Poonam was the main one in her family in whom her mother confided. The stories started when Poonam was just a child; she thinks she was younger than her daughter is now. Most parents read books to their children before they sleep. Nirmal’s bedtime tales were of growing up in Lahore, the journey she made to India and the experience of being a refugee. She was not always judicious in the amount of detail she shared. Early on in her life, Poonam had a sense that something terrible had happened to her mother.

In the retelling of Nirmal’s experiences, it was as if she were reliving it all again. ‘It was part of our daily lives… It was the formative experience of her life and in a strange way it became the formative experience of my life because she spoke about it all the time.’ Poonam does not think of it on a day-to-day basis now, but says partition defined her because it so utterly defined her mother, and shaped who she became. ‘Partition is always there in the background.’

In the last years of her life, Nirmal lived in this family home, cared for by her daughter. Photos of her with her beloved grandchildren are on prominent display in the kitchen. Nirmal, or Nimmi as she was known, began her life on the outskirts of Lahore, born into a middle-class family in 1929. She spoke of her pets: the rabbits and dogs. Her family were Hindu, belonging to the Arya Samaj sect, which rejects idol worship and promotes equality of women. Theirs was a home full of music and singing. A twenty-year age gap existed between Nirmal’s parents. Her mother was married at the age of twelve, but was fortunate that her in-laws encouraged her ambitions to study. It was an unusual household, with Nirmal’s mother assuming the patriarchal role. She qualified as a teacher, and worked while her husband looked after Nirmal and her sisters.

Nirmal adored her father, who in turn doted on her. Like so many of her generation, she told Poonam of how she celebrated festivals with other neighbours, irrespective of religion, though when she was much younger at school she recalled an incident of a Muslim man knifing a Hindu bookbinder, which resulted in shops being closed in their area and panic spreading. Because of this, Nirmal was taken out of the Urdu section of her school and placed in the Hindi part. From time to time incidents like this did occur in her child – Nirmal pointed out – amongst both Hindu and Muslim fanatics.

Nirmal observed that hopes for independence from British rule were at first about desh prem, love of your homeland. But it soon became about love of your religion. The first inkling of this came when Ashraf, a Muslim classmate seated at her desk, punched the air with her fist saying: ‘We’re going to get rid of all of you… Lahore will be in Pakistan.’ Nirmal dismissed it, and thought it a strange comment from the girl, but Poonam identifies this as a significant moment.

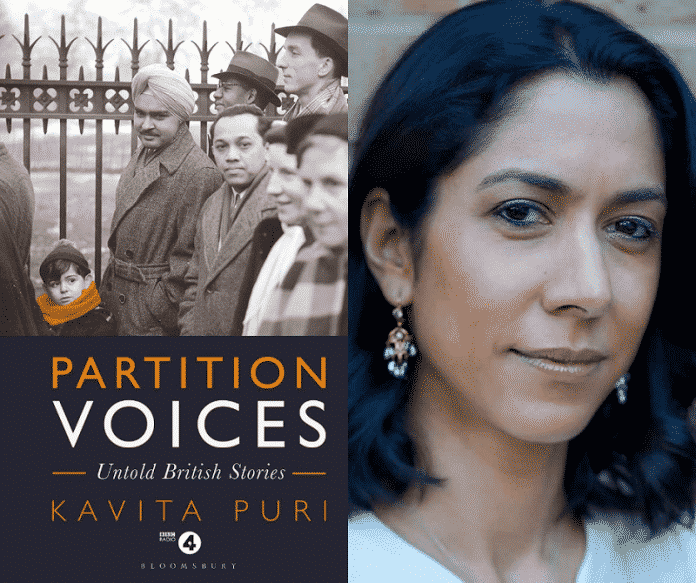

From Partition Voices: Untold British Stories by Kavita Puri (2019 Bloomsbury Publishing).

READ ALSO: The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company (Excerpt)

Link up with us!

Indian Link News website: Save our website as a bookmark

Indian Link E-Newsletter: Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter

Indian Link Newspaper: Click here to read our e-paper

Indian Link app: Download our app from Apple’s App Store or Google Play and subscribe to the alerts

Facebook: facebook.com/IndianLinkAustralia/

Twitter: @indian_link

Instagram: @indianlink

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/IndianLinkMediaGroup