You may think nothing about dropping $5.50 for a pot of masala chai at your local café, but this fact might make you set your cup down: the price of that chai is almost twice what a tea leaf picker in Assam might earn for an entire day’s worth of back-breaking work. These low wages perpetuate a cycle of poverty, malnutrition, low levels of literacy and health, and, even more worryingly, human trafficking and modern slavery.

Now, an Australian non-profit organisation wants to change that.

Project Didi Australia, which is dedicated to transforming the lives of women and girls in Nepal at risk or affected by sex trafficking and abuse, launched an initiative called #somethingforslavery on 21 May this year, calling on Australian tea brand T2 to commit to a living wage for tea workers. The date was chosen as it was the first International Tea Day celebrated by the United Nations. The purpose of the day is to “foster collective actions to implement activities in favour of the sustainable production and consumption of tea and raise awareness of its importance in fighting hunger and poverty.”

“We wanted to communicate to the community in Australia that there is a direct link between trafficking, slavery and the products we buy here through global supply chains,” explained Project Didi board member Clare Bartram.

For the project, Project Didi has teamed up with Be Slavery Free, which works to prevent, abolish and disrupt modern slavery in Australia and around the world.

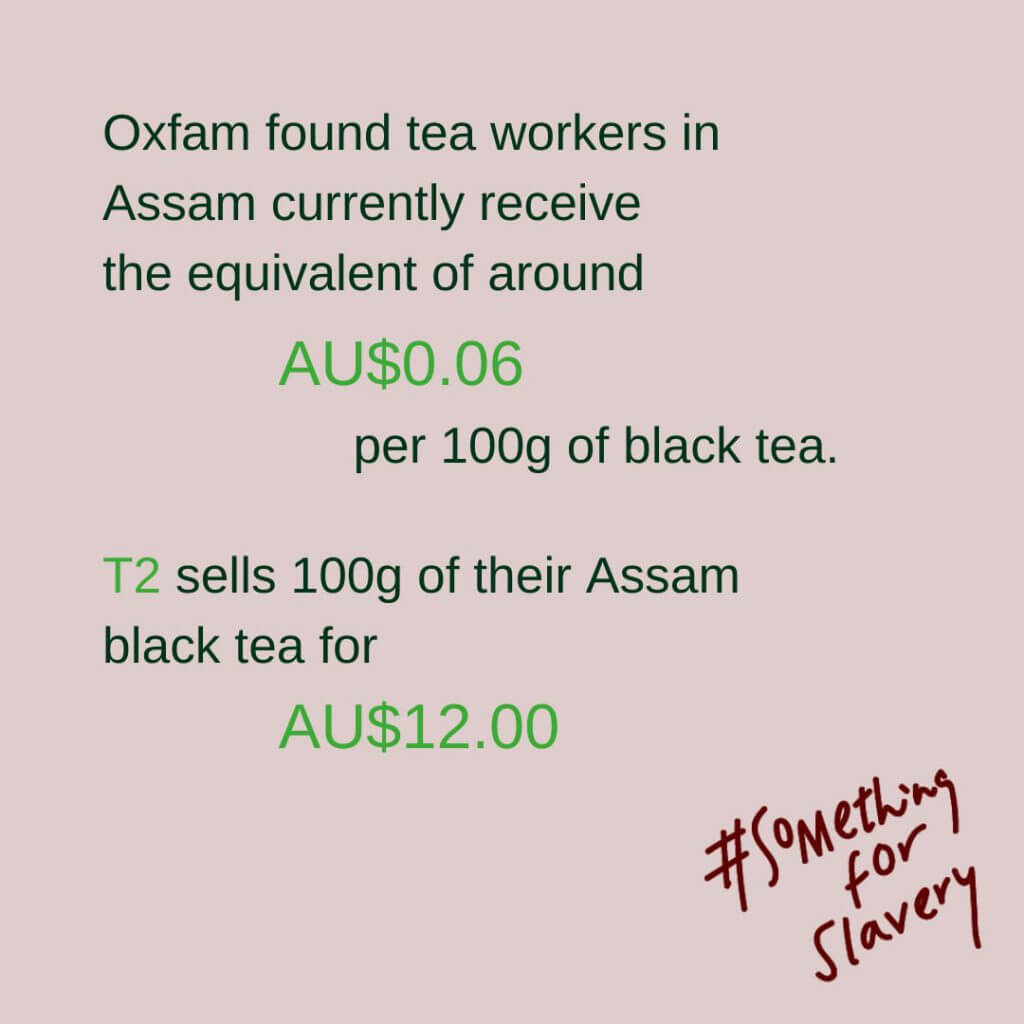

Slavery has a clear link to poverty, and tea leaf pickers in Assam are some of the poorest people in India, earning as little as $2.80 a day. A 2019 study by Oxfam found that the workers receive around $0.06 per 100 grams of bagged black tea while T2 sells 100 grams of its Assam black tea for $12. Oxfam also estimates that the workers will need to be paid only $0.15 more to earn living wages.

Bartram explains that the reason for such low wages is that, in India, plantation owners are required under law to also provide them housing, food, health care and childcare.

“The problem is that plantations often inflate the value of these services to justify paying the low wage,” she said.

This means the workers face a double whammy. They get paid a poor wage – just over half the legal minimum wage – and they live in abysmal conditions, which include leaking houses, poor sanitation facilities or no toilets, and substandard or very little food. The plantations have limited resources too – barely 5 per cent of the profit trickles down to them to pay the workers.

“There is a lot of evidence that when workers do not have enough to survive, they are much more susceptible to sending their children away,” Bartram said. This makes the children, especially girls, easy pickings for so-called ‘agents’ who lure them with promises of a better life in the cities, only to sell them to other agents or employers. This is generally sex trafficking or domestic servitude.

However, a good wage can change that. According to Bartram, a living income helps workers send their children to school, avoid debt and protect themselves against traffickers.

As to singling out T2, it is because the company represents a boutique segment of the market.

“T2 consumers are more thoughtful about where their tea has come from and would be more engaged in the campaign,” she elaborated.

The other reason is that T2 is owned by Unilever which, along with two other companies, owns 80 per cent of the global tea market. Unilever sources its tea from company-owned tea plantations and a network of suppliers, which includes over 300 suppliers in Assam alone.

Those who sign up for the campaign through the website or Instagram can directly email T2, host a (virtual) tea party with their family or friends to spread the word about the initiative, or post tea party pictures on social media and tag T2 in it.

According to the campaign page, they are “asking T2 to commission an independent study of what a living wage would be for tea workers in Assam and develop a plan to raise their wages and living conditions to achieve this within three years.”

Such campaigns have worked in the past. Tea drinkers, by virtue of their numbers, have used their purchasing power to influence tea companies. Bartram cites the example of a customer-driven campaign in the UK due to which six major tea companies, including Unilever, made public a list of their suppliers.

Bartram stressed that this is not a name-and-shame campaign.

“We are asking people to keep buying T2 but also contact them and say ‘As a consumer, this issue is really important to me. I love your tea from Assam and I want to make sure that when I buy it, I know the workers are treated fairly,” she said.