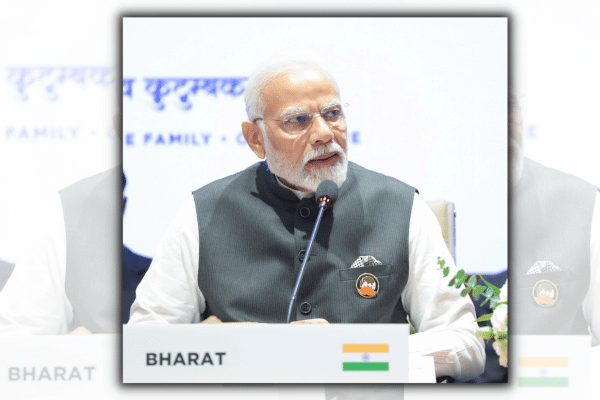

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi took his compatriots by surprise with his country name plate at the recently concluded G20 summit in New Delhi.

There had been heightened chatter about a possible name change in the days immediately preceding, but most thought it was just that – an idea that would probably come under discussion, perhaps in the upcoming special session of Parliament convened on Sept 18.

And yet we had Droupadi Murmu being described as the ‘President of Bharat’, and the Prime Minister displaying the name ‘Bharat’ on his desk at work at the international event.

No amendment to the Constitution, or two-thirds majority in Parliament, or a referendum (which India has never seen).

Yet there hasn’t exactly been a massive hue and cry, simply because the term Bharat is one we are deeply familiar with, one that is in use on a daily basis domestically. It appears in our Constitution to describe ourselves as a nation, and on our passports to stamp our national identity. In essence, it is the Hindi word for India, as ‘Bharatiya’ is the Hindi term for ‘Indian’.

The revert to the Hindi name (Sanskrit would be ‘Bharatam’) is seen as a dismantling of the influence of historic invading forces that changed our homeland – whether European in 1700-1800, or centuries before that, by Persian powers.

Enough discussion has now ensued to conclude that the enduring name India is not colonial baggage, but in fact precedes colonisation.

“Hindu” is the Persian version of Sindhu, the civilization-building river that the Achaemenid Persians had to cross to get to modern day South Asia.

And “Bharat” of course is a term that precedes even that, finding reference in the Rig Veda (literally, ‘The Knowledge of Verses’, the oldest known Hindu text dated circa 1500–1000 BCE). The Bharatas were one of the foremost kingdoms of the land, their name coming from Bharat, the illustrious son of Shakuntala and Duhsyant, predecessors of the Pandavas and Kauravas of the epic Mahabharata.

Regardless of the fact that the India of today is no longer the same as the Bharat of the young prince Bharata, just as for example the France of today is no longer the same as Gaul of centuries ago, the name Bharat invokes an original ideal, a liberation from the influence of conquering forces.

And so Bombay, Madras, Calcutta have become less used as names, just as Ceylon, Burma, Rhodesia.

The restoration of historical names suggests self-identification, as an exercise in self-determination.

Australia is not untouched by this trend either – with Melbourne increasingly known as Naarm and Brisbane as Meanjin (including, appreciatively, by members of our own Indian-Australian community, particularly those in the academic and artistic endeavours).

If “Bharat” is identity-stamping, then “Naarm” and “Meanjin” are the same.

After all, the quest for identity is not bound by borders, religion or nationalism: it’s an innately, almost pervasively human quest that draws us together, perhaps more than any other. When you call for Bharat, you tie yourself to that quest more generally; when you call for Bharat, you call also for Meanjin and Naarm.

These names are but part of the voices that Australia’s Indigenous people are asking us all to embrace in the upcoming referendum, in their own struggle for self-identification.

If you’re embracing “Bharat” as a name, then you’re a supporter of the Voice in the referendum.

Read More: G20 plus one minus two