India and Hong Kong share a common British colonial history. From the earliest times that connection and free enterprise attracted many Indian merchants to migrate to the “barren rock” where they prospered and became some of the city’s most prominent businessmen and philanthropists.

Whatever their colonial shortcomings, the British brought a system of democratic government, the rule of law and free enterprise. Whereas India has just celebrated 75 years of independence from British rule, Hong Kong had to wait until 1997. Under an historic “One Country, Two Systems” agreement with China, the city was guaranteed its distinct political, socioeconomic, and legal arrangements for at least fifty years without change.

While India has gone on to stamp its presence on the world as a vibrant, democratic, growth economy, once free, Hong Kong has succumbed to Beijing’s imperious interference in its domestic affairs. As liberty’s light is extinguished, so goes the city’s renowned international financial centre’s future.

But China’s President Xi Jinping won’t fret. He is contemptuous of individual liberty, market economies and what he can’t control. He seeks to replace lost international business with domestic demand. With total debt of 290 percent of GDP, falling productivity and weak profitability, it is wishful thinking. Beijing’s options are shrinking and its future is not what Xi tells the world.

Seven decades of communism have cemented a corrupt ruling class built on cronyism and nepotism. Xi Jinping is a product of that system. Some 70,000 heavily subsidised zombie companies sap productivity. Investment and divestment rely on patronage, not profit, and previously concealed bad debts threaten the viability of financial institutions. China is no longer the cheap manufacturer it was and President Xi’s obsession for control, means a “please Beijing” culture crowds out risk taking and innovation.

Most crippling is Mao Zedong’s legacy of the one child policy. Despite efforts to up the quota to three children, China is currently experiencing its lowest birthrate since the 1950s. It means in coming decades over 100 million workers will retire with no-one to replace them. China’s over 60s population is already at 17.9 percent compared to India’s eight percent.

READ ALSO: The Pegasus spyware saga reveals India’s colonial hangover

When compared to India, China’s future looks grim. With its young, smart, energetic population of 1.4 billion people, untroubled by totalitarian leadership, India stands as a beacon to global corporations looking to reposition. Indeed, according to research firm Gartner, a third of supply chain leaders have plans to move at least some of their manufacturing out of China before 2023 and up to 1,000 companies have India under consideration.

No doubt this reality accounts for Beijing’s flagrant incursions into disputed territories. It sees time running out and wants to deter the West from defending Taiwan should it attack.

It’s true, until recently, China’s miracle economy has mesmerised the world. But Beijing got a ten year start on Delhi thanks to Deng Xiao Ping’s 1980s reforms. It wasn’t until 1991 when a collapsing Soviet Union convinced the Indian Congress to abandon socialism that India’s star began to rise. Only then did it begin ditching the economic rigidities and entrenched patronage common to socialist regimes.

The changes included privatisation of government assets and a concerted effort to deregulate mainstream sectors. Indeed, India is keen to dispel its old image of stifling bureaucracies aware that smaller government means less corruption, lower transaction costs higher returns and increased investment. Unlike China, ownership is a two-way street with very few sectors requiring prior central government approval for foreign investment. Limits on foreign direct investment across key industries have been increased.

Today, India is a land of emerging opportunities with a growing appetite for a diverse range of high value services and products. It has reached a new level of growth and maturity without surrendering its competitiveness. For 2021-22 the International Monetary Fund forecasts India’s GDP will grow by 9.5 percent, well ahead of China’s 5.7 percent.

These profound developments are serendipitous for Australia, particularly at this time. While many in government and business may yearn for a rekindled relationship with China, it won’t happen under Xi. Canberra’s decision to deny Huawei participation in its 5G network and its push for an investigation into the origin of COVID-19, angered him deeply. Now,with America’s abject retreat from Afghanistan, Xi’s wolf warrior diplomacy in Asia and the Pacific will put further strains on the relationship.

In this context, India has become an indispensable security partner for Australia. Both are members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue which also includes the United States and Japan. Its aim is to support “a free, open and inclusive Indo-Pacific Region” and, to China’s chagrin, its members have established regular defence co-operation through naval exercises, and the sharing of intelligence.

Five years ago, a compelling opportunity pushed by Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi and then Prime Minister Tony Abbott, to complete a comprehensive economic co-operation agreement, was inexplicably squandered by Abbott’s successor Malcolm Turnbull. Now, as Australia’s special trade envoy, Mr Abbott is endeavouring to re-boot this bilateral agreement. It follows an understanding between Prime Ministers Morrison and Modi to “re-engage” and upgrade their relationship to a comprehensive strategic partnership.

To give this effect, the Prime Minister and the Minister for Trade need to inject a fresh sense of purpose. It means Australian bureaucrats must urgently find common ground. Too often they have created obstacles or concentrated on non-negotiable issues rather than find solutions. To build momentum and, as a measure of good faith, Mr Morrison should visit Delhi before year-end or, at least, meet Mr Modi at the margins of the Glasgow climate conference in November.

The Indian train is leaving the station and unless Australia moves quickly, it risks losing its place in a lengthening queue. To quote Mahatma Gandhi, “The future depends on what we do in the present”.

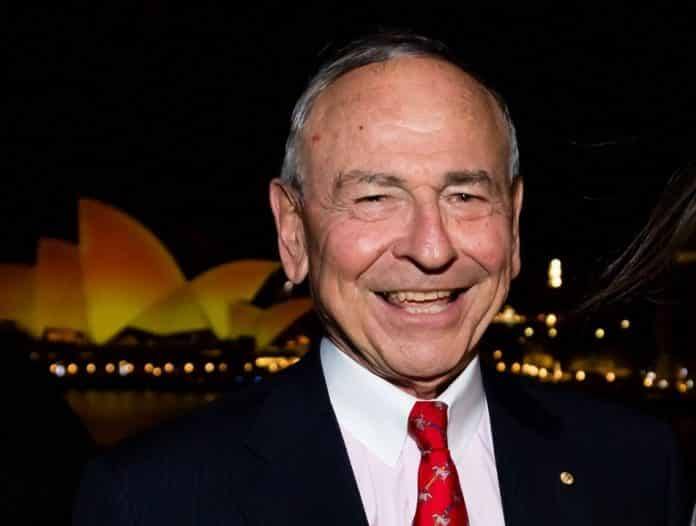

Maurice Newman AC is a former Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) Chairperson and has also served as Chancellor at Macquarie University.

Reproduced with permission from The Daily Telegraph.

READ ALSO: Indian-origin journo wins Pulitzer for exposing China’s detention camps

Link up with us!

Indian Link News website: Save our website as a bookmark

Indian Link E-Newsletter: Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter

Indian Link Newspaper: Click here to read our e-paper

Indian Link app: Download our app from Apple’s App Store or Google Play and subscribe to the alerts

Facebook: facebook.com/IndianLinkAustralia

Twitter: @indian_link

Instagram: @indianlink

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/IndianLinkMediaGroup