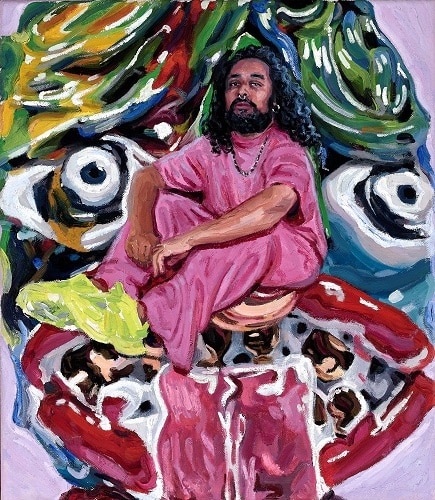

Ramesh Nithiyendran sits, in Kirthana Selvaraj’s Archibald Prize portrait, engulfed in colour.

The strong splashes suggest such intense energy that you almost step back to take it all in.

Your eyes dart between the two large eyeballs on either side, and finally settle in on the main figure – which is covered head to toe in more colour.

In the midst of all this bustle, the look on the face – is one of quietude.

“Ramesh is known for the boldness of his personality,” Kirthana told Indian Link. “Yet I’ve come to know of him as an introvert, a profound thinker. My first portrait of him was in his public image, but this second one, I’ve based on his personality.”

Kirthana Selvaraj first met fellow artist Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran – recognised for his daring, colour-rich and genre-busting sculptures – at university.

“I’ve admired him since seeing him at UNSW where I was studying and he was teaching,” she recounted. “I loved how he dressed, getting a unique cheerful vibe off him. Then I followed his work and connected with it – he was from Western Sydney, Tamil like me, making work that acknowledges culture and heritage, challenging notions that South Asia is a monolith. I chose him as my Archibald subject for a multitude of reasons: I respect him as an artist, and like him as a person.”

The portrait became a tribute not only to his guiding influence, but also to his body of work.

“In his own work he puts disembodied parts of himself into his sculptures,” Kirthana described. “So I decided to present him sitting on the face of one of his sculptures, as a way of honouring his style of work.”

She describes in her artist’s statement that this also “references his neo-expressionist compositions and nods to the Hindu mythology of vahana, meaning ‘that which carries, that which pulls’”.

Ramesh himself is no stranger at the Archibald, having been hung five times, three times as a sitter and twice with self-portraits.

Yet he admitted, “Being a sitter can be anxiety provoking… particularly as you offer your face to another person. But I’m selective about this process. The Archibald is special – one of the only art situations that achieves national attention. There is great opportunity to engage audiences.”

Interestingly, this year’s event began as a kind of therapy for Kirthana Selvaraj, as she inadvertently turned to Ramesh Nithiyendran during a low period.

“I was a finalist for the Lester Prize at the Art Gallery of WA, and the couriers lost my painting. It was ultimately found, but after judging had taken place. It was devastating. The only way I knew to get over the feeling was to paint.”

She brought out the studies she had sketched after meeting Ramesh at his studio.

It is not surprising then that this work – her second Archibald hanging – is gratifying in many ways.

“Not only is the piece compositionally different, the process was different too,” Kirthana said, looking back. “It is quite abstracted – there are no smooth transitions; it is not blended but separated, because I want you to be able to see the hand of the artist, and the potential of paint. Get up close, and notice the choices and decisions I make in the work. In the shoes for example, there are only three to four brushstrokes. I want people to notice that, and acknowledge the intentions behind the brushstrokes.”

And yet, contrastingly, there’s a high degree of realism in the face itself. Perhaps this comes from her early pull towards portraiture.

“I’ve always been curious about people and faces, noticing nuances that other people perhaps don’t,” Kirthana admitted. “At art school, there was a push against figurative work and towards more experimental work and new mediums, but I’ve felt pulled back to body and face. I suppose it reflects a yearning for connection, having perhaps been lonely as teenager. But more than a way of connecting with the social world around me, I observe what people do with their faces, how they express or mask emotion, how they connect with others. There’s so much data you can extract from a face.”

Kirthana’s penchant for placing her subjects within an elliptical halo of sorts, is brought to play again here.

“Yes I do like that threshold space, that in-betweenness, of walking through an archway,” Kirthana offered. “It speaks of potential, of the unknown… In this case the figure could be thought of as situated politically, entering the unknown space of brown people painting brown people. Not sure if this is the first time this has happened at the Archibald, but it’s certainly the first time a Tamil person has painted a Tamil person!”

As a brown artist, Ramesh Nithiyendran may be prolific at the Archibald, but he is a recent entrant himself at the 102-year-old event.

“It’s amazing to see a critical mass of artists from the South Asian diaspora developing in Australia,” he observed. “We have layered, complex and interesting stories which have emerged from culture, migration, tradition, and subversion. These narratives are now engaging various audiences.”

Indeed, in the past few years, we’ve been pleasantly surprised to see artists as well as sitters from South Asia, in what is a slow but sure opening up to new influences.

“I don’t believe first and second generation south Asian migrants were particularly encouraging for their children to pursue arts education,” Ramesh mused. “Art education was perceived as unreliable or mystifying in terms of career and stability outcomes. (This) generation, seeing themselves reflected in these spaces, feel confident to pursue unconventional paths in the context of their communities.”

And what was it like for Kirthana to have Ramesh sit for her?

“Of course I was nervous,” Kirthana Selvaraj laughed. “He’s well known and respected. He did connect with a pivotal part of the process though – he said at one stage, put your pen down, you’ve said what you wanted to say. He acknowledged the final product was how he saw our friendship.”

READ ALSO: Kirthana Selvaraj in her ‘green suit‘ at the Archibald