It was between 1943 and 1944 that India-Australia diplomatic exchanges were formally forged into a diplomatic relationship. Playing a key role in this, was Lieutenant General Sir Iven Mackay, Australia’s first High Commissioner in India. Mackay’s distinguished career as a soldier in the two World Wars, and as an educator between them, came in particularly handy in setting the foundation stones for an emerging relationship.

“Mackay’s rigorous education [in Cambridge] and his war experience [in the North African and Greek campaigns of the Second World War and afterwards], in particular dealing with politicians, gave him the skills required for the exacting task of being a first head of mission in a country like India which was undergoing profound change,” tells Eric Meadows, an honorary fellow in the Contemporary Histories Research Group at Deakin University.

The change Meadows is referring to is India’s Independence from the British regime in the same period.

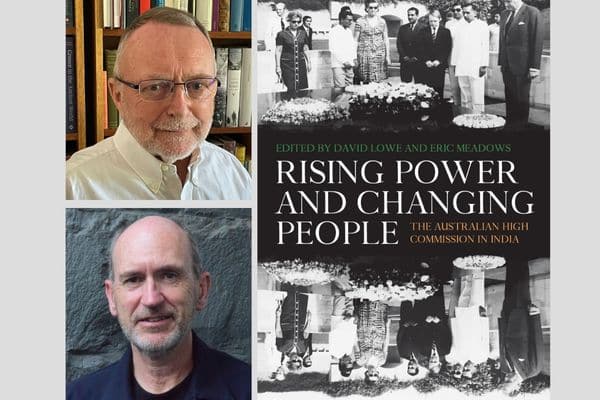

A new book titled Rising Power and Changing People: The Australian High Commission in India, discusses these early diplomatic exchanges between Australia and India. Published by the ANU Press, it is edited by Meadows and David Lowe, co-founder of the Australian Policy and History Network.

It was the British who initiated a relationship between India and Australia to assist India in developing its international diplomatic skills in the lead up to its Independence, Meadows mentions in the book.

“The major ‘dominions’ of the British Empire – Canada, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand – were asked to send representation. Australia was the first to respond and the creation of the High Commission [in New Delhi] in November 1943 was, surprisingly, India’s first formal relationship with another country,” Meadows tells Indian Link.

Mackay was an excellent choice as the first High Commissioner.

“His first task was the difficult one of establishing an Australian official presence in the rapidly changing environment of New Delhi,” Meadows adds. “India was rapidly approaching Independence but the Congress leaders were still imprisoned in early 1944. Once they were released, Mackay met Jawaharlal Nehru and kept up liaison with both the Congress and the departing British administration.”

After all, the Indian National Congress was the dominant political party in the country at that time.

Mackay’s successors

In post-Independent India, however, things began to unfold differently.

Mackay’s successor Roy Gollan was less suited to handle the diplomatic relations during the crucial period.

“Gollan had been posted in India in 1939 as a trade commissioner. His job was stimulating trading links between Australia and India, a task made difficult as WWII broke out,” Meadows mentions. “He was assigned to the staff of the High Commissioner once the post was created. For a period, he was based in Shimla while the remainder of the staff were in New Delhi. He had no responsibilities for political or military liaison or reporting to the Australian government on political issues of importance between the two countries.”

His appointment as the High Commissioner was a result of a dearth of suitably trained people to helm the diplomatic mission, the book notes.

Walter Crocker, on the other hand, was a great match unlike his predecessors – reflecting yet again the subtle influence of rising powers and changing people.

“Crocker had held a variety of positions in the British colonial service and in international organisations,” Meadows tells. “He understood the importance of building of relationships with key leaders; he developed an excellent working relationship with Nehru and other Indian leaders. He insisted on the highest standards from the staff of the High Commission – both in their personal lives as representatives of Australia and in the professionalism of their work and report writing. The standards he set have remained with the High Commission.”

Missed opportunities

Cut to 2022, both the nations share great trade and diplomatic relations. But is there potential unrealised and opportunities missed? Yes, maintains Lowe.

“One of the book’s main messages is that the relationship has endured a number of false starts, promising times that have not seen the relationship flourish as hoped,” Lowe explains.

For instance, immigration policy in Australia was not in favour of migrating Indians.

“Up to the 1960s, Australia missed the chance to remove some of the heat from its racially exclusive immigration policy, the so-called ‘White Australia policy’, by allowing a small quota of Indians to migrate. The Canadians had shown how this could be done; but domestic politics and a lack of courage made this too hard for the Australians,” Lowe adds.

Add to this the fact that Nehru and his counterpart Robert Menzies did not get along well as they should have.

“Neither did they try hard to find common ground in their encounters,” Lowe explains.

Nonetheless, some of the international shocks in the region helped both the governments better appreciate their shared interests.

“Two of these incidents that feature in the book are India’s war with China in 1962, and the bloody birth of Bangladesh in 1971. In both cases, the Australian government assisted India in ways that were swift and generous, and demonstrated a preparedness for independent and regionally sensitive foreign policy,” he adds.

From the 1970s, there were renewed efforts from both sides to realise the true potential of their friendship.

“But it was from the late 1980s when both countries began significant economic reforms and reorientations that the structural underpinnings for closer relations began to take shape. Thereafter, while there remained challenges, especially in relation to India’s nuclear testing, the increasing movement of goods and people provided a more robust basis for a closer, constantly developing relationship,” Lowe shares.

The future

So what are the untapped areas India and Australia could look at, to bolster this evolving relationship?

“At the end of the book, Peter Varghese, former High Commissioner and then Secretary of the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade DFAT, reflects that economic complementarities are becoming better understood [as the expansion of AusTrade offices in India attests], even if they are not being harnessed quickly,” Lowe tells Indian Link.

There are two other themes of mutual interest one of them being the changing strategic environment in the Indo Pacific region, resulting in the deepening of defence relations.

“The other is the thickening of ties that comes from people movement, especially India to Australia,” Lowe notes. “This includes not only temporary stayers such as Indian students, but the more permanent Indian diaspora settled in Australia which now numbers around quarter of a million, and is undisputedly the fastest growing. This people-to-people dimension of the relationship has great potential to hasten the identification of more opportunities in all realms of business, cultural exchange and otherwise.”

The book Rising Power and Changing People: The Australian High Commission in India is available and free to read here.