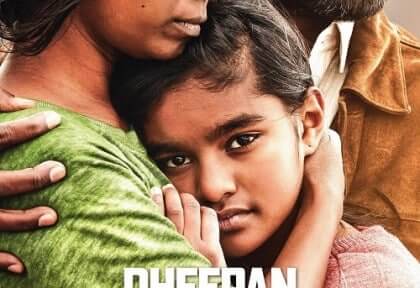

APARNA ANANTHUNI reviews Jacques Audiard’s award-winning Dheepan, which screened at the Human Rights Arts & Film Festival in Melbourne in May 2017

“Now you are this family.” Acclaimed filmmaker Jacques Audiard’s award-winning Dheepan promises a complex and charged story, as three survivors of the war against the Tamil Tigers – a man, a woman, and a nine-year-old girl – claim the passports of a dead family, escape Sri Lanka by boat and attempt to build a new life for themselves in France. And the film does indeed explore the slow, grim struggle to rebuild your life from your identity upwards, as well as the way war shapes human resilience.

In Dheepan, the little ‘family’ escapes war only to find themselves caught up in another war, the drug war that brews in the neighbourhood they are resettled in. Former Tamil Tiger soldier Sivadhasan, now named Dheepan (Antonythasan Jesuthasan) is the main protagonist, embodying the full gamut of being a refugee, a migrant, and a survivor of war scarred by violence and loss. “Sometimes they say things and laugh. I understand all the words. But I don’t find it funny,” he says of his new French friends to his ‘wife’, who is now called Yalini (Kalieaswari Srinivasan).

Dheepan captures the power of the little things, as the characters build a new story and life for themselves – Yalini’s delight in recognising the dog that lives with the old infirm man she has to cook and clean for, Dheepan shutting his photo of his dead wife and children behind little handmade gold doors, and Illayaal, now their ‘daughter’ (Claudine Vinasithamby), singing a song in halting, newly learned French.

But there is a deeply disturbing flaw at the centre of this film: the unacknowledged intersectionality of Yalini’s plight as both a refugee and a woman. Although she freely initiates a sexual relationship with Dheepan, the camera has already previously objectified her body through Dheepan’s gaze, as he watches her naked in the bathroom without her knowledge.

This frame unintentionally foreshadows what is to come: his physical and verbal violence towards her when she tries to leave France, terrified by the drug dealers they are both working for, and his unwanted sexual advances to her after their fight, made several times despite her clear “No’s”.

The film tries to force us to make excuses for Sivadhasan / Dheepan, and sympathise with him – in much the same way he forces Yalini, through a combination of abuse and emotional blackmail, to do what he wants, to forgive him, even as he puts all their lives in danger.

The film ends with them living happily in England together, with Illayaal and a new baby, and to cap it all, the last shot we see is of Yalini’s hand stroking Dheepan’s hair comfortingly. The film tells repulsive lies about domestic violence: that he didn’t mean it, that it was because of the war, that it can all go away once he leaves the bad things behind. It tells us that women don’t verbalise trauma like men do.

It tells us that violence against women is normal for a man like Dheepan. Perhaps the title says it all: this is a film about a man, filled mostly with men, about what war does or can do to a man. Most tellingly of all, Dheepan is the only character who has an original name – we never find out what Yalini and Illayaal were called before they left Sri Lanka, who they used to be, or what traumas they are trying to flee.

This camera’s gaze is male. The male gaze trumps female personhood, swinging away from Yalini and Illayaal to focus obsessively on Dheepan and his internal battles. And the male gaze’s violence and destruction goes unaddressed.