Three human tragedies, one war, one genocide, and a partition, led to the birth of a lasting love story between two artists, Indian-born Kiron Sinha and Austrian-born Gertrude Hirsch.

The 72-year union left a rich legacy in its wake, which the Adelaide-based Verna Blewett and her daughter Lily Hirsch, social scientists and researchers, are trying to capture in a catalogue and a book.

A promise to capture – and preserve – artist Kiron’s creations, started their journey. It has taken them to Australia, parts of India, Chennai, Kolkata and Delhi, to trace lost and dispersed art works.

How the artist couple met, and found an anchor in each other, is quite fascinating.

Gertrude lived in Vienna in the 1930s. Her family were of Jewish origin, and uncomfortable with the rise of the Nazis, probably realised they would have to leave. After completing her Diploma in Fine Arts with top marks at the Vienna University in 1936, Gertrude’s interest in theosophy led her to Theosophical Society where she met then-President George Arundale and his wife Rukmini Devi. “They offered her an art teacher job in Kalakshetra School in Chennai, paid for her passage, and she left on a boat in 1937,” Verna recounts to Indian Link.

Her brother Leopold moved to Australia in 1938. “He tried convincing their parents, but they refused. They didn’t survive the Holocaust (1941-45), and died in Theresienstadt,” says Verna.

Verna’s late husband Robert Hirsch was Leopold’s son.

Ironically, at about the time Gertrude was travelling to India, Kiron Sinha himself was on a boat, escaping from China which was hit by the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-45). He had been studying in Nanjing University after securing a scholarship, post his Diploma in Fine Arts from Kala Bhavana, Visva Bharati.

“It was a premiere university for arts at the time, we suspect it was granted by Nandalal Bose (a leading figure in modern Indian art). Those records no longer exist, as their early records have gone missing,” Verna reveals.

They met at Kalakshetra. Kiron taught the older children, and Gertrude, the younger ones. “There were a lot of men sniffing around her, Kironda said, which I thought was un-Indian,” Verna chuckles. “She was very beautiful, tiny, frail-built, slender, gorgeous woman. He was gorgeous himself: tall, dark, handsome. They married in 1938.”

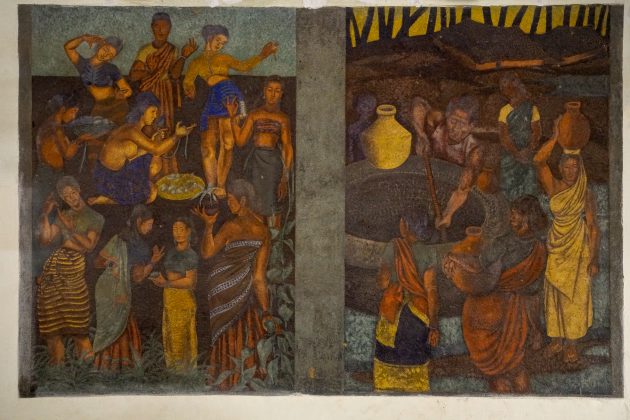

The pair stayed put in Chennai for around seven years. “I know they were there in 1942, as they had painted two large murals on the walls of Women’s Christian College, which still exist, and I was able to photograph earlier this year,” says Verna. “He went to Mahabalipuram, perhaps alone, and had a look at the fabulous caves and monuments. I also did, they influenced his paintings, the women in large breasts and curvy forms.”

Gertrude melded her life into his completely, taught him anatomy and composition, and was the subject of his work. He made sculptures dedicated to her. “She dropped her art career for him. She used to say to me, look, I am an Indian woman, and so, I support my husband. She got the jobs, and he painted full-time,” recalls Verna. “They had a daughter in 1945, Kamona, Bulbul for short. Bulbul Studio, which later became Bulbul Art Gallery, was named after her. Unfortunately she died in an accident, in 1972. I can see different styles in his work – before her death, and after.”

“Kironda always described himself as born under Saturn, his life was a life of loss, which was sadly true. It was like the loss of the Holocaust had met the loss of Partition. He lost his family: his mother died when he was 12, his father perished during Partition, his sister died as a child, his brother later. They lost their land, and finally their daughter,” she shares.

The couple was caught in the cross-fire of India-Pakistan partition in 1947 as they had moved to Lahore by then. “He left his paintings behind, and she also lost her possessions. That is the only place we couldn’t get to, where they spent a significant time. He had to escape since he was Hindu and got the last train out from Lahore in 1947, with two-year-old Bulbul. Gertrude followed them later.”

After returning, they built a home and settled in Santiniketan, near Kolkata, living there from late 1940s until their deaths – Kiron in 2009, at 95, and Gertrude in 2011, at just over a 100.

By this time, Indira Gandhi, likely his classmate from Santiniketan, became his patron, and developed a friendship with Gertrude. “I have handwritten letters to them from Indira Gandhi. She also bought paintings as PM, gifting them to foreign dignitaries and diplomats, which I’d love to find,” she says. “They even stayed with her during an exhibition in Delhi. Two of his paintings are in the reception room at Nehru Museum.”

There was regular correspondence between the Hirsch families: Leo, his wife Gerda and their son Robert wrote letters to the couple. In 1963, Gertrude visited her brother with Bulbul and held exhibitions of Kironda’s work in Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney.

“Robert was 13. Many paintings were sold, we are keen to find them,” says Verna, who also wrote them letters, as a new entrant to the family.

“We married in 1986, I am from a boring Anglo-Celtic background,” she laughs. “In 1988, Robert visited them in India, meeting Kironda for the first time. Kiron wanted his artwork introduced to an audience outside India. He felt he had been ignored, partly true, as he wouldn’t play the art game, or promote himself, and expected people to touch his feet. He knew he was brilliant, and was, but didn’t want to put in work towards recognition.”

“A difficult man, he had a wonderful sense of humour and was very intense about his artwork. If there was a surface, he just covered it with some form of decoration. He painted what was around him, influenced by European masters, like Rembrandt, and his use of light,” observes Verna. “You can see that in many of his paintings: the colours were completely foreign palettes for the time and for an Indian artist. The influence lost points for him in the early days with Nandalal Bose, who was pushing local, and there was some conflict there.”

Verna herself didn’t meet Kironda and Gertrude until 2007. “I saw his gallery, and murals he had painted on his wall, sculptures in the garden, and was just gobsmacked, overwhelmed with the beauty that was there. I realised there were no records of this wonderful legacy. I asked if he would let me do this and he said yes. I am doing this to help him get the recognition he deserves, as promised,” she says.

The mother and daughter have been visiting India every year since, spending time, recording conversations, photographing, researching for the catalogue and book, except in the year 2015 when Robert died. Verna has made this her retirement career now since Lily has started her own.

“It is a huge task. I had hoped to have an outline for the book ready, but the catalogue took time, as I was consulting. We’ve captured over 700 records – of his paintings, sculptures, designed ceramics, murals, frescoes, block-printed fabrics. It will be released this year, and housed on our website and with the International Federation for Art Research in New York, as a catalogue raisonné,” says Verna.

“Their life is worth documenting, with the intersection of Holocaust and Partition – and the place their paintings played in the development of Indian art. Mukul Dey wrote about him as an artist who introduced new palettes, his style was so exceptional and different. Amazingly, we have found support from all quarters. It’s been a story served by serendipitous events.”