Sydney actor Suparna (Bobby) Mallick was in the audience at Bangalore when playwright Mahesh Dattani first presented his play Twinkle Tara in 1990. Little did she know the profound impact it would have on her.

32 years later, Mallick has just finished her third presentation of the play, now famously renamed Tara. This time round, she was directing, after having been part of the cast in 1999 and again in 2010.

It’s almost as if character Chandan’s words, ‘Nothing ever changes… except the date’, were written for her.

Mahesh Dattani’s Tara is about grave social ills that refuse to be obliterated from Indian society. For our women, real life is far removed from the goddess and mother archetypes that dominate our rituals and fill our art and literature. Inequalities and bias continue to define our lives, often even before it begins.

The favouring of male children and female infanticide are the basic tenets of this disturbing play, but they are seen at the intersection of a host of other factors, equally grim.

“The many layers in the text drew me to it,” Mallick told Indian Link. “It’s not just about gender bias – it’s about patriarchy, about domestic violence, about the way our society has dealt with certain things.”

The “certain things” in the play, particularly, are deep family secrets that are driving a wedge in the Patel family. Son Chandan (Rwik Chatterjee ) and daughter Tara (Dhanvi Dave) are young adults who started life as conjoined twins, their clinical separation causing them to lose a leg each; dad (Rushi Dave) is controlling and has plans for the son but not the daughter, and mum (Rima Sen) is near neurotic in her care of the frail daughter. Outside connections are limited.

The first Act painstakingly sets this scenario up for us.

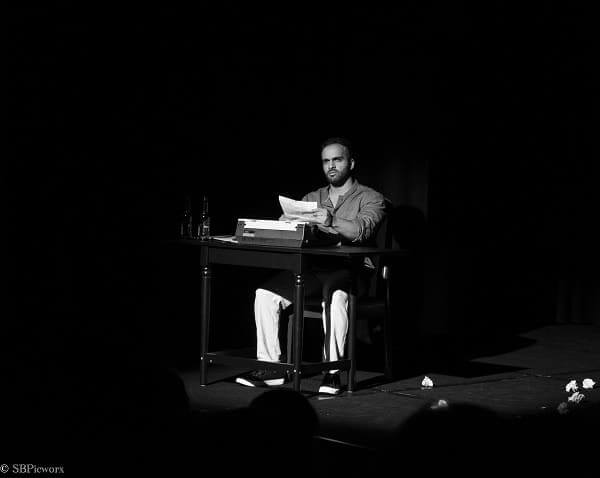

Dan, the adult Chandan (Shaunak Mallick) is struggling as a writer, not going past the title and date on his manuscript as he limps between his desk and the liquor cabinet in unending despair.

On a lower level of the stage, his memories play out to tell us the cause of his misery.

As a young lad, his father’s patriarchal attitude causes him to rebel and shrink inside a world of writing and classical music. Tara’s rapidly failing health is inverse to her mother’s care attempts. A nosy young neighbour is observing it all. The marital discord between the parents increases unabated under the weight of some dreadful secret, until a frenzied moment when the mother collapses in a fit of hysterical screaming.

At the very end of Act 1, this disturbing scene leaves the audience shaken to their core.

On a higher podium on the stage sits the doctor, in his grandiose suit and swivel chair, recounting the surgical separation he performed on the twins years ago – god-like, or more appropriately CEO-like.

READ ALSO: Review: Ruchi Sanghi’s Anarkali The Musical

Act 2 was equally if not more intense, and deeply chilling in its resolution. The real story of course is told here: it turns out, the female twin had full chances of survival, but the family chose otherwise – convincing the doctor with a suitable professional bequest.

The reveal of this shameful secret is intended to put the complex family dynamics into perspective, but the unspeakable injustice of it all punches you in the face. And gnaws at you for hours after.

It is for Act 2 that the performers were bracing to show their mettle. The torment for each played out differently.

Shounak Mallick as Dan was convincing: having to single-handedly carry the burden of his family’s unpalatable truth for the rest of his life, he communicated his turmoil and utter, wretched helplessness brilliantly.

Rushi Dave as Mr Patel was the quintessential dad – he who will carry on providing, making the best of what he has been dealt in life.

Rima Sen’s hysterics as Mrs Patel, undoubtedly a bit extreme, served their purpose in highlighting the family’s joint anguish.

Ananya Dixit as Roopa the pesky neighbour brought in much-needed moments of light relief in an otherwise intense play. Perfectly cast, the audience clearly took a fancy to her, even though her one-dimensional role was perhaps the easiest to play.

Rwik Chatterjee as the young Chandan did his best to exude a precocious wisdom and acceptance, but he was the most convincing in the rare moments when he clashed with his father, setting the stage for the adult Chandan to be open about the disdain in the filial relationship.

Dhanvi Dave as Tara had the most difficult role of all. Multifaceted in its burden, it required her to be playful with her brother, dreamy about her own future, dutiful towards her father, respectful of her mother, stoic in the face of ridicule on the streets, warm towards a girlfriend and then bravely dismissive of her as her deceit came to the fore, helpless in her own bodily pain, traumatised when caught between warring parents trading loud insults.

Her performance ultimately did balance the competing demands placed on Tara, although a greater chemistry between her and Chandan, being necessary, went somewhat amiss.

READ ALSO: Are we a tolerant society?

Interestingly, Mallick chose cleverly to have her characters retain their original accents, and so we identified Kannada, Gujarati, Tamil and Australian intonations in language, in what turned out to be a wonderful microcosm of the community we live in.

In terms of sets, the split levels on stage are classic Dattani: here they might well reflect the base-level Ego, a hidden lower-level (or unconscious) Id, and a seemingly moralistic higher-up Superego, to use Freudian terminology.

Together, each element in this production did its bit to expose our flawed attitudes towards gender issues, as well as our troubled attitudes regarding disability, middle class morality, science without morality, and an unnecessary competition to keep up with the west.

If the intent was for you to leave the theatre with a sense of anguish, then this production did it remarkably well.

READ ALSO: REVIEW: Kannagi Enbathen Peyare by Samskriti Dance