The emotionally unavailable garden variety of commitment-phobic humans owe a huge debt to Sahir Ludhianvi. It is, after all, thanks to Sahir that they’ve found a poetic way of justifying their toxic behaviour patterns:

Taa-aruf rog ho jaaye toh us ko bhoolna behtar

Ta’aluq bojh bann jaaye toh us ko todna achchha

Woh afsaana jisey anjaam tak laana na ho mumkin

Usey ek khoobsoorat mod dekar chhodna achchha

Chalo ik baar phir se ajnabi ban jaayein hum dono

(If an acquaintance becomes an ailment, it is best forgotten

If a relationship becomes a burden, it is best broken

A story that cannot be taken to its logical conclusion

Is best given a beautiful tinge and then left alone

Come, let us be strangers once again).

The song, used in the BR Chopra 1963 directorial Gumrah, originally appeared as a nazm (poem) with the title “Khoobsoorat Mod” (A Beautiful Turn) in Sahir Ludhianvi’s debut poetry collection Talkhiyaan. First published in 1944, it became an overnight sensation. Many of the songs that we associate with Sahir’s lyrical prowess have their genesis in this poetry collection.

The enduring relevance of Sahir’s literary output has attracted poets, academics and literature lovers for decades. Contemporary Urdu poet Humaira Rahat penned a feminist response to Sahir’s “Khoobsoorat Mod”, asking the innocent yet piercing question in her nazm, “Kya Mohabbat Ik Pal Hai” (Is Love Just A Moment In Time):

Main dil se poochhti hoon

Kya mohabbat ko bhulaana

Is kadar aasaan hota hai

‘Chalo ik baar phir se ajnabi ban jaayein ham dono’

Bas is misrey ki ungli thaam kar

Barson puraana saath pal mein tod dete hain

(I ask my heart

Is it truly so easy to forget love…

‘Come, let us be strangers once again’

As if, by holding on to this one verse

You can forget those years of togetherness in just one moment).

From popular Hindi film songs to poems that have enthralled one and all, Sahir Ludhianvi’s literary output is vast, varied and worth investigating. It is a giant disservice to one of our foremost literary icons that whenever Sahir’s name is brought up in dinner table conversations, it’s mostly by virtue of his personal life and his doomed romance with Amrita Pritam.

So much ink has been spilled when it comes to the toxic relationship between Sahir and Amrita, that somewhere, it has eclipsed the need to talk about the nuances one finds in Sahir’s literary persona. It’s an unspoken tragedy that our impulse to needlessly romanticise this tragic and ultimately harmful relationship has resulted in Sahir’s literary output to be taken for granted. We are more interested in Sahir the person and because of it, Sahir the poet has suffered immensely.

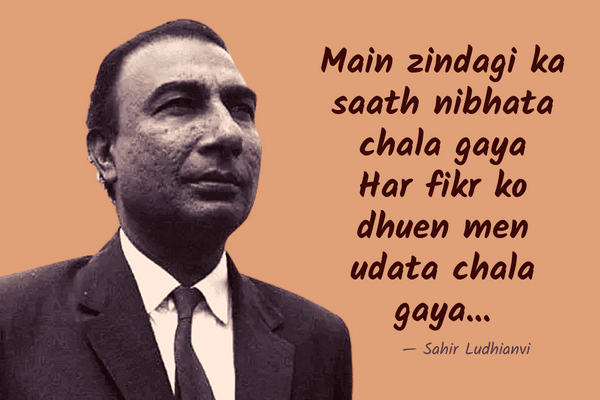

So, on his 102nd birthday, I want to rectify this situation. Let’s take a deep dive into Sahir’s literary world to discover what our “pal do pal ka shaayar” has to say about some of the most challenging issues that we’re currently facing.

Sahir Ludhianvi on Nationalism

Sahir was a staunch nationalist, but nationalism for him, much like his progressive counterparts, wasn’t an excuse to be subservient to the status quo and the regime of the day. It’s fundamentally odd and insidious how the implied meaning of nationalism has changed to imply that you are an uncritical and vociferous advocate of whichever regime is in power. Those who dissent are branded ‘anti-national’ today and criticism of the regime in power is conflated with working to conspire against the nation-state.

Going by this false dichotomy and twisted logic, Sahir would most definitely have been branded ‘anti-national’ if he was alive today. However, if we follow the classical definition of nationalism, he was very much a true nationalist, but was disillusioned with the policies of the state since India gained independence. The newly independent nation-state proved to be as oppressive as the displaced colonial powers, and for Sahir, this exercise meant exchanging one set of oppressors for another. In fact, one of Sahir’s most memorable songs from the 1957 film Pyaasa was a direct and rather unveiled attack on Nehruvian policies:

Zara mulk ke rahbaron ko bulaao

Ye kooche, ye galiyaan, ye manzar dikhaao

Jinhen naaz hai Hind par un ko laao

Jinhen naaz hai Hind par vo kahaan hain

(Pray, call the leaders of this country

Show them these lanes, these sights

Call upon those who are so proud of India

Where are they, those who claim to be proud of this land?)

Sahir’s nazm “Chhabees Janvary” (26 January) could very well have been written on the occasion of the Indian Republic Day earlier this year, instead of in his time period. The broader issues highlighted in the poem that are plaguing the nation, particularly around wealth inequality and the evils of communalism, remain remarkably similar despite the passage of time.

Daulat badhi to mulk mein iflaas kyon badha?

Khush-haali-e-avaam ke asbaab kya hue?

Jo apne saath saath chale koo-e-daar tak

Vo dost, vo raqeeb, vo ahbaab kya hue?

Har koocha shola-zaar hai har shahr qatl-gaah

Ekjahti-e-hayaat ke aadaab kya hue?

(If the wealth of the nation has increased, why this growing poverty?

What ever happened to the path towards ordinary peoples’ prosperity?

Those that had once walked with us towards the gallows

Where are those friends, those companions, those beloveds?

Every street is aflame, every city a killing field

Where did the etiquette of togetherness disappear?)

Perhaps, the clearest way to surmise Sahir Ludhianvi’s nationalist stance is through this verse, where he denounces all those who resort to hypernationalism and chestbeating levels of jingoism. For Sahir, it’s these hypocrites that go wherever the wind blows who are the true anti-nationals.

Hai jinhen sab se ziyaada daava-e-hubb-e-vatan

Aaj un ki vajah se hubb-e-vatan rusva to hai

(Those who make claims of patriotism the loudest

Today, it’s because of them that patriotism has been disgraced).

Sahir the atheist and rationalist against communalism

Aqaa’ed vahm hai mazhab khayaal-e-khaam hai saaqi

Azal se aql-e-insaan basta-e-auhaam hai saaqi

(Faith is but superstition, religion but a crude system

Human intellect has been held captive by these since eternity).

Many people are shocked to learn that Sahir Ludhianvi was an atheist and against all forms of organised religion, especially religious fundamentalism and orthodoxy. Perhaps, this is hard for them to imagine because some of Sahir’s most popular film songs are actually bhajans such as “Allah Tero Naam”. Many mistakingly assume that a person who is well versed in religious and cultural imagery must be a man of faith. This, of course, needn’t be true. In fact, a similar scenario emerges in the case of contemporary poet-lyricist Javed Akhtar, who is also a self-confessed atheist and yet, has written two of the most popular contemporary songs based around Ram Leela and Krishna Leela in “Pal Pal Hai Bhaari” from the 2004 film Swades and “Radha Kaise Na Jaley” from the 2001 film Lagaan respectively.

While you can find plenty of examples of Sahir’s leanings toward ilhaad (atheism) in his literary non-film poetry, the mainstream Hindi film medium seldom gave Sahir opportunities to express this side of his personality in film songs. Yet, if you pay close attention, the subtext is evident. For example, see this frothy, lilting melody from the 1965 Yash Chopra blockbuster film Waqt. On the surface, “Aage bhi jaane na tu” is a song that talks about living in the present. But equally, it can be read as an indictment against the claim that there is an afterlife. Once we’re dead, that’s it. There isn’t a Dante’s inferno or a cycle of rebirth to go through.

Is pal ke saaye mein, apna thikaana hai

Is pal ke aage hi, har shai fasaana hai

Kal kisne dekha hai, kal kisne jaana hai

Is pal se paayega jo tujhko paana hai

Jeene waale soch le yahi waqt hai kar le puri aarzoo

Aage bhi jaane na tu, peechhe bhi jaane na tu

Jo bhi hai bas yahi ik pal hain

(In the shadow of this moment, we all have an identity

In the presence of this moment, every entity becomes a story

Who has seen the future, who knows what might happen tomorrow

In this moment, you will get what you seek

Think, the time is now, fulfil what you desire

What lies ahead, you do not know, what is gone, you do not know

The only thing that matters is this very instant).

While his atheistic leanings were usually hidden in subtext in Hindi film songs, his hatred for the evils of communalism and sectarianism were evident in an overt fashion in his song lyrics. For yet another Yash Chopra film, Dhool Ka Phool from 1959, Sahir pens one of most piercing critiques of communalism conveyed through a song. A man addressing a young child sings:

Tu Hindu banega na Musalmaan banega

Insaan ki aulaad hai insaan banega

Achcha hai abhi tak tera kuchh naam nahin hai

Tujh ko kisi mazhab se koi kaam nahin hai

Jis ilm ne insaanon ko taqseem kiya hai

Us ilm ka tujh par koi ilzaam nahin hai

Tu amn ka aur sulha ka paighaam banega

Insaan ki aulaad hai insaan banega

(You will neither become a Hindu nor a Muslim

You are a child of humans, you will become a human being

It’s good that you don’t yet have a name

That you aren’t yet associated with any religion

That you aren’t accused of possessing that knowledge which keeps us divided

You will embody the message of peace and tolerance

You are a child of humans, you will become a human being).

Sahir: A vast, complex canvas to explore

Sahir Ludhianvi’s literary output is prodigious. It’s impossible to cover the sheer depth and variety that his pen has to offer, whether that’s his film lyrics or non-film literary poetry. There’s so much to uncover and I’ve barely scratched the surface. This is precisely what I mean. One of the biggest tragedies to have happened to our literary stalwarts is that even though they’re well known, the variety of their output isn’t. The more easily accessible thoughts, moods and feelings in songs – usually these are the softer romantic or tragic numbers – typically travel much further than poems or songs that have more challenging ideas.

Yes, “Abhi Na Jaao Chhod Kar” deserves endless replays until the end of time. It deserves it. But the next time you decide to swoon making googly eyes at Dev Anand (who wouldn’t?), take two seconds to discover what else came from the pen of the lyricist who wrote this immortal song. The answer might just surprise you.

Further reading: Anthems of Resistance; Sahir: The People’s Poet; Panchavi Hijarat

READ ALSO: Mir Taqi Mir, 300 years on