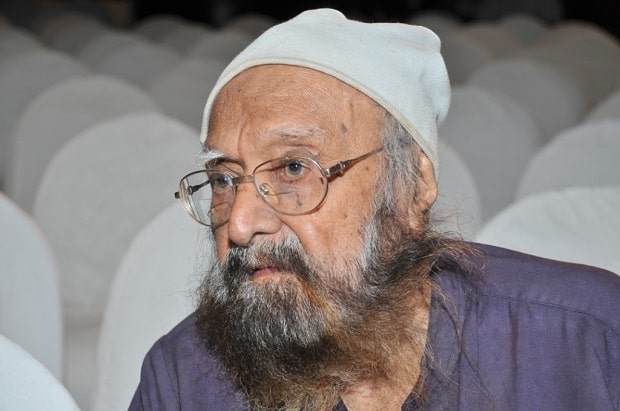

Minus Malice: Grand old lord of fine print

March 20, 2014

“All that I hope for is that when death comes to me, it comes swiftly, without much pain, like fading away in sound slumber. Till then I’ll keep working and living each day as it comes,” Khushwant Singh wrote in the book Absolute Khushwant: The Low-Down on Life, Death and Most Things In-Between in 2010. His wish was realised.

Singh, who died on Thursday at the age of 99, had a long, successful and – most colourful – career.

Bursting on the literary firmament with a collection of short stories, The Mark of Vishnu and Other Stories in 1950 and his partition novel, Train to Pakistan in 1956. He followed it up with The Voice of God and Other Stories, The Sikhs Today, Ghadar 1915: India’s First Armed Revolution, Delhi: A Novel, and The Sunset Club.

His last book, The Good, The Bad and The Ridiculous, was published in October 2013.

A household name among English language readers, Khushwant Singh reached out to millions every week with his column, “With Malice Towards One and All” – a post-mortem of current affairs, reviews, critiques, opinions and a punchline. Humour was his trademark and a wicked candour resonant with satire and a sort of cynicism set his writing apart from the rest of his Indian peers.

Two events, the partition of the country and the 1984 riots, cast an indelible impression on his writing. The siege of the Golden Temple in Amritsar by the Indian Army in 1987 prompted him to return the Padma Bhushan which was awarded to him in 1974.

The man with words in his blood was born to Sobha Singh, a prominent builder in Lutyen’s Delhi Feb 2, 1915. He went to Modern School in the capital and subsequently to the Government College in Lahore and to King’s College in London before studying for the bar at Inner Temple.

“I was meant to be a lawyer, but I got a job as a diplomat (he worked as press attache at the Indian High Commission in London). I found it very boring and then I started writing. My first collection of short stories was published in London … and I threw up my job. Anyhow I started writing books, got little money. Then came the break,” he recalled several times walking down the memory lane for friends and media.

Writing gave him sustenance.

“I decided upon a three word formula – inform, amuse and provoke … With provoke, I found that anytime I write something about people, they took me to court,” he often said.

Warm, sharp, analytical and compassionate, Khushwant Singh, in his later years, was hard of hearing, a fact he was sometime embarrassed of. But he never failed to exercise his intellect – almost daily – by writing.

“It was a regimen that he followed religiously,” recalled a close associate.

Singh was often labelled as “dirty old man of Indo-Anglian writing” for his brazen references to sexuality and lewd humour. Beautiful and cerebral women stirred the connoisseur in him – like the fine liquor he was fond of sipping throughout his life.

“Love fades, lust lasts,” he once admitted in a lighter vein in an interview.

In a biographical documentary, Not a Nice Man to Know. But a Good One, old associates like Vikram Seth, Mani Shankar Aiyar, editor Nandini Mehra, cook Chandan and typist Lacchman Das described him as a man with “youthful spirit, candour, wit, honesty and 20 cats”.

His humane and honest self spilled over into his books as well. The opening paragraphs of his Train to Pakistan says, “The fact is, both sides killed”.

The book, which was inspired by his return to India from Lahore where he practised as a lawyer before partition, recreates the horror of partition.

His sixth and last novel The Sunset Club was yet another example of the man, who had initially supported the state of emergency clamped by then prime minister Indira Gandhi, and then became her vocal opponent.

In his later years, he was concerned by the growth of fundamentalism in India and wrote out against all forms of extremist and nationalist religion that militated against India’s secular ethos.

“I am 96 … I think I should now learn to do nothing. I owe it to myself. Besides, when I am not doing anything … it keeps me relaxed … I must tell myself that my life is almost over,” Singh had said in an interview after the publication of The Sunset Club, a tale of three old men and the lives they had lived.

But he went on to live three more years, writing his occasional columns, reading a lot, keeping himself abreast of the daily news, imbibing his ‘chhota peg’ and, as Rahul Singh, his son and a former editor of Khaleej Times, said, leading “a great life, (in which) he touched the stars and he touched our careers”.

“Not many in life are fortunate to get the cards he was dealt and he played the game to victory. Immensely hard working, dramatically well-read and very private, Khushwant Singh laughed at the solitary reaper and must have told him a sexy joke when he knocked on the door,” summed up Bikram Vohra, editorial director of London’s Asian Lite magazine, who worked with him in the Illustrated Weekly in Mumbai. He said: “You cannot mourn a man who lived life to the full and did it on his own terms”.

IANS