South Asia is crucial to the future of Australia. But Australia has just one (small) program focused on South Asian studies across its many universities.

This has not always been the case. In the mid-1970s, 13 of Australia’s universities offered undergraduate subjects on South Asia (India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives). Students could learn about South Asian coins at ANU and Sanskrit at the University of Wollongong.

Australia boasted some of the leading scholars on South Asia. ANU nurtured subaltern studies – the study of social groups excluded from dominant power structures – which became a global movement in the field of post-colonial analysis. Leading post-colonial scholar Dipesh Chakrabarty was based at the University of Melbourne. Other luminaries active in that period include A.L. Basham, Anthony Low and Robin Jeffrey.

But, even as the Australian university sector has expanded since the 1970s, it has withdrawn support for Asian studies, and South Asian studies in particular. There is currently only one South Asia or India program – at ANU.

Only five of the 40 Australian universities offer semester-length subjects on India or South Asia. Six universities offered an Indian language in 1996. Now only two do so.

Several universities, often supported by government grants, have launched country or regional research initiatives since 1990. The National Centre for South Asian Studies, based at Monash, is one of these. But Australian universities have not built any strong or sustainable South Asia programs for students.

A trend at odds with national priorities

This point sits oddly alongside a high-level commitment to South Asia in Australia. The Australian government is exploring new forms of engagement with India, including the Quad security dialogue involving India, Australia, Japan and the US.

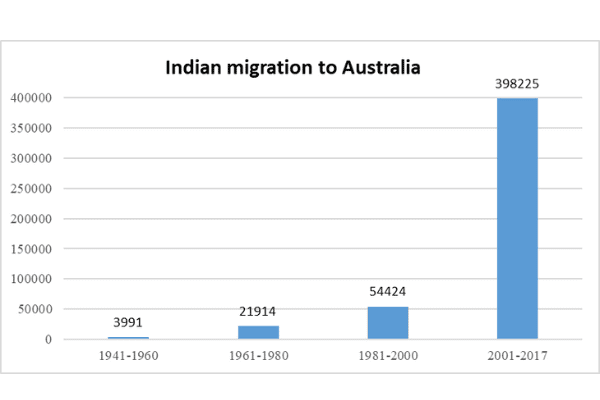

At a social level, Australia is increasingly Indian. In 2019 more than 700,000 people in Australia claimed Indian descent. Hindi is among the fastest-growing languages in Australia, and India is the country’s leading source of skilled migrants.

Historically, there are fascinating connections between Australia and South Asia. The lives and work of Australia’s “Ghans” (cameleers) is one famous example.

Moving forward, Australia needs a knowledge base to match this longstanding and increasingly important commitment to India and South Asia more generally.

Out of step with global academic practice

Australian universities could learn from their counterparts in other parts of the world how to integrate area studies into their teaching. Outside of Australia, most of the top universities in the world make great play of their area studies expertise. Area studies enables people to apprehend their own distinctive humanity, anchors innovative cross-disciplinary teaching across the university, and provides a basis for re-evaluating assumptions about a person’s disciplinary field.

Students arriving at Oxford, Yale or Columbia know that if they are studying law, business, art, politics, education, design, technology, anthropology, economics, agriculture, military affairs or modern media, they will need to think about how to apply their disciplinary knowledge to specific places. A “whole of university” commitment to area studies teaching, including South Asian studies, has long been a key mechanism for drawing on multiple disciplines.

Even with small numbers of area studies majors, the world’s best universities do not see area studies as a niche endeavour. On the contrary, they see it as a central feature of their global mission. Strong universities without robust, independent, and widely accessible area studies programs open themselves up to accusations of antiquated parochialism and a poor understanding of the interdisciplinary trends that powerfully shape our world.

What should South Asian studies offer?

Today, South Asian studies programs in Australia should include internships, opportunities to study abroad and virtual classrooms connecting Australian students to their counterparts elsewhere.

Asian studies programs should also include language options, because effective communication with rising regions like South Asia is essential. Keep in mind that only 10% of India’s population speak English.

At its most fundamental, good area studies and good South Asian studies allow people to understand that they are, as French philosopher Michel de Montaigne put it in an essay on global education written 450 years ago “like a dot made by a very fine pencil” on the world map. It teaches them how they fit within a global whole.

Beyond this, area studies helps people understand and confidently engage with forms of difference and diversity. It fosters key skills for interacting with peers overseas as well as global diasporas. This includes connecting with foreign organisations, managing communications and cultivating an active sense of global citizenship.

Area studies allows us to develop an understanding of our common humanity across national boundaries – something Indian scholar Veena Das has written about in her book Critical Events.

Now is the time for Australian universities to place area studies teaching at the core of an internationally engaged education. We must provide a much larger number of Australians with a deeper understanding of South Asia.

First appeared on The Conversation, written by Craig Jeffrey, Professor of Geography, The University of Melbourne, and Matthew Nelson, Associate Professor, Asia Institute, The University of Melbourne.