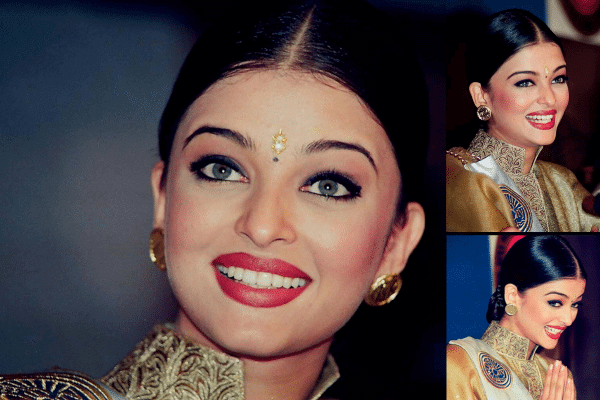

The year is 1994, and Aishwarya Rai has just won Miss World. Every press outlet in the country amasses at Delhi’s Taj Palace, eagerly waiting to clap eyes on the 21-year-old.

Amongst them is a prudent Guruswamy Perumal. He’s a long way away from his childhood in rural Tenkasi, rubbing shoulders now with politicians, film stars and even bandit leaders…

Most people would kill to be so close to such VIPs even once, but for Perumal, it’s just another day in his extraordinary photography career.

The woman of the hour enters – and despite being a seasoned photographer, Perumal can’t resist being bowled over!

“I saw her, this beautiful lady, and thought, my god, wherever she is looking is a beautiful angle [for her face]. I took her photo from 55 different angles,” Perumal remembers.

Perumal was so enamoured he went home and told his wife Kokila he’d ‘met the most beautiful woman in the world’. She curtly responded, ‘If I had that kind of money for makeup, I’d be the most beautiful woman in the world too’.

Regardless of Kokila’s assessment, it would seem everyone from Malayalam magazines to school children agreed on Aishwarya Rai’s radiance. Perumal sold them hundreds of copies of his photos.

In a career littered with memorable faces and places, this glimpse of a young Aishwarya Rai is Perumal’s most cherished moment, and to this day, those pictures retain pride of place on the coffee table in his East Melbourne flat.

***

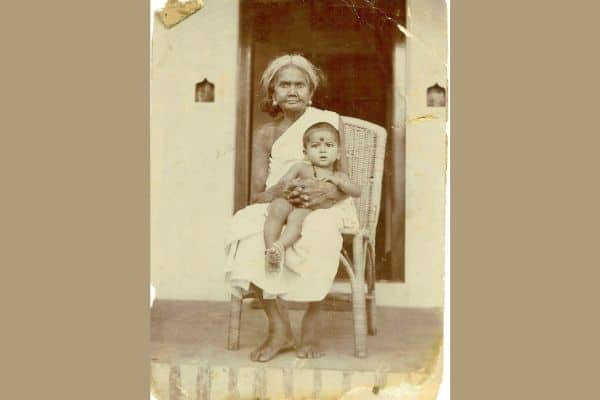

Photography has been a constant in Guruswamy Perumal’s life. The first of many photographs in his life was taken when he was just one year old, on his grandmother’s lap in Srivilliputhur, a grainy black and white picture fraying at the edges.

He remembers bringing it with him to Australia as a keepsake when his father passed. Taken in 1939, it reminds him of a simpler time.’

The eldest of five brothers, Perumal attended a Tamil medium school in Tenkasi, a quaint backwater in Kerala. Unlike his cricket obsessed peers, Perumal was a curious boy, preferring the company of pen pals and his stamp collection.

His father worked for the local postal department, so a camera was out of the question for their family. It was his wealthy friend Jawarali who introduced the young man to his first camera, an Airesflex.

Photography soon consumed Perumal’s day-to-day. By the time he’d finished school in 1957, he was waking up at 5am to capture fields and coconut trees.

“Nobody had this interest [in photography] – my whole family, friends, nobody. But I got it, I don’t know how. It was a natural, inborn habit,” Perumal says.

Of course, there wasn’t much scope for photography in Tenkasi, so Perumal followed his father into full-time work as a postal assistant. In his free time, he would pore over any photography books he could get his hands on and learn how to develop photos himself.

He recalls the anticipation of waiting for the tiny black and white photos to form.

“[You could take] only 12 very small snaps, and those days when you were taking photos, you could not see the result immediately. Only after seeing the negative and developing in studio could you see if it was correctly taken. It was very difficult, a risky job; nowadays photography is much easier, [the screen] gives everything,” he says.

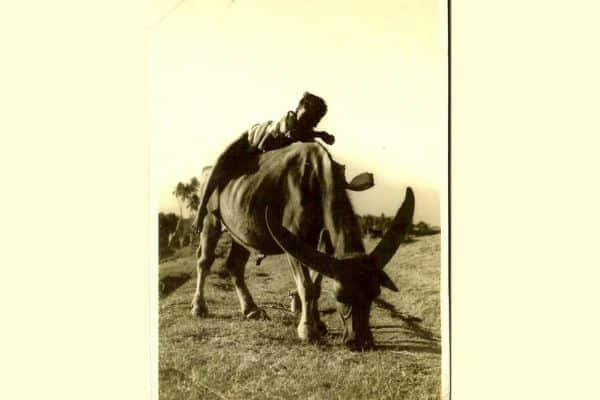

Eventually, he mustered up the courage to send one of his photographs to a competition – a boy lying on a buffalo, the evening sun setting behind them. Sadly, nothing came of it.

Disappointed, Perumal abandoned competitions, and did an about-face to portrait photography.

Life also changed course for Perumal, and in 1962, he wed Kokila. It was an arranged marriage, but luckily, she was someone who’d abide his true love, photography.

“I got lucky to get my wife. No complaints – she is happy. Before going to any function, I would take one or two photographs [of her] from different angles, and she liked looking at them. Even on my wedding day I was taking our photos.”

***

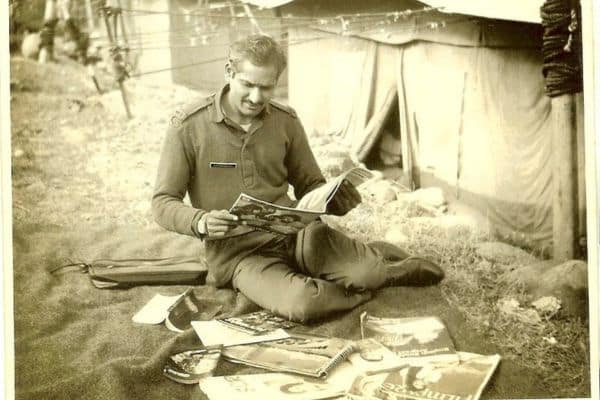

In 1971, Guruswamy Perumal joined the army’s postal service, and was posted to Akhnoor during the Indo-Pakistan war. He had always wanted to see north India, even if it meant sleeping in a tent in ‘horrible cold weather’.

Though Perumal never saw conflict like his brothers, he spent plenty of time around the border, frequently flying mail and other supplies to the jawans on the frontline.

Of course, imminent danger wasn’t enough to deter him from his favourite pastime. He recalls sneaking his camera onboard helicopter trips to Pallanwala.

“In the account bag, along with the letters, and without the pilot knowing, I just kept the camera, and when we started flying, I clicked from the backside of the helicopter which was open. You had to do it all very quietly,” he says cheekily.

Photography was still a hobby; he had enough to buy his own camera, a Nikon FM, but his various pen friends across the globe were the only ones who’d see the fruits of his labour.

But that changed during a posting to Delhi in 1974. Word spread about Perumal’s photography prowess amongst the higher-ranking officers, and he was given permission to document any visits to their unit. For the first time in his life, Perumal was paid to take photos.

He beams as he thinks back on the ‘privilege’ of accompanying Lieutenants and Generals.

“[Once], the Lieutenant General asked me what camera I had…I explained everything, and he was damn happy. He called me and said: ‘you please come visit our house, I also have this camera, we are in the same boat’!” he recounts.

Eventually Perumal found himself doing more photography than postal work. He became known to the higher-ups as the man who ‘paints with the camera’, invited to their homes to take their family portraits.

By the time he left the army in 1989, he’d developed a solid portfolio and confidence to boot. Perumal’s invitations to capture visiting Lieutenants turned into appointments with visiting Politicians, as he became the official photographer for the Tamil Nadu and Kerala Government in Delhi.

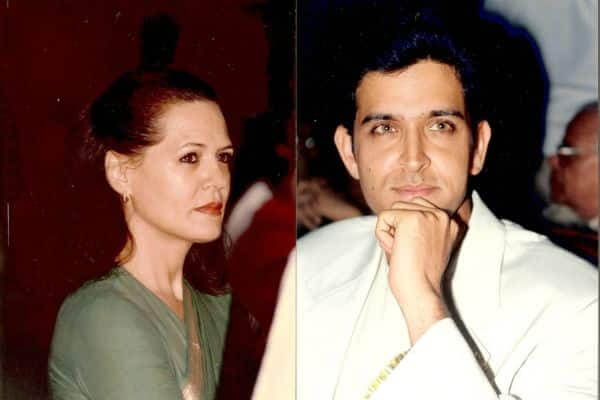

Over his 18-year stint, Perumal accumulated a long list of VIPs, from Tamil film superstar Kamal Haasan to literary super weight R.K Narayan, from Congress party matriarch Sonia Gandhi to bandit queen Phoolan Devi.

He rode the rush of the shutter, scrambling for angles and following his impulse to capture rare moments: “I met Mother Teresa at Lee Meridian Hotel in Janpath. She’s 5’3”, very small; she entered the hall with her face down – I was thinking, how can I take her photograph? So immediately I sat down in front of her and didn’t give her space to move, and she looked up – I caught her divine smile, click, click, click!”

Though constantly in spitting distance of prominent figures, Perumal never gave into starstruck reverence, always regarding them with the detached professionalism of a true pressman.

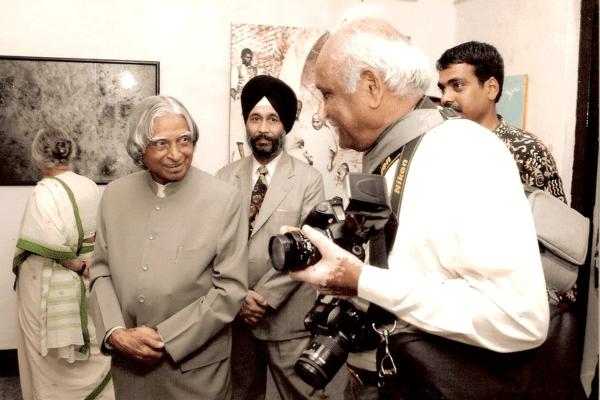

Of course, there were some exceptions, like the day he met fellow Tamilian former President of India Dr A.P.J Abdul Kalam: “He asked me how I was in Tamil, and I told him I had read his book [Wings of Fire] and I cried. He called me for a photograph!”

***

In 2008, Guruswamy Perumal and his wife Kokila left everything behind, migrating to Melbourne to support their daughter Meena with her brain cancer diagnosis.

Perumal went from being one of Delhi’s most popular shutterbugs to like a bug on the ground. Being ‘underqualified’ in the eyes of local employers and ineligible for pension meant they had no income besides the money they’d brought from India or borrowed from friends and family.

“We came with one suitcase only; here we were dependent on my son-in-law, that is not good. I tried to get a job as a photographer and in the post office, the only job I know, but nobody is going to give work to somebody 70 years old. They were not recognising me, so I worked without money. $700 per month – two, three years I suffered like that,” he says.

On weekends, Perumal photographed Indian community functions for various organisations and newspapers. Finally, through word-of-mouth he found a job at the Consulate General’s office, which saw him through the acclimation.

These days, Perumal is approaching ninety, his tired hands struggling to hold a camera steady for long periods of time like he once did. But old age hasn’t smothered his eye for a good shot.

‘The heart is in [it], I’m thinking I want to take [photos], but the body is not helping me,’ he says ruefully.

The slowing down of life has brought him back to nature photography, the walls of his East Melbourne flat adorned with sunrises and flowers he has snapped. For the first time in decades, he’s submitting his photos for competitions, sometimes even winning them.

And sometimes, when he peers through the lens of his camera, he thinks back on the extraordinary life he’s captured.

“So many interesting things happened in my life. This is a life. I’m lucky enough, [by] God’s grace I got this much.”

READ ALSO: The unbelievable story of Charan Dass