As a seven-year-old child growing up in Kasargod in Kerala, Dr Ramananda Kamath watched as his family’s buffalo delivered a calf. Three days later, he would watch the young calf froth at the mouth consistently, convulse and die.

It was a memory that stuck on, and one that pushed him towards medical science.

“It took me more than thirty years to realise what the poor animal was going through,” Dr Kamath told Indian Link. “It’s what we do a liver transplant for in young children.”

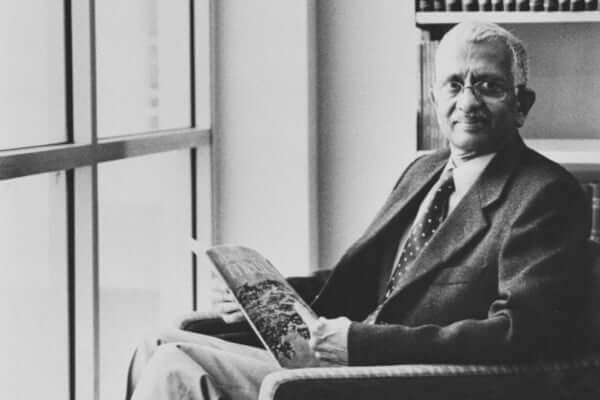

Today, Dr Kamath has received an OAM honour from the Australian government for his extensive work in paediatric gastroenterology, including pioneering work in liver transplants in children.

It was in the 1970s that Dr Ramananda Kamath established the new department of paediatric gastroenterology at Children’s Hospital Camperdown Sydney, which later became Westmead Children’s Hospital.

“It was one of the first in the world, alongside select hospitals in the US and Europe,” Dr Kamath said. “My brief was to comprehensively cover the entire digestive system, covering every organ involved from the mouth downwards, and the liver.”

As Head of the Department, Dr Ramananda Kamath and his colleagues performed Australia’s earliest liver transplants on children.

“The instruments were only just being developed,” Dr Kamath recounted. “We didn’t have little scopes to use with children. I travelled to Saint-Pierre University Hospital in Brussels, where someone had devised a scope from a new Rolls Royce invention – tiny scopes to look inside airplane engines. It worked wonderfully for us.”

Having learned how to use this and other pieces of equipment, Dr Kamath taught others in his department at Sydney.

“The processes of learning and teaching went on concurrently,” he laughed.

And yet, he has seen his wards who learned from him, go on to practice across the globe – in Perth, Brisbane, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Surabaya, Coimbatore in India, and Liverpool in the UK.

“I feel great at the OAM honour,” Dr Kamath remarked. “And obligated to this country which gave me a chance to flourish when my own country did not.”

A linguistic minority in India as a Konkani speaker, he detailed how he was discriminated against as a student and as a young doctor starting off. “I struggled to gain entry into medical college in a state outside my own, even though I was a high-achieving all-round student. I struggled to find a job even after finishing medical college with remarkable success.”

Ultimately, he managed to finish his MBBS at Madras University, and did an MD and DCH (Diploma in Child Health) at the prestigious CMC Vellore.

It was at Vellore that he finally got his first job, conducting epidemiological research for the US Public Health Service, now called the Communicable Disease Centre (CDC).

After brief stints in St. Bartholomew’s Hospital London, and in Malaysia with his Malaysian-born Indian-origin wife, he moved to Australia.

“Even though I had a job waiting for me here, I had to wait a full year to get a visa,” he recalled, laughing.

Besides his work at the hospital, Dr Kamath undertook private practice – he never charged the young families that came to see him.

View this post on Instagram

Meanwhile, the hospital department he established continues to flourish, now subdivided into five specialty branches. “A portrait of me hangs in the library, I’m told – it’s where I spent a lot of time.”

As an 87-year-old now, Dr Ramananda Kamath has spent the last twenty years in retirement, exercising, singing, reading, and keeping up to date on technical advancements in his field.

How would he advise young doctors considering a career in paediatric gastroenterology?

“It’s an expanding field. Get used to the term ‘non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)’, or ‘metabolic (dysfunction) associated fatty liver disease MAFLD’, as it is now being called. I never saw a single case during my working years, but it now affects one in four Australian adults and many children. Seen in people who are overweight or obese, it is caused by wrong diet habits and poor lifestyle choices. It can be prevented completely if caught early. Similarly, be prepared for inflammatory bowel disease, of which Australia has one of the highest rates in the world.”

He added as an afterthought, “Don’t go by hip pocket alone. Part of the problem with young doctors today is they are motivated by lifestyle. So they won’t go to country areas, for example. You must have not only desire, but also passion. I myself had tremendous interest to become a doctor, even though I came from a family of lawyers.”

How does Dr Kamath reflect on his own career today?

“It’s been a journey of seeking knowledge; putting it to practice; ensuring my patients were prevented from disease and death at low cost, time and money, and influencing a new generation of doctors.”

READ ALSO: Dr Sachint Lal, OAM: Australia Day Honours 2024