The rapid rise of China, India and other Asian countries in the last 50 years has prompted several writers to reimagine a world where Asia will be ascendant. A seminal work by Stewart Gordon, written in 2007, titled When Asia Was the World, was a reminder to the world – especially the West – that before the advent of colonialism and European empires, Asia was the centre of the world that beckoned Europeans. In the ‘dark ages’ when intellectual, cultural and commercial life stagnated in Europe, Asian societies were brimming with ideas, excelling in new scientific discoveries and spreading their religions far and wide. Gordon argued that Asia was simply reclaiming its position in the world stage today after 500 years.

Parag Khanna, in his new book The Future is Asian (2019) has argued something similar. Although for many in the world, the very mention of ‘Asia’ merely conjures up images of China, Khanna reminds us that Asia is a great deal bigger than just China, and encompasses everything from the Middle East to the Philippines, Indonesia to Korea. Although China has taken the lead in Asia, Africa and Latin America through its Belt and Road Initiative, Khanna argues it will not dominate Asia – or the world. While China is a major player in a broad Asian system, it is simply a feature of a highly prosperous Asian supercontinent now resurfacing on the world stage.

Be that as it may, China looms as the largest Asian giant today, its economy already the second largest in the world, and slated soon to become Number One in a decade or so. On a different tack, author Bertil Lintner in his thought provoking new book The Costliest Pearl (2019), highlights the struggle for supremacy in the Indian Ocean as the new Cold War, brought on by long-term Chinese strategy to replace the United States as the preeminent world power. China is using its economic power to gain a strategic foothold in the Indian Ocean with present or potential military bases that has been termed the ‘string of pearls’ – which has deeply unsettled India.

The costliest pearl that Xi wants is the Indian Ocean itself, and China’s re-entry into the Ocean after 600 years is part of its Belt and Road mega project – so much so that it has led to an informal ‘grand anti-Chinese alliance’ consisting of the US, India, Australia and Japan – and even France. So the future may be Asian; but there are some underlying and deep rivalries that cast a long shadow. What does it portend for intra-Asian interplay, particularly for China-India relations?

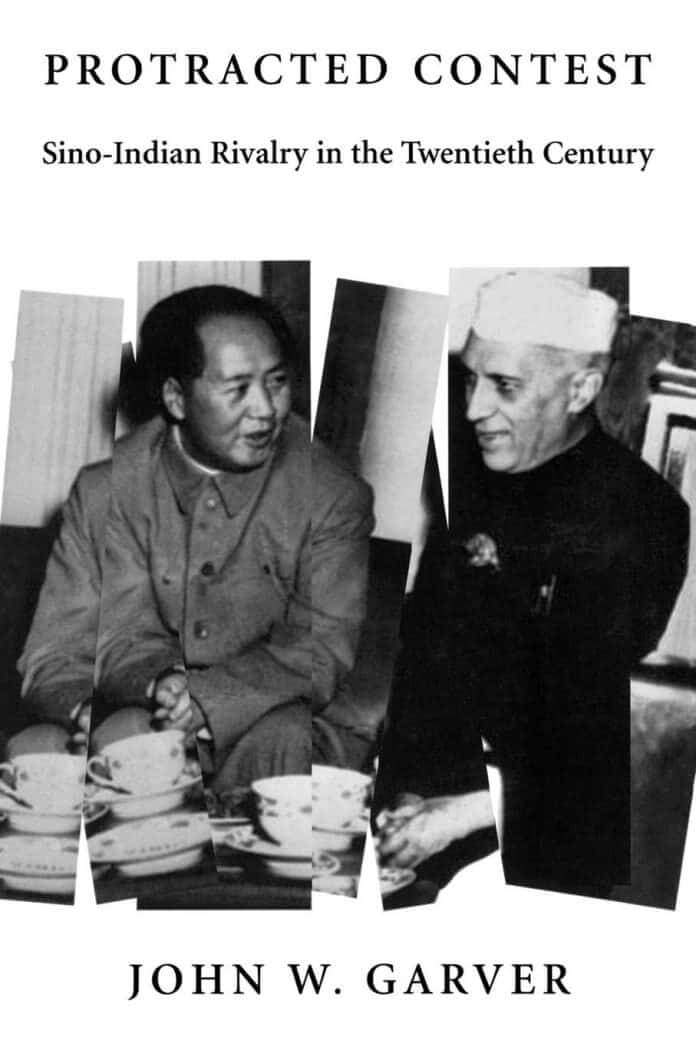

John Garver had predicted in 2001, in his book Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century, that China would be so dominant even in South Asia that India would have to acknowledge Chinese hegemony at some stage. Almost two decades on, the Chinese economy is 5 times the size of India’s, and China has assumed a swagger once seen in Imperial European and newly emerging economies: a kind of disdain for those who haven’t quite made the cut when they have done so. [One author has called it ‘Developmental Racism’ – an example was the sort of looking down on other Asians by the ‘Asian Tigers’ whose economies had ‘taken off’ in the 1980s].

Another new book that examines the China-India rivalry and is quite perspicacious in its assessment of where it’s headed, is Jeff Smith’s Cold Peace: China India Rivalry in the Twenty-First Century (2014). Jeff Smith observes that while Beijing and Delhi have spent the past half-century free from armed conflict and enjoy cordial diplomatic relations, elements of rivalry have cast a shadow on the relationship ever since the border war of 1962. In the twenty-first century, that rivalry has evolved in unpredictable ways, advancing in some arenas and retreating in the face of growing cooperation in others. Smith examines a whole swathe of rivalries and disputes bedevilling this relationship besides the border dispute: these include the Tibetan government in exile, their maritime relationship, Tawang, the role of the United States, Pakistan etc. Nevertheless, despite the two nations’ longest ongoing border talks since World War II, the author concurs with Indian and Chinese analysts that it is extremely difficult (nearly impossible) to resolve the border dispute in the short to medium term. Both Lintner and Smith have argued that increasing Chinese Navy (PLAN) presence in the Indian Ocean has triggered new confrontation between China and India. Smith makes it clear that it is ‘not a rivalry of equals’, and that ‘China can threaten India more than India can threaten China, which limits India’s ability to influence Chinese behaviour.’ How India manages this in the decades to come will be one of its greatest foreign policy challenges.