People hold their truth in their stories. Their joy and their pain. Some of it, and all of it. Storytelling is and always has been part of the nucleus of connection and community.

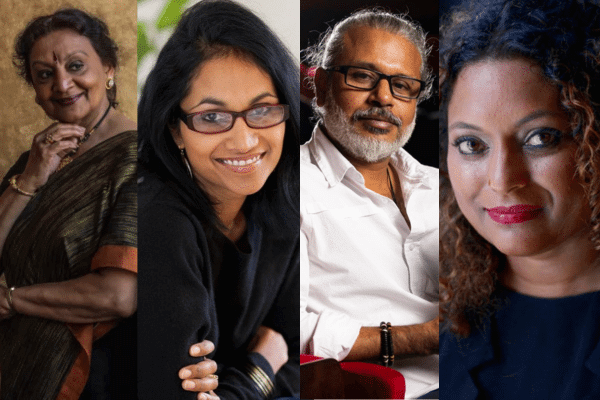

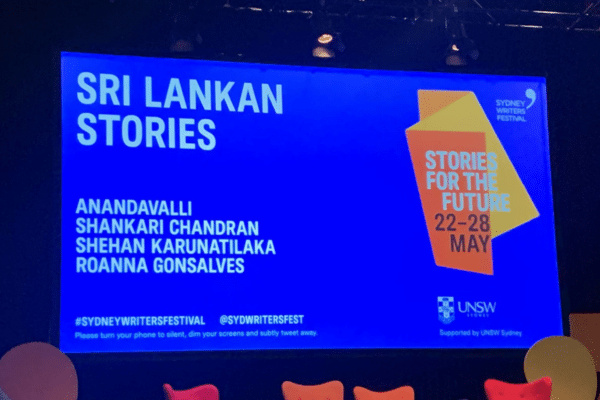

Hearing the stories of three impactful writers and artists at the Sri Lankan Stories segment of the Sydney Writers’ Festival 2023 was a nourishing eye opener. The 26 year long civil war was a focal point – to speak and write about Sri Lanka without reference to it almost always feels incomplete. But what struck me the most at Sri Lankan Stories that despite how different each writer’s perspective of the country was, there was a deeply shared sentiment of sorrow and guilt.

I grew up in awe of Anandavalli – she was instrumental in advancing classical Bharatanatyam dance in Australia. For her, Sri Lanka does not just represent a hometown that she looks back on with fond nostalgia. It was, and is, in a way, her soulmate. A love that was so great, that the loss of it was nothing short of unbearable. Her son, playwright Shakthidharan, captured this beautifully through Radha, the main character in his award-winning play Counting and Cracking. Although I’ve seen the play twice, I felt the dichotomy of Anandavalli’s experience to a much deeper level hearing her describe, through Radha’s character, her decision to leave Sri Lanka after the bloody riots of 1983.

“How could Sri Lanka do this to me? The country had broken my heart. Growing up I thought we were, and that it was, indestructible. But it wasn’t. What we had built was fragile. So fragile it was being worn down. Brick by brick. Until one day, people were turning around and killing the person on their left. On their right. The person in front. Or the person behind you.”

Contrastingly, Shehan Karunatilaka, winner of the 2022 Booker Prize and very modest about his exceptional writing talent, powerfully encapsulates in his novels Chinaman and The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, the version of Sri Lanka that tourists know and love. The warm Colombo hospitality, the comforting any-hour arracks and a unifying passion for cricket. Refreshingly with Chinaman, Shehan challenged himself to write a novel about the country that did not mention the war or the underlying ethnic conflict.

Arguably, this is a privileged position to be able to take, which Shehan rightly acknowledges, well aware that experiencing life as a Sinhala Buddhist in the insulated cocoon of Colombo, relegated the war to a mosquito buzzing in the background. It could be heard, loudly at times, but was not often directly seen. Yet as Roanna Gonsalves, the evening’s host highlighted, the levity with which he writes is magical, somehow making the tragedy more tragic in a very compelling way.

It was probably the perspective of Shankari Chandran that resonated with me the most. In her first novel Song of the Sun God, she poetically articulated the grief, rage and guilt that so many of us Tamil diaspora were flooded with in May 2009 as we helplessly witnessed the brutal end of the civil war from thousands of kilometres away. In a world where reality is determined by the loudest voices of those most powerful, fiction is how she was able to hold the truth of what happened.

Unlike Anandavalli and Shehan, there is greater distance between her and the country in her version of Sri Lanka, much like mine. For many, and dare I say most, second-generation Tamil diaspora, Sri Lanka isn’t really a home of any kind. It tends to hold tightly to the label of the island that once nurtured our parents but subsequently tortured our people, and for some, it holds no label at all. For me, home is mostly Australia. But the ‘where are you froms’ sting a bit more and a bit differently because in my story, I’m from somewhere that didn’t want people like me, and I never quite understood why.

The easy and mostly accurate answer is to blame the colonisers. Because let’s face it, they have been the instigators of so much conflict and chaos around the world. But Shehan’s words from Chinaman are worth deep contemplation.

“By the 1950s we started to develop our own dangerous ideas without any foreign assistance […] Ideas that have clashed and exploded for the last 30 years […] Whatever differences there may be [between Sinhalese and Tamils], they are not large enough to burn down libraries, blow up banks and send children onto minefields. They are not significant enough, to waste hundreds of months firing millions of bullets into thousands of bodies.”

Perhaps there is a need for us to reflect more deeply and look inward. Perhaps we need to examine the degree to which our finger pointing and blame has unhelpfully disguised our own shame. Sri Lankan stories, our stories, are a necessary way for us to express our truths and heal our trauma. But they are also an opportunity for us to re-write and re-shape our futures.

“Our stories serve as a mirror in which the public can see itself without mascara or styling gel. From us you learn the state of your nation. Sometimes the image you see in that mirror is not a pleasant one.” – Counting and Cracking, 2019.

READ ALSO: Desi reads at this year’s Melbourne and Sydney Writers’ Festivals