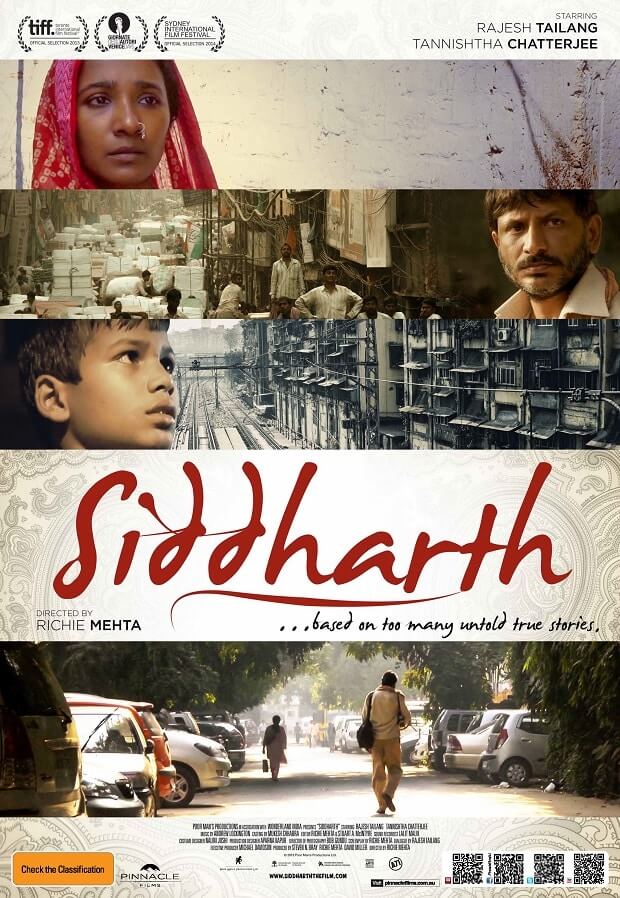

Canadian director Richie Mehta explores the world of child exploitation in India, writes KIRA SPUCYS-TAHAR

Growing up in Canada, Ontario-born film director Richie Mehta had a romantic ideal of the India his parents had left behind. But after travelling there on a family holiday, he was faced with a disturbing economic reality and found it difficult to reconcile these two opposing visions of the country of his heritage.

In 2010, on a trip to Delhi, Mehta was speaking with a rickshaw driver. “He told me he thought his 12-year-old son had been kidnapped,” Mehta recalls. “He had no picture, and couldn’t spell his son’s name. He had been searching for him for more than a year.”

The man was trying to find a place called ‘Dongri’ where he suspected his son had been trafficked. Due to the man’s circumstances, being illiterate and too poor to own a camera, forced to work every day to support his family, he could only ask others for help. Mehta was able to use the internet on his phone, search and locate ‘Dongri’ in seconds.

The desperate tragedy left a great impact on Mehta and nine months later, while working on another project, the story was still haunting him.

Mehta’s new film, Siddharth, resonates beyond the cultural nuances of India. It is a global film that engages with the evolving international environment where, though conventional geographic barriers are negotiated with the help of technology, at a basic level, thousands of people are faced with a world they cannot control or understand. “The story of Siddharth is in line with how I want to discuss the compassion and integrity in Indian people, despite their economic situations,” Mehta says.

Working on his debut film, Amal, in Delhi in 2008, Mehta wanted to do everything by the book. He tried to arrange permits and work within the bureaucracy, but found himself mired in red tape. This time around, he worked with a small crew, pre-planning scenes before jumping in to film and quickly disappearing.

“You have to work around and through the chaos,” Mehta says. “We worked to capture the traffic, the people, the train stations, the market places. We wanted to integrate that environment.”

Siddharth mirrors elements of the tale Mehta was told by the Delhi rickshaw driver. The film is a quietly moving exploration of daily struggle in 21st century India, where poverty forces thousands of Indian families to send their children out to work. It is also layered with a passionate indictment against child labour and child trafficking.

Mahendra, a Delhi chainwallah who fixes zippers, sends his son, Siddharth, to work in another city and earn money for the family. When Siddharth fails to return home for Diwali, Mahendra begins a difficult journey to search for his lost son. The film goes beyond the typical Hollywood conventions to bring a brave sense of realism to the final act while still giving the audience a sense of hopefulness for the future.

Though Mehta grew up speaking Hindi, he wrote the entire script for the film in English. The film’s lead, Rajesh Tailang, a professor at National School of Drama in Delhi, did the translation of the script into Hindi. Tailang gives a quiet but powerful determination to the character of Mahendra. “The film was very much a collaborative process,” Mehta says. “So much of this also rests on his shoulders.”

Tannishtha Chatterjee, as Mahendra’s wife, Suman, brings poise and dignity to the role of a mother faced with the loss of her son, forced to learn her husband’s trade in order for the family to survive. “They are both very good friends of mine,” Mehta says. “I knew I wanted her to be involved from the beginning.”

As part of his research for the film, Mehta spoke with a man working in India as a child trafficker. “He told me he wouldn’t be doing it unless there was demand for it,” Mehta says. “It’s the cycle of the industry. There are some serious socio- and psychopaths out there and it’s a supply and demand market.”

In his journey to find Siddharth, Mahendra encounters a series of characters who, in spite of first appearances, want to help him. The fear and dread permeating the film sits as an undercurrent beneath Mahendra’s optimism and hope.

Mehta’s film simultaneously challenges and conforms to Indian tropes. “People who’ve not been to India see it as a different planet,” Mehta says. “I use markers in the film to bring the audience in, like the characters’ use of mobiles phones, to make them see how they can fit into this universe, the similarities between countries and cultures.”

“I’ve been making films for 10 years now,” Mehta tells Indian Link. “I’m still young, but I hope people connect with my work. The reason I’m doing this is not about fame or success, it’s about telling stories.”

Mehta’s favourite film director of all time is Australia’s Peter Weir. “In his work, the content defines the execution,” Mehta says. “You learn and feel something is added to the experience every time you watch his films.” Mehta refers to Weir as ‘the Guru’ and says he aims to emulate elements of his directorial style: “He makes these grand scale films, but they’re still very intimate for the audience.”

Mehta says he is “entrenched” in the world of Delhi now. “I am attracted to the darkness associated with Delhi. Indians say it is the ‘coldest’ city, in terms of interactions with people, but to me it is aesthetically the most beautiful,” Mehta says. “There is a real attitude, a real dark sense to the city. If you find compassion there, the people really mean it.”

The major difference between this film and his last major Indian project, Amal, is that Siddharth is being released all over the world. “This time I knew what to expect,” Mehta says. “I’ll do anything for a film. The writing and directing came from a very personal space. It all started as an experiment, I just want people to see the film.”

“Whether the film succeeds or not, someone very close to me, whom I respect, gave me some great advice: ‘If you write your own material you’ll never regret it’. Even in hindsight, I’m happy. I did that best that I could have done at the time. Other directors can go from one incoherent project to masterpieces, but I want to be satisfied with every one of my works.”

In fact, Mehta’s first love is science fiction and fantasy. His first English feature film, I’ll Follow You Down, about the disappearance of a young scientist on a business trip, was filmed in Toronto just before Siddharth. “Everything was designed, as opposed to being planned to capture the chaos. The film is orchestrated more in the edit, whereas Siddharth is about what you can get on film,” Mehta says.

Other projects on the horizon include another Indian social film, a true story about a female police officer involved in a major manhunt. “It’s based on another true story,” Mehta says, “Another one that hit me in a personal way.” Another upcoming project will take him to his family roots in south India, filming a movie about a family, a young girl and a runaway elephant.

“I’m spending so little time in Canada now,” Mehta reveals. “It’s more difficult for me to integrate every time.” He intends to keep “fighting the battle on the social front” in India.

“It’s important to be and learn and to be open to what that means,” Mehta continues. “I’m not one of those yoga pants people, those people in the ivory tower. In India, it’s not about what you expect, it’s about being prepared for the possibilities.”