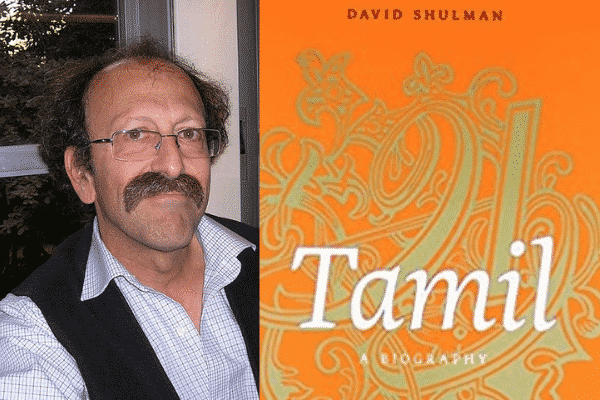

It was quite by accident that I stumbled upon a prodigious and erudite scholar of India – especially southern India, during one of my recent trips to India. The book, in bright orange, titled Tamil: A Biography beckoned me from the bookshop display shelves, and as I began thumbing through it, I was drawn irrevocably into it and found myself searching for, and devouring books by David Dean Shulman, the scintillating Iowa-born academic who had made Jerusalem his home, and on the way had learnt and mastered several Indian languages and their literature.

Shulman has written a series of deeply scholarly and engaging books on southern India. However, his magnum opus is arguably Tamil: A Biography (Harvard 2016), a detailed account of one of the few ancient languages that has survived more than two millennia in more or less its original form among its 80 million speakers scattered around the world. Shulman even traces some words in the Hebrew Bible that have Tamil origins!

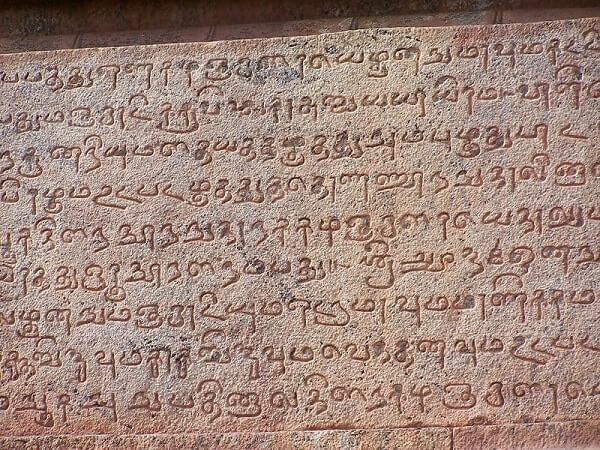

Some broad and distinct time periods emerge from Shulman’s history of Tamil. The first, historically pivotal period is the one of consolidation of Tamil’s very unique mode of speaking, writing, singing and thinking, beginning with the earliest extant work Irayanar Akapporul right up to the Sangam period marked by such great works as Silapadikaram. The early chapters are filled with delightful verses and prose translated from several ancient texts by the author, and numerous renditions of the lives and words of sages, poets, scholars and even Gods who elevated Tamil to its exalted status.

The second ‘blossoming’ occurred at the time of devotional outpourings of Vaishnava Alwars and Saiva Nayanmars, which in his view is the ‘single most powerful contribution of Tamil to pan-Indian civilization” – and their influence as a shaping force within Hinduism. After throwing light on the Vaishnava saint Nammalwar, the author of the ‘Tamil Veda’, Tantric Bhakti saint-poets, and the role of Saiva Siddhanta mutts in the Kaveri delta, he emphasises their role in de-linking the language from Brahmanical moulds – and in unleashing popular devotion in the vernacular in the whole of India. Saint-poets Andal and Karaikkal Ammaiar shine as almost early feminists!

The book then describes three centuries of Chola-era globalisation and the spread of Tamil beyond southern India to south-east Asia and China as the language used by merchants and monks (one can find evidence in the large number of Tamil words in Malay and Bahasa). Kamban’s Ramavataram, seminal Jain and Buddhist works such as Seevaga Chintamani and Kundalakesi – give us a glimpse of the syncretic culture of the times and the contribution of these religions to Tamil.

Shulman demonstrates – convincingly, and contrary to popular misconceptions – that the post Chola period, between the 13th and the 16th centuries, was one of ‘continuous creative experimentation’ citing the works of Kalamega Pulavar, and the emergence of a synthetic register, Manipravalam in southern Indian languages, a complex synthesis of Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam and Sanskrit. Through his examination of such works as the Kovil Ozhugu or Temple Register of the Srirangam temple, and record keepers and local historians such as the karnams, he demonstrates that contrary to colonial and popular misconceptions, there existed a rich corpus of written material and record of history in southern India.

Shulman falters when he tries to grapple with the emergence of Tamil modernity, although he pays rich tribute to U.V. Swaminatha Iyer, who along with other scholars rediscovered lost texts in the 19th century, and made it possible for us to access those ancient treasures today. He omits several renowned modern Tamil authors and poets. That aside, it is impossible not to be impressed by his scholarship and research overall.

What Shulman demonstrates clearly is that the classical languages of southern India have been intimately interwoven for centuries. A pure, autonomous Tamil never existed, he argues, and warns against using such notions for political ends. The reality is that both Sanskrit and Tamil have jostled with, and borrowed from each other over the ages: one need only cite the examples of Sage Agastya who is said to have brought Tamil from the Himalayas; the great poet Dandin who is said to have bridged the language gap between Sanskrit and southern Indian languages in the Sangam era; the 17th century Tamil Saiva saint Kumaraguruparar, who went to Kashi to re-invigorate Saivism there, and became a Sanskrit scholar in the process.

One feels that this book needs to be read by all Indians, not just Tamils, for there is a lesson in this for politicians from northern India as well – when they read books such as this, they will hopefully, develop an understanding of the Tamil language and history, and an empathy for the sentiments of a people who have preserved and nurtured with love, their mother tongue through more than two millennia, and why they are passionate about it.

However, I fear it is not a book that is easily accessible. It employs complex language and academic concepts that may put off most readers – so my fear is that, sadly, not many will read it. Hopefully, David Dean Shulman can bring out a simplified and condensed version of this book for lay readers worldwide.

READ ALSO: ‘Stories of Kannagi’ earns judge’s nod at Blake Art Prize

You may have noticed Indian Link news updates are no longer available on Facebook.

Until we’re back on Facebook, here are other platforms you can find our content on and follow us:

Indian Link News website: Save our website indianlink.com.au as a bookmark.

Indian Link E-Newsletter: Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter.

Indian Link Newspaper: Pick up up a copy at your local spice store, or click here to read the e-paper

Indian Link app: Download our app from Apple’s App Store or Google Play and subscribe to the alerts.

Twitter: Follow us at twitter.com/indian_link

Instagram: Follow us at instagram.com/indianlink

LinkedIn: Follow us at linkedin.com/IndianLinkMediaGroup

YouTube: Subscribe at youtube.com/c/IndianLinkAustralia