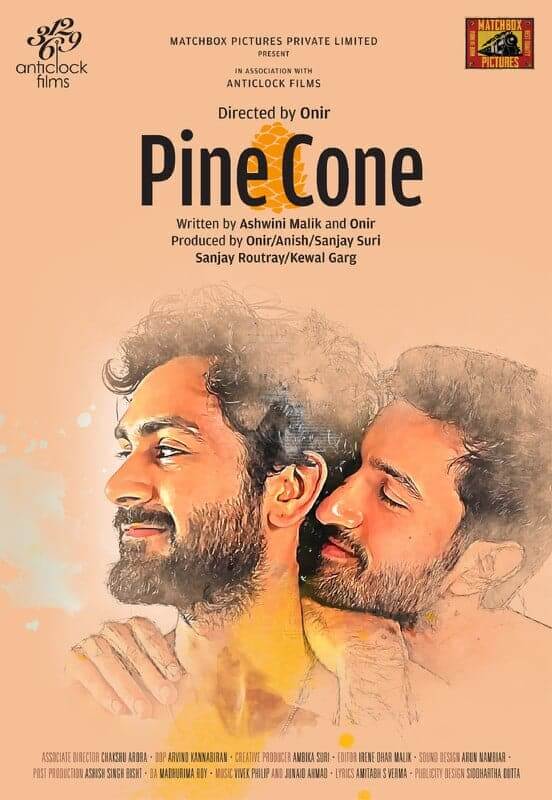

Celebrated filmmaker Onir recently travelled to Melbourne for the Australian premiere of his latest film Pine Cone at the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne 2023. We chatted with him about the process of making the film, and Indian cinema’s queer discourse after the 2018 verdict.

IL: Pine Cone is semi-autobiographical, but also takes place in three different time periods. How did you go about manifesting personal and political queer experience in this film?

Onir: I started off imagining myself as the characters, and then I worked with Ashwini Malik [co-writer] to get some distance from the script.

The film has a reverse timeline; I wanted the narrative to celebrate the [journey to the] 2018 Supreme Court verdict which decriminalised homosexuality and capture the changing landscape of the queer narrative in India. It starts in 2019, where Sid, a 38-year-old filmmaker is sceptical about love because of his life experiences. Then we go back to 2009, when the Delhi High Court decriminalised homosexuality. Sid is new in Bombay, navigating getting his stories told as a queer filmmaker and exploring himself in this city. Then it goes back to 1999, when he’s 18 and experiences love for the first time, and that’s the year the first gay pride happened in India.

IL: Part of your approach to filmmaking is creating a safe space. How did you do this during Pine Cone?

Onir: Casting was a challenge with the intimacy, a lot of actors refused. I wanted to celebrate queer desire, because if you see Indian films with queer narratives, it’s so sanitised or shown in a way where it’s all about lust. Love and desire are different experiences from lust, and I wanted to show that.

Obviously, you can’t ask an actor their sexuality, but I really wanted to cast queer actors. When Vidur who plays Sid said, ‘Onir, I’m queer’, that was such a beautiful discovery. I’m so glad my lead actor is out and proud, it made life easier in terms of comfort and shared experience.

I also love getting my actors to write backstories to their characters, and then put elements of that into the film, so it’s not just how I imagine the characters. For example, the paintings in the kitchen scenes are done by Vidur – that space becomes his and it makes him more comfortable.

IL: At the Q&A for Pine Cone in Melbourne, you talked about unapologetically showing queer desire. Can you tell me more about this?

Onir: I was kind of surprised when some people there said, ‘whoa, we were shocked’. It wasn’t meant to be shocking – it was just love, and I thought I showed it with beauty and tenderness.

Somehow the heteronormative world doesn’t want to consider queer desire. Recently, I was at this corporate talk about inclusion, and afterwards someone asked me ‘why do your community make it all about sex? Why can’t that be private?’

We’re the only culture to have looked at the science of sex or love, but still there is this constant pressure to stay in your bedroom and not be ‘in our face’.

IL: How do you feel the 2018 Supreme Court verdict has affected queer storytelling in India?

Onir: Obviously before 2018, it was difficult to tell queer stories because it was criminalised and censored. It’s good to see more openness now, but often it’s tokenism; when studios do something LGBTQI, it’s seen from the perspective of what works for a heteronormative gaze and what is ‘acceptable’.

There was a film called Badhaai Do (2022), where after dancing at pride, the queer characters at the end of the movie decide to be a straight couple. If that film portrayed it as a tragedy, I would understand, but it was shown as a ‘way out’, and for me that’s very problematic.

IL: How has the verdict changed your experience in the industry as a queer filmmaker?

Onir: As a [queer] person I’ve never felt discriminated, but I get discriminated against for the work I do.

I sometimes wonder, even after 2018, when studios are finally working on queer stories, why I’m not the one who’s doing it – why are straight men and women telling our stories? There’s still some sort of phobia which isn’t really being recognised.

When I went on stage for the [Rainbow Stories] award at IFFM and our trailer was being shown, there were industry people in the audience with shocked expressions on their face; there’s this whole thing of ‘Oh my god, maybe if we work with him, it’ll be another gay film, it’s too bold’.

View this post on Instagram

Even in a place of inclusion, they will make comments which are problematic. I feel that’s an overall reflection of the industry; as long as you are the ‘other’, it’s fine [for them].

IL: It feels like Indian cinema is behind the curve in terms of its discourse on LGBTQI issues, when in Hollywood, you’ve got films like Call Me By Your Name (2017) and Moonlight (2016) reaching the Oscars. Will we ever get to the stage of seeing nuanced queer discussions championed in Indian cinema?

Onir: I’m sure we will – Joyland (2022) was beautiful and came from the subcontinent.

Beautiful narratives are coming out of India, [especially] if you go to a festival like Kashish, but right now the support system is [limited]. If you go to a platform and pitch your story, they say ‘we’re already doing one gay film’, as though we have one homogeneous story, even though they’re doing 100 straight films. There are problems with how minorities in general are represented though, so I don’t think it’s only the queer community that’s singled out.

It’s a global problem; everything’s become about money…when people realise that the buying power of the queer community is large, then the entire tone will change too [in good and bad ways].

IL: The film came about when the Ministry of Defence rejected a script you were working on. With all the setbacks you face as a queer filmmaker, how do you keep going?

Onir: If it wasn’t a path I chose, then perhaps I’d be sitting and regretting; it was a conscious decision to tell a certain kind of story, so I can’t really complain. This is what gives me happiness.

Of course, there are times when you are frustrated or angry or sad, but I think overall your satisfaction and happiness outweighs this, and that’s why you keep doing it.

I feel one always finds a [way]; Iranian cinema, for example, keeps telling the stories they do in difficult [circumstances]. I feel hopeful, the world is opening up, and I see myself doing stories in other spaces.

READ ALSO: Stay in and watch these IFFM films