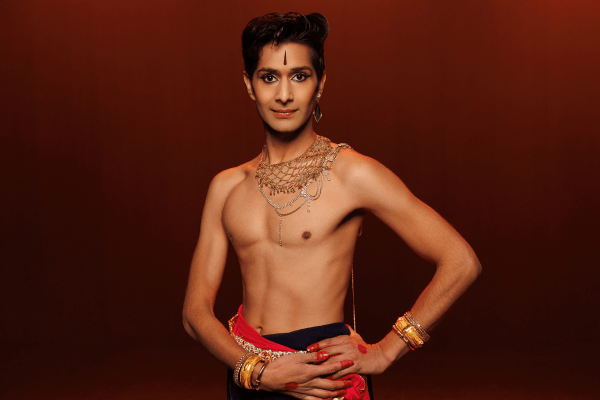

Well-known Melbourne dancer Govind Pillai gives a sneak peak of what to expect in his upcoming and much awaited production ‘Temple of Desire’.

The Melbourne Fringe staging will open with a sequence which is performed entirely with the dancers’ backs to the audience.

“It is an homage to the devadasis, and their performance being solely for the benefit of God,” Govind explains. “The dancers invite the audience to consider what the spiritual beings are seeing from the front’

The show is about looking back several thousand years to a precolonial world, trying to reimagine an art form that was fully liberated.

“We are keen to try and rediscover that place – the place where a lot of the misogyny, casteism, and patriarchy that is in the art form doesn’t exist, and the current sanitisation of sensuality is rediscovered,” Govind says, describing the intent behind the work and its aesthetics. “We are trying to go to a place that is pre Sanatana Dharma (pre Hinduism), so the costumes are inspired by tribal aesthetics. The jewellery will be thick chokers in metal (gold), and the costume colouring is more austere – ash and grey – as we are trying to bring most of the ‘colour’ to the show from the human form itself.”

The ensemble piece ‘Temple of Desire’ is a culmination of a decade of award-winning solo performances by Govind, and duets with his dance collaborator Raina Peterson (a Mohiniattam dancer by training).

At the very core of the show is Bharatanatyam, inspired by companies like Sridevi Nrithyalaya and Aayana Dance Company. Govind cites the challenges of elevating the traditional dancer body (as described in the Natya Shastra) whilst also breaking form. “If we were not bound by the tradition of what we have been taught, how would we move as people and not as classical dancers?”

The ensemble has been chosen for their ability to portray the breaking of form as a provocation, giving the audience a vague sense of familiarity amongst the entirely unknown – a show where male-seeming characters depict emotions outside of what is expected within gender constructs.

Govind himself says that finding identity is an ongoing challenge. “There are moments where I break into full-on classical (dance), and other moments I feel constricted by the form.”

Most important for Govind is the risk of staging ‘Temple of Desire’ in a community where traditional values still adorn the stage and mindset of many dancers.

“It deals with a heavy amount of intersectionality that we really need to face today. We are looking at feminist, queer, trans progressive, gender diverse work being told through classical Indian dance, and that’s really bold and difficult for us… these kinds of events succeed by word of mouth and there’s a lot of hesitance to embrace stories like this told through a classical dance form.”

One of the key heroes boldly displays their gender reassignment surgery scars, and the production prominently celebrates brown bodies. Govind asks “What would the image of a goddess look like if we were to disrobe rather than neatly adorn?”

Govind is the co-founder and co-director of Melbourne based ‘Karma Dance’ (@karmadanceinc).

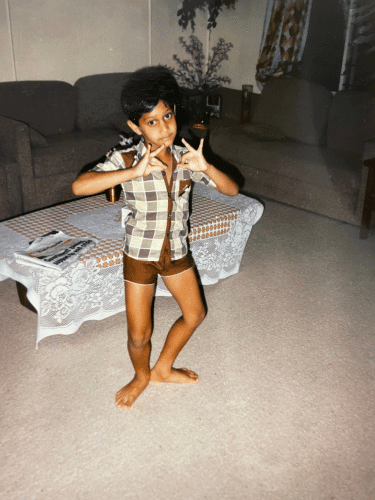

He started dancing at a very young age, at a time when male dancers were not prominent, “I learnt adavus (the basic steps) in my bedroom, as a game where my sister was the dance teacher, and I was the student” His passion was subsequently discovered by his mother, and he was enrolled into formal classes.

Since then, Govind has also developed strong contemporary dance skills and has briefly forayed into ballet.

Karma Dance was originally formed to raise funds for South Asian domestic violence support services – a cause very close to Govind’s family. Karma Dance’s body of work share a common theme of showing the suffering of marginalised groups with feminist overtones. Govind skilfully balances his own learning and dancing with a strong teaching presence, having presented student arangetrams which also embody these progressive themes.

Govind recalls his most memorable body of work as being ‘In Plain Sanskrit’ (2015) with Raina Peterson, as it was the first time he stepped away from the traditional Bharatanatyam format in a stark way – no jewellery, austere costuming and music sung by the dancers on the stage.

“This was a formative part of my dancing – I recall how very much out of my depth I felt in reimagining the artform.”

Govind is appreciative of two strong influences in shaping the dancer he is today. The first is Bharatanatyam dancer and choreographer Hamsa Venkat (Samskriti School of Dance) in fostering Govind’s self-awareness. “She said to me, ‘it’s time to leave absolutely everything on your birth certificate at the door’”. He continues to try and give justice to this sentiment in his creative concepts.

Anna Louise Paul, a Sydney-based flamenco and contemporary dancer, is his second inspiration. “Anna helped me understand ‘breaking form’, and finding the contemporary within a cultural practice.”

After Melbourne Fringe, an excerpt of ‘Temple of Desire’ will be performed at Woodford Folk Festival in December and the team hope the production can be shared at Queer festivals and other arts spaces across Australia.

We hope Govind Pillai and the Karma Dance team will continue to be able to create and perform this revolutionary body of work across the country and internationally.

For details about ‘Temple of Desire’ at the 2024 Melbourne Fringe Festival, head here.

Read more: Melbourne Fringe 2024: South Asian links