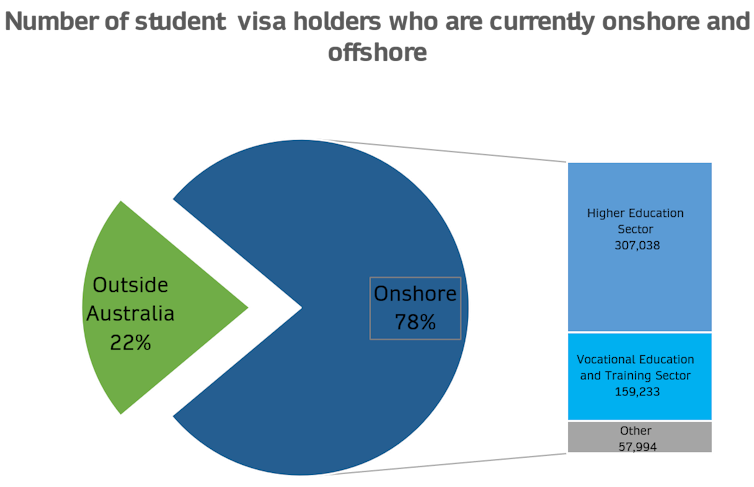

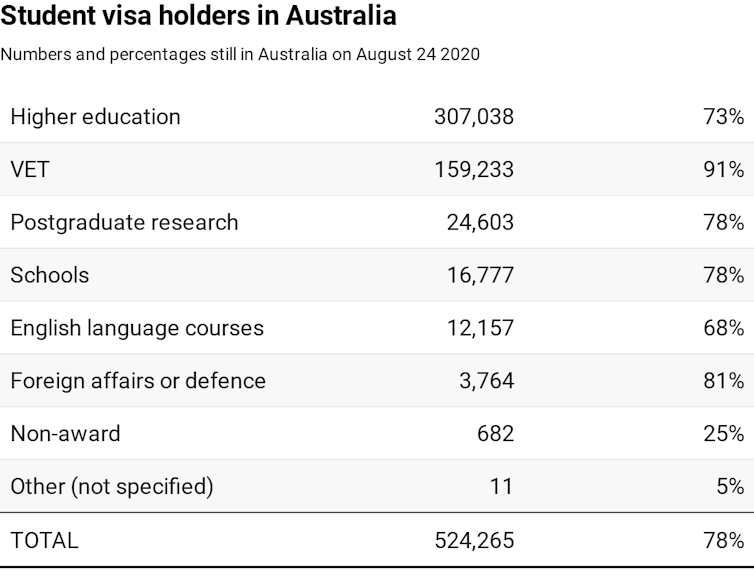

COVID-19 has not stopped international education. As of August 24, 524,000 international students were living among us in Australian cities and communities. They represent 78% of all student visa holders, according to data the Department of Home Affairs provided to us.

These students are potential ambassadors for Australia and our institutions. They could help shape our country’s reputation as a safe and welcoming destination in the post-pandemic world – but only if we look after them.

The numbers of students now in Australia vary across sectors. Currently, 73% of our international higher education students and 78% of postgraduate research students are here. The vast majority — 78% — of our international secondary school students are still here too.

The percentage is even higher for vocational education and training (VET): 91% of the sector’s international students are here, 159,233 in all.

Non-award programs (shorter courses that don’t lead to a degree or diploma) and English language programs (ELICOS) have the largest percentages of students now offshore.

The experiences these large numbers of students are having now will have a direct impact on their decisions and patterns of mobility once borders reopen.

However, institutions and government agencies continue to focus on outward-looking approaches to recovery, such as offshore recruitment and delivery, negotiating pilot safety corridors, and scenario planning for the reopening of borders. The onshore response to international education risks being severely neglected.

Read more: Sanjay Alapakkam: Law Student of the Year

Students are comparing countries’ responses

International students in Australian cities and communities are of course talking about their situation. They are using social media, creating blogs and interacting constantly with families and friends back home and around the world.

During the pandemic, this peer-to-peer form of marketing is heightened in its global reach. Our students are constantly comparing their lives with students in both their home countries and Australia’s major competitor destinations.

As a result, the crisis of international student social support is the subject of global comparisons. Students and their families are weighing up what they are going through “here” compared to what others are going through “there”.

Read more: RMIT Indian Club supports Melb students with free groceries

A life transformed in Melbourne

Arya is a full-time postgraduate student from India who is staying in Melbourne. We spoke with Arya as a part of a series of interviews with international students during COVID-19.

Her dream of studying in Australia was made possible through a combination of a student loan, borrowing from family, and savings after working for two years as a journalist. Prior to COVID-19, she relied on part-time jobs to support herself. This income was essential to her financial survival in Melbourne.

The first lockdown meant she lost both her jobs — one in hospitality and one at her university. As these sectors are struggling in this crisis, her prospect of finding a new job is bleak.

Arya is not eligible for federal government support such as JobSeeker. But she might be able to get Victorian government support, including a voucher to buy groceries and a one-off payment of A$1,100. She can also apply for a modest grant from her university to cover some bills.

She has struggled to pay rent, but the moratorium on evictions has prevented her from becoming homeless. Her university and local community groups in Melbourne have also provided food hampers.

Arya’s goal was to study in Australia at a world-class institution and solidify her status within the upwardly mobile middle classes in India. Her life has been transformed into a struggle to eat, pay rent and avoid homelessness while keeping her grades up. Arya observes: “It is becoming more than an education. The question is shifting to how students live and survive in a global city midst a pandemic.”

Read more: Visa changes for international students

It’s even harder in the US

Arya is in contact with friends and fellow Indian students studying overseas. While her situation in Melbourne is dire, her friends in the US are struggling every day. Arya introduced us to Dhanya.

Dhanya, who moved to New York in 2017 to study, says she is struggling “despite doing everything right”. After recently graduating and finding a job, Dhanya lost her H1B sponsored visa for skilled workers as a result of the Trump administration’s recent freeze on visas. “The US government has not considered that we can’t get home,” Dhanya says.

She reports that she and many of her friends in similar situations have been told they can choose to work as unpaid interns.

Many American states enacted a patchwork of temporary eviction moratoriums and the federal government issued a partial ban on evictions. These moratoriums have now largely expired, forcing students to rely on the discretion of landlords. As a non-citizen, Dhanya cannot receive unemployment benefits or a stimulus cheque.

Dhanya is unaware of any non-monetary support from her university or the government for international students. There are no free meal plans, grocery vouchers, or community-based food schemes.

Despite our Melbourne-based student living with the daily anxiety about her finances, she is comparing her experience relatively positively to her friends in the US.

Some countries are enhancing reputations

Students are paying attention to countries that are including international students and temporary migrants in their social policy response to COVID-19. Arya says: “The way countries handle this now is definitely going to impact how students see your country as a destination in the future.”

Arya and her friends are keeping a keen eye on European destinations such as Germany and Sweden. They have also been impressed by Canada’s timely support for international students during this crisis.

Read more: How COVID may impact the future emotional lives of students

It is not enough for Australia to rely on other nations doing badly on social welfare and support. We need to do more than aim to receive a comparatively “good” score on poverty, exploitation and vulnerability based on others doing worse.

Australia urgently needs to actively reshape international education market perceptions by demonstrating that we offer not only world-class education but also world-class student support. And that starts with helping the cohort of more than half-a-million international students who currently call Australia home.

Angela Lehmann is an Honorary Lecturer at College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

Aasha Sriram is a Research Assistant at Melbourne Social Equity Institute, University of Melbourne

This story was first published in The Conversation. Read the original here.