Ajay Navaria’s characters shun stereotypes, topple hierarchies and reclaim their rights

I cannot decide whether bracketing Ajay Navaria as a Dalit author completely defeats the power and purpose of his prose in the first place. Because he is not just a Dalit author but, like all writers, a social commentator of his time as well. However, not calling him that, is also denying the psyche of his characters and the setting of his stories, and falling prey to the practice of selective understanding and documentation of literary voices from oppressed communities.

In the history of Dalit characters, what sets Navaria’s writing apart is that his protagonists are not merely helpless and skewed portrayals as seen in the works of non-Dalit authors like Munshi Premchand, or more recently Manu Joseph in his Serious Men. Novelist Shashi Deshpande said of Joseph, “Making a Dalit man speak in English and making it authentic is very difficult – but Manu Joseph has done it very easily, without making it grotesque.” The comment is as patronising as Munshi Premchand’s portrayal of Dalit characters, and continues the tradition of empathy and passive suffering for these characters and humiliating monikers such as harijans, completely overlooking the various nuances of caste politics and the Dalit movements of the time that were aimed at battling these very stereotypes.

Then, does that mean non-Dalit authors should be barred from portraying Dalits? No. But as K. Satyanarayana, an authority on Dalit Studies, notes, “Despite their serious commitment, non-Dalit writers miss the dreams, desires and visions of Dalits and objectify them as either victims or romanticise them as great people.”

And it is in this context that the contribution of writers like Navaria to the body of Dalit literature, and to sensitise the likes of Premchand, Joseph and the rest of us about a world we pretend to understand (and regularly stereotype), but do not really comprehend, becomes important.

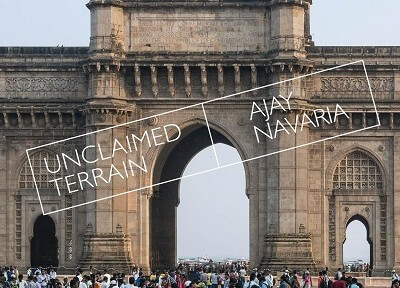

In his Unclaimed Terrain (published in India by Navayana and translated into English by Laura Brueck and released by Giramondo Publishing in Australia), Navaria’s protagonists are grey, full of flaws and insecurities but, at the same time, have the internal agency and resources to emancipate themselves.

Unlike the first wave of Hindi Dalit writers in the ‘90s who focused on relaying their suffering (dard-bayan), Navaria is not afraid of confrontation with the elite classes. “In their writings, the emphasis was more on bhav (emotion) than bhasha (language/artifice). Their experience was their identity. Their writing was communitarian – the story of one person became the story of the community,” he says.

Navaria’s language on the other hand is angry and passionate. In ‘Sacrifice’, a tale of father and son, where to his father’s indignation the son changes his name to shed his caste identity, and comes to terms with his father’s trials involving an affair with a Brahmin girl, he writes “to be born weak is a mistake but to remain weak is a crime”.

His non-Dalit characters too are human and hence flawed, but not beyond redemption. And it is here, in his humane portrayal of non-Dalits, that Navaria completely reverses the equation (earlier, only writers from elite castes usually wrote about Dalits with limited imagination and understanding) and bravely enters an unclaimed terrain. In ‘Yes Sir’, this reversal is clearly visible when a Dalit untouchable is attended to by a Brahmin peon named Tiwari, who is later seen cleaning the untouchable’s clogged bathroom drain. Navaria hints at the inherent nature of our societal structures that maintain hierarchy – where someone orders, someone serves, in this case a reverse hierarchy, which Tiwari blames on kaliyug to the readers’ amusement.

In the book’s preface co-founder of Navayana, S. Anand writes, “Every name is a parade of imagined history, the announcement of privilege or the lack of it, and emits a radioactive signal called caste.” Caste, on the other hand, is not etched on one’s skin, and needs some speculation. In ‘New Custom’, a dapper Dalit passes for a darbar (a suffix meant for elite landlords) till his true identity is discovered and he is put in his place by a tea-stall owner and a smirking Gandhiji from a 100 rupee note. The sneaky yet skillful allusion to Gandhi and his problematic stance with respect to caste inequalities shows Navaria’s cunning in his craft.

The author was in Melbourne in April this year to participate in Literary Commons!, a unique conference convened by Mridula Nath Chakraborty in an attempt to engage Dalit and Indian tribal writers with Indigenous Australian writers. At the conference, Navaria spoke in favour of the anonymity experienced by Dalits in the city, which allowed some freedom and acceptance as opposed to villages, where the structures were more stagnant. The story ‘Subcontinent’ examines these two structures closely and the plight of the protagonist caught in between the two, while ‘Tattoo’ deals with the anxieties of a middle-aged bureaucrat who drops his surname to hide his Dalit identity, which ironically has been branded into his consciousness in the form of a Jai Bhim tattoo, like most of Navaria’s male characters who carry a little bit of Ambedkar in them.

Navaria’s response to Premchand’s hapless portrayal of Dalit characters can be found in ‘Hello Premchand’, where he rebuilds the possibilities for these characters and empowers them. Mangal, the scavenger-boy in Premchand’s ‘Doodh Ka Daam’, an IAS officer in Navaria’s portrayal, is emboldened by his peers.

He creates controversial protagonists like the one in ‘Scream’ who leaves for the city to start a new life and becomes a masseur-gigolo, whose very profession makes him break caste rules every day.

Navaria’s Dalit is not a caste; rather it is a symbol of new beginnings and revolution, capable of showing the light at the end of the tunnel to the Rohith Vemulas of India.

“The value of a man was reduced to his immediate identity and nearest possibility. To a vote. To a number. To a thing. Never was a man treated as a mind. As a glorious thing made up of star dust. In every field, in studies, in streets, in politics, and in dying and living,” wrote Rohith in his parting note.

Writers like Navaria have an important part to play in giving courage and conviction to the young Rohiths of India who have lost faith in the system.