the Company which only has thirty-five people in its head office, and in Bengal never has, even as its peak, more than 2000 white guys sitting in Bengal, train up 200,000 Indians to fight other Indians.

To do this, they borrow money from Marwari and Hindu bankers.

If you wrote this as a novel or a film script, you’d be laughed off because it’s the most improbable story.

Why would anyone fight their own brothers and sisters? Why would anyone lend money to a voracious corporation that was involved in something so violent? Well, the answer is, the soldiers got paid twice the salary of any other military unit in the country.

And why would the Marwari traders and the Hindu bankers of Benares, Allahabad and Patna lend money to the Company? The answer is in that case, that it may have been foreign as in it was Christian, meat-eating, white-skinned, from Europe, but as far as the Marwari money lenders were concerned, they were both financiers, they spoke the same financial language, they understood about repaying loans on time with interest, they had civil courts where business contracts could be defended and upheld.

Calcutta initially was like Dubai or Singapore today. It was a tax haven where you could escape tax you had to pay elsewhere. You could grow and cultivate fortunes, which is what the Marwaris were doing. The Marwaris, originally from Marwar in Jodhpur, went to Calcutta for the same reasons people go to Dubai and Singapore today. They didn’t have to pay tax.

The East India Company is quite ingenious in realising that and playing on that. So the next thing it does in the 1790s, is it begins to break up the old Mughal estates, huge areas of land, and puts them up for auction. Who buys this stuff? The new rising Hindu middle-class families like the Tagores, the Debs, the Mullicks. And by buying into this world, they become part of it.

They get subsumed into this Company world and they make the decision, rightly or wrongly, that the Company which may loot assets, strip, plunder and be incredibly violent to its enemies, is for them the least bad option financially, that their capital is safe with it, and that they prefer it to the Mughals or to the Marathas. (The Marathas raided Bengal in 1740, looted, raped and pillaged. So they’re not going to go with those guys.) And Bengal, as this industrial hub, has the resources: it paid for the Mughal Empire first and then it paid for the Company.

It’s a horrifying story from a variety of fronts. Think Avatar – the movie where, you know, the mining company goes and takes over another planet. It’s the same sort of story. It’s a very canny, ruthless corporation that manages by military force and by financial inducement.

Pawan Luthra: You mention the Marwaris – or the JagatSeths as the Mughals called them, the Rothschilds of India as you call them. You claim that they lent the East India Company money to take over India and exploit the Indians themselves. How has contemporary India reacted to this statement of yours?

William Dalrymple: Well, I don’t think the Marwaris would have seen it like that. They would not have seen themselves as funding the expansion. The first thing the Jagat Seths do is actually pay Clive to topple Siraj-Ud-Daula.

It’s a palace coup that they’re paying them for and they don’t calculate on the Company then being the puppet masters. But the Hindu bankers continue to fund the Company because they see it as the safest place for their capital. It’s that simple. They’re businessmen. They have to make a judgment on which is the most profitable. Who is going to repay their loans? The answer is the Company will appeal. Business is pure business.

They see it as they do today. For the Company ultimately, its initial success is due to military superiority. Its final success is due to two things. One, it has Bengal with all its revenues, and two, the bankers back it rather than (other forces at the time). It’s that simple.

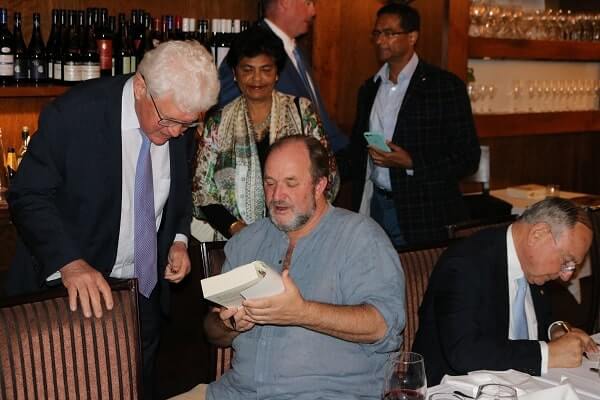

Photo Credit: Rinto Antony

Continue reading: William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy: A story of how far corporations can change the world