When Swayam Ganguly first saw Mad Max (1979) as a kid he was hooked. But the passion for Australian cinema grew much later on in life for him.

Ganguly, an ardent film enthusiast and corporate film director, has meticulously compiled over 1,000 intriguing trivia tidbits for cinema lovers into his new book Chambers Book of Cinema Facts (Hachette India). His book spans lesser-known details from Bollywood, Hollywood, and global cinema, making it a must-read for moviegoers, cinema history buffs, quizzers, and newcomers eager to explore the captivating world of films.

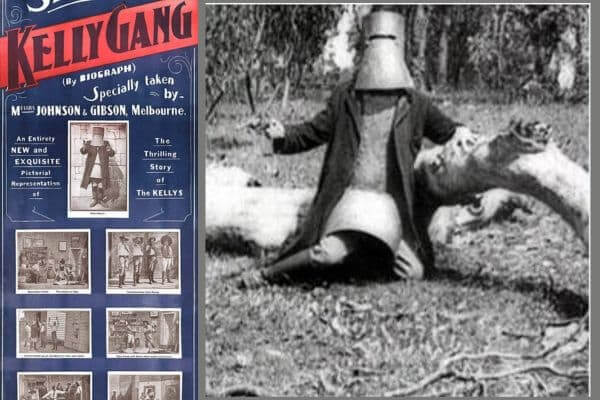

Detailing the origins of the industry which first sparked his interest in film, he writes about the lesser known impact of The Story of the Kelly Gang, which premiered at the Athenaeum Theatre in Melbourne on Boxing Day in 1906. This hour-long film depicted the life of the notorious 19th-century bushranger Ned Kelly and his gang, who terrorised the people of the north – eastern district of Victoria.

Interestingly, this film is recognized as the world’s first feature-length movie. Its release, however, stirred controversy due to its sympathetic portrayal of the gang, and over time, the film was largely destroyed. But, fragments were rediscovered in 1975 and subsequently restored.

In his new book, Chambers Book of Cinema Facts, Swayam Ganguly highlights this film’s significance as a catalyst for Australia’s burgeoning film industry.

“‘The Story of the Kelly Gang’ is a very important Australian film, not only for the commercial and critical success enjoyed by it,” Ganguly begins telling Indian Link. “But it has inspired many films later based on the legend of Kelly. It is also regarded as the origin point of the ‘bush- ranging’ drama, which is an important and fascinating genre that dominated the early years of Australian cinema inspired by this great film.”

Australian Cinema: The Beginnings

A whole chapter in the book is simply dedicated to Australian cinema.

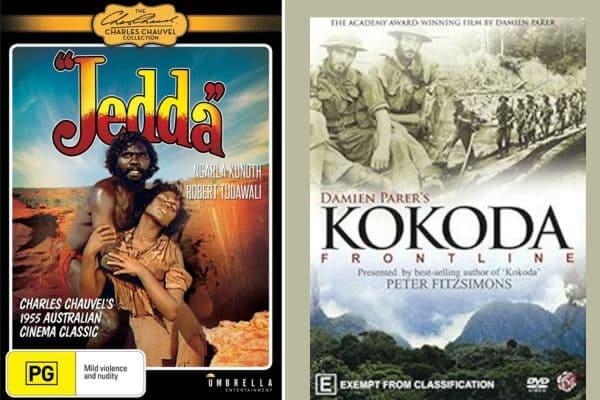

For instance, Swayam Ganguly’s book notes, Jedda (1955) was Australia’s first-ever feature film in colour and also the first one to be featured at the Cannes Film Festival. “With a cast of non-professional Aboriginal actors, the movie was about a young Aboriginal girl growing up in a closed white community,” the book highlights.

Kokoda Front Line! (1942) became the first Australian film to win an Oscar. There are many such “firsts” included in this chapter.

Ask Ganguly how he approached the chapter on Australian cinema, he says: “The approach was the same as for world cinema although I must confess, I had seen lesser of the serious Australian films lot than say Indian, American, or European films.”

“I loved The Story of the Kelly Gang when I saw it at a creative workshop. The criteria used for selection for the Australian cinema chapter was a mélange of facts from popular films and iconic films.”

George Miller for the win

Research and writing were a part of simultaneous process in this particular project, which took approximately a month for completion.

“Normally, it takes longer to write such a book but the sheer passion for cinema is what sailed the ship faster,” the author confessed.

When asked if there is any particular filmmaker who Ganguly thinks deserves more recognition based on his research for this book, he names American director David Lynch and Indian-origin Ritwik Ghatak and calls them both “underrated”.

Lynch’s films, he says, should be watched both for their dark humour and ominous tones as well as surreal cinematic style and amazing human relationships. Ghatak, on the other hand, was considered one of the three pillars of Indian world cinema but was eclipsed by another great director of Bengali films, Satyajit Ray.

The third director, who Ganguly feels, deserves more credit today is Australian George Miller.

“Miller is best known for his Mad Max franchise, which was one of the best action series ever. But Miller has also directed some other great films apart from the Mad Max series which deserve more recognition,” Ganguly shares. “Among them are Lorenzo’s Oil, The Witches of Eastwick, and the lovely animation films Babe: Pig in the City, and Happy Feet 2.”

Did you know?

The book interestingly mentions two anthropologists (Baldwin Spencer and Frances James (FJ) Gillen)) who captured footage of Aboriginal dancers in central Australia between 1900 and 1903 for some of the country’s earliest motion films. They invented wax cylinder sound recording and captured their films under challenging circumstances.

“This is something that I learnt from the records of National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA),” Swayam Ganguly shares. “The use of wax cylinders was one of the most interesting features of the early Australian cinematic history. These early recording devices used a large conical horn to collect the sound waves produced by humans and their musical instruments. The only problem was that these cylinders were short in length and could record for only a maximum of two minutes. There was no method to duplicate cylinders.”

Naturally, this technology was replaced by vinyl later. Spencer and Gillen’s wax cylinder recordings are now part of the British Library, Royal Geographical Society of South Australia and Museum Victoria.

The best part about Ganguly’s book is that it has the best of both worlds – serious cinema and entertainment-driven cinema.

“Just like a good Indian dish served with the best smattering of spices, this book has been written with a view to capture the imagination and interest of cinema lovers across the world. It aims to combine cinematic entertainment with cinematic knowledge most of all,” Ganguly explains.

READ ALSO: What Gandhi thought of Australia