William Dalrymple: The ‘ravaging territorial appetites’ that finally saw the East India Company cut to size

Pawan Luthra: The famine in Bengal in 1770 began the downturn of the Company. How did it exploit this major calamity?

William Dalrymple: So the East India Company screws up, as corporations often do, through greed. We’ve seen in our old day’s many examples of corporations which seem impregnably strong, impregnably dominant economically and whose share price seems immovable, suddenly collapse when circumstances change. And this happens to the company in 1770. 1764, it’s finally conquered all of North India with the Battle of Buxar: it takes them only six years to asset strip, loot and plunder Bengal so thoroughly that when the famine of 1770 comes, there are no surpluses.

There are no granaries stocked with grain. The Company is not in the business of setting up soup kitchens; as a company, it’s there unequivocally to make a profit in the same way that Goldman Sachs is there to make a profit today.

So when the famine comes, the Nawab of Awadh at the same time builds imambaras and employs 100,000 people. And they live. In Bengal instead, one million Bengalis die, a fifth of the population of Bengal.

The East India Company – by sending sepoys out into the villages and gathering tax revenue by force, and hanging anybody who doesn’t pay – manages to maintain revenues at pre-famine levels. The shareholders in London vote themselves an increased dividend from 10 per cent to 12.5 per cent. This happens for two years. Then finally, in the third year, there’s nothing left. As one Scots writer and whistleblower writes, ‘They have picked the Bengal bones to the marrow and it lies bleaching in the wind.’ The share price sinks, 30 banks collapse across Europe. It’s like the subprime, but only worse.

And this is the moment that for the first time in its history, the government begins to take an interest in the East India Company. Up to now, they’ve been a valuable source of customs revenue, and no one has asked too many questions about where this money is coming from. It provides a third of British customs and it pays its taxes and the government’s fine with it. Suddenly, whistleblowers are writing reports of a million bodies in the streets of Calcutta, the Ganges clogged with corpses, vultures and dogs barking at human remains, clouds of flies and vultures like some biblical plague.

And suddenly everyone in Britain wakes up to the fact that all this stuff is going on and there is outrage. There are angry editorials in the newspapers. Parliament has to bail out the Company because it is literally too big to fail.

So the East India Company in 1774, through its own greed, puts itself in a position where it is bailed out by the government. So the government now has a regulating role over it. And from that point onwards, it changes from this buccaneer libertarian organisation, unregulated, unwatched over, just a source of money, to what would today be called a public-private partnership.

Eventually, in 1857, it screws up a second time during the Great Indian Uprising, and three hundred thousand are killed in the reprisals. And as India is nearly lost to Great Britain, the government rolls up the Company completely and in our terms, is nationalised.

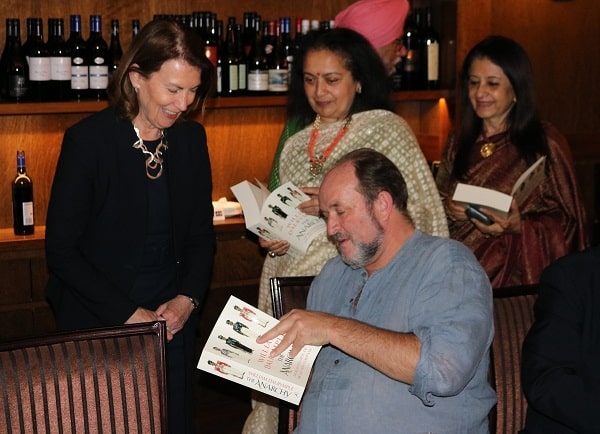

Photo Credit: Rinto Antony

Continue reading: William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy: A story of how far corporations can change the world