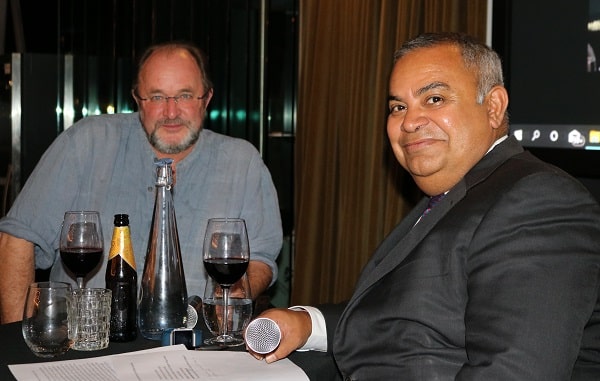

Pawan Luthra: William, your latest book, The Anarchy has just hit the stores and is on the best sellers list everywhere. It sits at the middle of the end of the great period of the Mughal Empire and the start of the Raj. What compelled you to write about this period?

William Dalrymple: Everyone in India knows about the great Mughals, about Shah Jahan and the Taj Mahal. Everyone knows about Lord Curzon and the Raj and Queen Victoria and all that stuff. But in between those periods, you have this extraordinary world which breaks all our expectations. It’s a world where it isn’t the British Empire which is running India, but one multinational corporation, the first multinational corporation, the East India Company. It was not initially in any way involved with the government for the first 170 years, from about sixteen hundred through to 1770.

It was, you know, a completely libertarian, ruthless capitalist organisation which performed the hugely improbable feat of taking over the richest empire in the world. And when it started, in the year 1599, just to give you the context of this, Britain was producing about 3 per cent of world GDP. And at that period, the Mughal Empire was producing about 37.6% of world GDP. In other words, well over a third of world GDP. And for the first time in history, India, by which I mean most of modern India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and most of Afghanistan, which was what made up the Mughal Empire, had overtaken China as the world’s leading industrial producer.

I think today in India, there’s a tendency to see the Mughals as these effete kings building ridiculously expensive tombs and prancing around in Bollywood outfits. In actual fact, from the point of view of economic history, they were the most successful Indian dynasty of all. And in the early 18th century, just when politically the Mughal Empire was in a sense beginning to fracture, their economic power was at its peak, largely due to the textile industry in Bengal. By Bengal, I mean Greater Bengal, which embraces modern Bangladesh, Orissa and Bihar. That area was the world’s manufacturing hub of textiles in the 18th century, the same way that Manchester became a century later.

A million weavers at work, producing not just incredibly high quality and cheap and competitive cotton, but chintzes, kalamkaris, fine silks with weave so fine they were called baft Hawa- woven air. This incredibly competitive and remarkable industrial produce conquered not just Europe – every Frenchman, every Dutchman wanted a kalamkari hanging around his bed – but also as further afield as Mexico. The East India Company initially rises up as basically the shippers of this material around the world. And they are parasitic or symbiotic with the rise of Mughal industrial power. So this was a period when India was unbelievably wealthy. Millions of pounds in weight of British and European gold and silver are pouring in not just from Britain, but from Portugal, Holland and Denmark. It seems right up until the middle 18th century that this is a loss of gold bullion to Europe and again to India that is irreversible.

This has been something which has been the case in Indian history since the time of Pliny in the first century, very austere Roman writer, contemporary with Jesus and Augustus, who complains that such is the decadence of Roman womanhood, that all they want to do is wrap themselves in gorgeous silks, rub their bodies with sandalwood paste from India and to hang from their ears Indian diamonds.

The idea that we are now seeing ahead of us of India as this big industrial growing power with an incredible future, is not something new and odd and surprising; it’s just a reversal to what has always been the case and only stopped being the case due to European firepower. And this very brief period between Vasco de Gama in the 1490s and 1947 – 500 years – is breaking what has otherwise been 3,000 years of economic dominance by China and India.

Photo Credit: Rinto Antony

Continue reading: William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy: A story of how far corporations can change the world