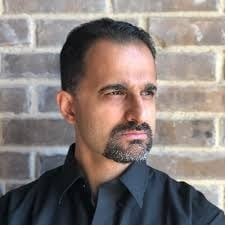

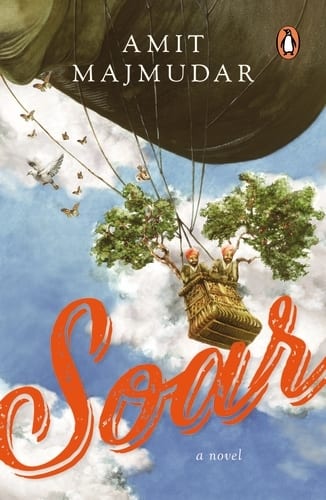

Conventional wisdom has it that there are bound to be differences when two communities live cheek-by-jowl in one country, but that these were exacerbated by the British colonial rulers to create a permanent divide before partition in 1947. To this extent, Penguin-Viking publication Soar by writer, translator, and nuclear radiologist Amit Majmudar, is a heart-warming tale of Hindu-Muslim bonhomie.

At its crux is a discussion between the two principal characters, Bholanath and Khudabaksh of the 1st Royal Gujaratis, as they recuperate in a cathedral converted into a hospital during World War I.

Is the God above looking the other way, wonders Bholanath.

“Oh no, he and Isu (Jesus) Crist and Isu Crist’s mother, Maryam – they are all watching,” Khudabaksh replies.

“Then they are letting Christians kill each other?”

“Don’t say that Bhola, what if some day, Hindus fall on Mussulmans and Mussulmans fall on Hindus?”

Bholanath laughed. “Why would such a thing happen? We have been living as neighbours for centuries.”

A little later in the discussion, Bholanath asserts that “you Mussulmans have nothing to fear from us Hindus”.

“You Hindus cannot rule the Mussulmans,” Khudabaksh maintains, “because the Mussulmans won’t have it”.

“Then what is the solution? Do we draw and line and say: Hindustan to this side, Mussalmanistan to the other,” asks Bholanath.

“That would be inconvenient for everyone, you would have to pack up all your clothes and couches, and hire coolies to carry them across.”

And still later, we see again:

“That’s only one of the problems with this idea. Once Hindus and Mussulmans are in two separate places, how will we go out on our feast day binges?”

“You won’t be there to sneak me in during Ramadan.”

“And you won’t be there to grab me extra almonds and a banana after the Hanuman puja.”

“Maybe Mussulmanistan wasn’t a wise idea after all.”

“Do you know what is a good idea?”

What?”

Khudabaksh smiled broadly. “Breakfast.”

In Majmudar’s Soar, Bholanath and Khudabaksh are assigned with their regiment to the Ypres Salient region of Belgium, where both lose their right hands in a grenade blast. Thereafter they volunteer as stretchers bearers, answering their commanding officer’s call for soldiers to man his observation balloon.

They are sent aloft on a gusty day. Disaster strikes with the tethering rope snapping and the balloon drifting off towards the German lines. The culprit is a squirrel that has chewed through the rope and thereafter settles into the basket carrying the two soldiers. The squirrel, christened Kabira in deference to the sensibilities of the duo, is quickly adopted, but the question arises: how is she to be fed?

Khudabaksh has the answer, tearing off pages from his pocket version of the holy book and suggesting Bholanath do the same with his holy book – “from now on, we alternate”.

What follows is a grand tragic-comic adventure, with the brothers-in-arms happily looking out for each other – even helping in the morning ablutions as they squat on the edge of the basket, supporting the other with their one good hand. The balloon takes them into the heavens, across a continent ravaged by war and even into the Atlantic, where they witness a cargo ship being torpedoed by a German U-boat till a change in wind direction brings them back to Europe and descent near the hospital.

In the process, Khudabaksh and Bholanath learn about the worst humankind can do and how true friends, whatever be their religion, can soar above it all.

Majumdar writes in a free-flowing style that gently grabs you by the collar and immerses you in the tale, sprinkled with wry humour. Sample this as Bholanath speculates, even as the balloon is over the Atlantic – he and Khudabaksh even prayed it would carry them on to Junagarh – that his mother would be mighty angry with him when he returns home.

“Why should she be angry,” asks Khudabaksh. “She’ll be happy to have her only son back, I’m sure of it.”

Bholanath raised his wrist stump. “This is going to make it difficult for her to find me a bride. I’m half as useful as I was before – and I was a good-for-nothing to begin with.”

Soar is a timely book for these troubled times.