Saba Zaidi Abdi’s Adakar Theatre took to the stage at NIDA recently after a two-year pandemic-caused hiatus. It was with a double bill, no less – featuring Dozakh and Mughal Bachcha, both by Urdu writer Ismat Chughtai (1915-1991).

Chughtai’s core feminism formed a thematic link between both stories, and Saba’s deep understanding of Chughtai’s body of work allowed her to bring them to life beautifully.

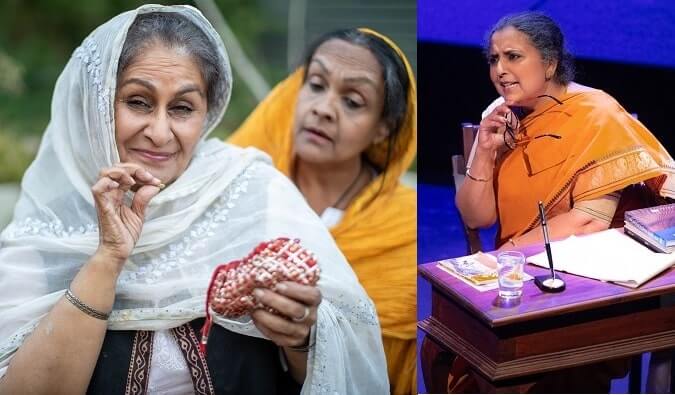

In Dozakh (Urdu for ‘hell’), Saba directed as well as starred as Naulas Khanum, one half of an odd couple compelled to share the twilight of their lives together. Opposite her was Bobby Suparna Mallick, playing Umdah Khanum. Was their abandonment – and forced partnership – a living hell, or were there elements of heaven in there for us to uncover? As they bickered away, often viciously, the true nature of their relationship became all too clear.

Saba’s advent on stage, returning home with the lota, was memorable, her laboured gait suggesting her advanced age brilliantly – you could almost hear her joints cracking. She impressed again as she made her paans with great passion, snored in her sleep, and traded hot gaalis with Umdah.

Bobby Mallick as Umdah translated brilliantly her desire for more from life. The incessant, energetic tidying up of her living space, and her readiness to fire back with a volley of insults, both brought out her fighting spirit.

In subtle ways, you gathered that one woman was reconciled to her old age, the other not so much – this yin and yang keeping their story alive.

And yet in that final crucial moment, when the realisation dawned that their life breath comes from nowhere else but from each other, one expected more from Saba and Bobby, the intensity tapering out somewhat when it was needed most.

READ ALSO: REVIEW: Black With Equal by Sydney’s Natak Mandali

Mughal Bachcha, set in the backdrop of a disintegrating Mughal Empire, unpacked the manner in which women suffer when society transitions into new realities. When males face a loss of power, the repercussions are felt by those on whom the frustrations are unleashed – women.

In the play Kale Miyan (Akshat Gupta) and Gori Bi (Zara Khan) prepare for their upcoming nuptials. The self-entitled Kale wants to hold on to the last remnants of a decadent society that is swiftly falling from grace, while the pure and innocent Gori Bi is blossoming in a transitional society which offers her more power over her own choices. The conflict on the wedding night changes Gori Bi’s life forever. Embracing a lifetime of solitude, she finds her solace in religion.

The errant groom returns years later, as if to seek atonement for his sins before his illness finally claims him. Whether there is a happy reunion or not is irrelevant – either way, it is a deeply sorrowful tale, and one that was able to touch the heart of the audience in quite a profound manner.

Chughtai herself made an appearance in Mughal Bachcha, in the form of actor Aparna Tijoriwala, the sutradhar (narrator). In clever experimentation with form, Chughtai’s story played out in the background, as she herself offered commentary in the foreground.

Aparna, dignified and measured as Ismat, further dignified her role with her wisdom-packed appraisals. Taking great care not to make them appear as judgements, she was able to wrest attention away from the protagonists Kale Miyan and Gori Bi, your glance squarely on her as the lights dimmed, distinguished in her writerly pose. It was as if the last hurrah was for Ismat Chughtai herself.

In many spheres of our own modern lives, there are social issues that continue to empower males disproportionately, with resounding repercussions on interpersonal relationships. Climate change and COVID are but two examples. Alluding to the contemporaneity of the works, despite the fact that they were written in the 1960s and were actually set at the turn of the century, Saba told Indian Link, “The women’s issues Chughtai wrote about, continue to be issues today.”

(And yet, some things have changed. Saba laughed as she recounted having to educate the younger actors about the entire concept of suhag raat.)

Both productions invoked a sense of time and place – the sets, costumes, and music each contributing impeccably to this end. The gali mohalla (street) feel in Dozakh came through appreciably. In the living quarters of the two roomies, one could easily have imagined one’s own grandparents fifty or so years ago.

In Mughal Bachcha, Gori Bi’s white-themed wardrobe struck the right chord. For the young Gori Bi, it symbolised purity and innocence, and the treasure that she was to her family. For the older Gori Bi, it stood for virtue and spirituality. Kale Miyan’s grand get-up did its bit to showcase his life in reflected glory.

Music was brought to play particularly effectively to create ambience, such as in the evocative Garam Hawa qawwali Maula Salim Chisti.

Language was authentic in its use – perhaps a bit too authentic for some in the audience, especially in those insults and counter-insults in Dozakh.

The anglicized Urdu by some of the younger cast grated at times, even as the older stars Aparna Tijoriwala and Bobby Mullick impressed with their speech (though both confessed to apprehension, being non-native speakers).

It was the three lead actors Saba, Bobby and Aparna that stood out, by far, in Dozakh and Mughal Bachcha. They have each stamped themselves in as leading members of our community’s stage scene. Having put in the hard yards to reach that position, we cannot wait to see the wonders they will bring to us in the future.

A final mention for Akshat Gupta, who was convincing as Kale Miyan – dark and unhappy in his frustration, aggressive in his physicality, cursing of his fate. He was everything Mughal in the dying days of the empire, and none of the finer qualities of its heyday – such as in the love of beauty and art and music and literature. All of that was in Gori Bi, his antithesis in more than name – forgiving and accepting, calm and composed, serene and graceful.

Together, in their own yin and yang, the two Mughal bachche stood for the extremes of their erstwhile empire – scaling the heights of beauty on one hand, and touching the depths of barbarism on the other.

If we remember one today, we must not forget the other.

READ ALSO: Manali Datar in Fangirls at the Sydney Opera House

Learn more about Adakar Theatre here