“Murder is a crime. Describing murder is not. Sex is not a crime. Describing sex is,” American cultural critic Gershon Legman said in 1949, decrying the official attitude that allowed cultural depictions of graphic violence but not sex.

As the 1960s began, however, two high-profile trials in the UK (‘The Lady Chatterley’ case) and the US saw rulings that sex in literary works could not be penalised on grounds of obscenity, and the erotic element became quite mainstream.

Sex has figured in literature, right from the ancient era, but saw a major fillip — and got differentiated from pornography — as the novel developed in the 18th century, with John Cleland’s ‘Fanny Hill’ (1748), or actually ‘Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure’, possibly being the first erotic novel.

The genre really hit its stride in the 20th century, as even established writers espoused it. ‘Josephine Mutzenbacher or The Story of a Viennese Whore, as Told by Herself’ (1906) was published anonymously, but is now attributed to Felix Salten, otherwise known for children’s classic ‘Bambi’.

Henry Miller’s ‘Tropic of Cancer’ (1934) and ‘Tropic of Capricorn’ (1939), Anais Nin’s ‘The Delta of Venus’ (from the 1940s, but published 1977), Pauline Reage’s ‘The Story of O’ (1954), Emmanuelle Arsan’s ‘Emmanuelle’ (1959), and Terry Southern’s spoof ‘Blue Movie’ (1970) are some notable ones.

Furthermore, sex scenes became common in other genres too — take Harold Robbins, Jackie Collins, and even in thrillers, say, Sidney Sheldon, Irving Wallace, the ‘Modesty Blaise’ series. A notable outlier was Alistair Maclean, who when asked about the absence of sex in his works, said it got in the way of the action.

READ ALSO: REVIEW: “Ganga’s Choice and Other Stories” by Vaasanthi

With society becoming more liberal (mostly) and new forms of media (OTT/online publishing) emerging, the trend has become common. As the success of ‘Sex in the City’, ’50 Shades of Gray’ and their ilk shows, the erotic in fiction, or even erotic fiction, no longer is seen as prurient, or as the preserve of dodgy publishers, or hidden away in bookstore corners (Indian readers of a certain generation would recall coming across Nancy Friday and ‘Letters to Penthouse’ and being chased away by bookshop owners/parents). And like other media (cinema/OTT especially), it no longer has to be apologetic, though challenges from “moral guardians” still persist.

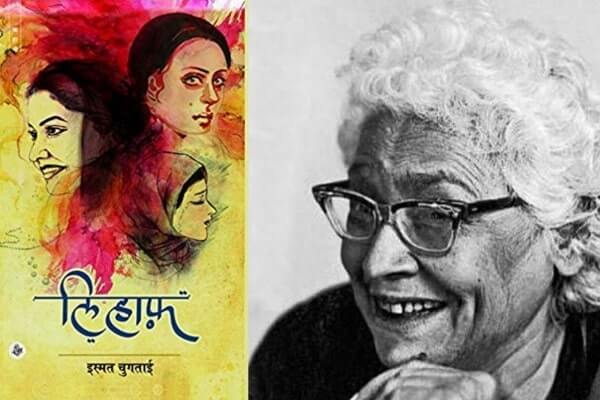

Indians had a long tradition of erotic literature down the ages. Let alone the ‘Kama Sutra’ or the ‘Ananga Ranga’, Kalidasa and his vivid descriptions (one about Shakuntala got the British translator all worked up), Jaydeva’s ‘Gita Govinda’ (though some deem it to be a religious allegory), Vallabhadeva’s ‘Subhashitavali’, Bihari’s ‘Satasai’, Telugu poetess Muddupalani’s ‘Radhika-santvanam’ (Appeasing Radhika), and many others show that our forebears were not shy about the topic.

Closer to our times, there were “bold” writers such Ismat Chughtai (‘Lihaaf’), Krishna Sobti, Khushwant Singh — never averse to pulling his punches on this count — and Shobhaa De. And now, authors don’t even need that label, as the range of anthologies, web stories, and the Indian imprint of the Mills & Boon series, apart from other works, shows.

Before listing some contemporary examples, it is important to note that the quality of the writing is important. (Many Indian-origin writers have been shortlisted for The Literary Review’s ‘Bad Sex in Fiction Award’, with two even claiming the dubious honour of winning).

Depiction of sex should “evoke a feeling and root for the character, not make it creepy, dirty, or derogatory to any gender,” says Madhuri Banerjee, whose oeuvre, relevant here, includes ‘Losing My Virginity And Other Dumb Ideas’ (2011), ‘Mistakes Like Love And Sex’ (2012), ‘Scandalous Housewives’ (2014) and ‘Forbidden Desires’ (2016) as well as the screenplay for ‘Hate Story 2’.

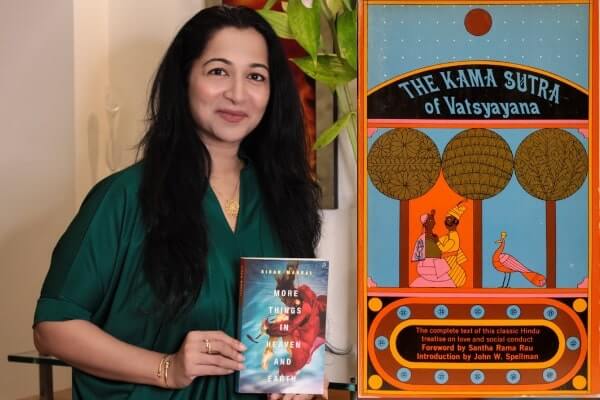

Kiran Manral’s versatile as well as prodigious output, spanning frothy romance (‘All Aboard’, 2015, and ‘Saving Maya’, 2108) to ‘Himalayan Noir’ (‘The Face at The Window’, 2016), to darker journeys into mental neverlands, as in ‘Missing Presumed Dead’ (2018) and ‘More Things in Heaven and Earth’ (2021), always qualifies on this score.

She says she is “generally not very explicit and detailed, I tend to leave a lot to the imagination. My aim is not to titillate but to put the reader in a scene, so they go with the moment.”

She notes: “One doesn’t really add a sex scene thinking, okay, let’s add a sex scene here. For me, the process is very organic, if the moment is progressing in a way that one needs to write it out so the reader will experience what the protagonist is going through, then one does so. If it would seem gratuitous, then I desist. I feel it is the characters who drive what I will write and it is they who tell me when they are going to have sex, and whether I need to write it out or merely allude to it and move on.”

Kiran also admits that “sex scenes are perhaps the most difficult scenes to write, after humour“.

Some others to see include Abha Dawesar’s ‘Babyji’ (2005), a coming-of-age story of a rather precocious teenage girl student in the early 1990s — a rather tumultuous time for the Indian youth, career and otherwise — as she explores her own sexuality and navigates complex relationships, including with her classmates and adults. Ananth’s ‘Play With Me’ (2014) may seem a fantasy but also provides food for thought on the intensity and durability of relationships, longing, and emotional support.

In short stories, Apurv Nagpal’s ‘Eighteen Plus: Bedtime Stories. For Grown-Ups’ (2013) uses various forms, including the transcript of a texting exchange, to explore sexuality in urban India. The uproarious ‘At the Big Fat Indian Wedding’ set in a resort where the bridegroom is having second thoughts and his friend has a series of encounters, stands out.

In ‘Eighteen Plus Duets’ (2016), Nagpal collaborates with 18 women writers to fashion another range of sex-themed stories, including ‘A Day of Desh Seva’ (along with Jo March), a satirical look at Indian politicians and bureaucrats in the course of a day.

‘A Pleasant Kind of Heavy and Other Erotic Stories’ (2013) by Aranyani also expands the genre’s scope, especially in its first story when a post-lunch massage leads to all sorts of things.

Then, two anthologies deserve mention — ‘Electric Feather: The Tranquebar Book Of Erotic Stories’ (edited by Ruchir Joshi) (2009) and ‘The Pleasure Principle: The Amaryllis Book of Erotic Stories’ (edited by G. Sampath; 2016).

There are many more, but it’s time to ask what do we make of sex in books?

Just passing it off as a way to titillate readers, the literary equivalent of the Bollywood “item song”, would not be very valid, for it does provide insights into emotions, personal and gender relations, social mores, and norms, the state of society itself — and desires and aspirations.

While for Kiran, making her female protagonists sexually active “has been this need to show agency and female desire”, Madhuri says: “I write about women empowerment. And one facet of that empowerment is sexual liberation. I add a scene when the character has a desire and has been denied or repressed for a long time as I did in ‘Scandalous Housewives’ (2014), where each character was scorned for some reason but found happiness in a new way.”

That we can relate to.

IANS

READ ALSO: Book Review: ‘Ritu weds Chandni’ by Ameya Narvankar