Historian, writer, art curator, also an award-winning broadcaster and critic, William Dalrymple has quite exceeded himself with his latest book.

The towering 522-page tome, which was in the making for six painstaking years, thoroughly dissects the machinations of the East India Company (EIC) that began as a trader but gradually became an occupying power before it was cut to size — but exists even today, owned by two brothers from Kerala “who use it to sell ‘condiments and fine foods’ from a showroom in London’s West End”.

“The East India Company today remains history’s most ominous warnings about the potential for the abuse of corporate power — and the insidious means by which the interests of shareholders can seemingly become those of the state. For, as recent American adventures in Iraq have shown, our world is far from post-imperial, and quite probably will never be.

Instead, the Empire is transforming itself into forms of global power that use campaign contributions and commercial lobbying, multinational finance systems and global markets, corporate influence and the predictive data harvesting of the new surveillance –capitalism rather than — or sometimes alongside — overt military conquest, occupation or direct economic domination to effect its ends.

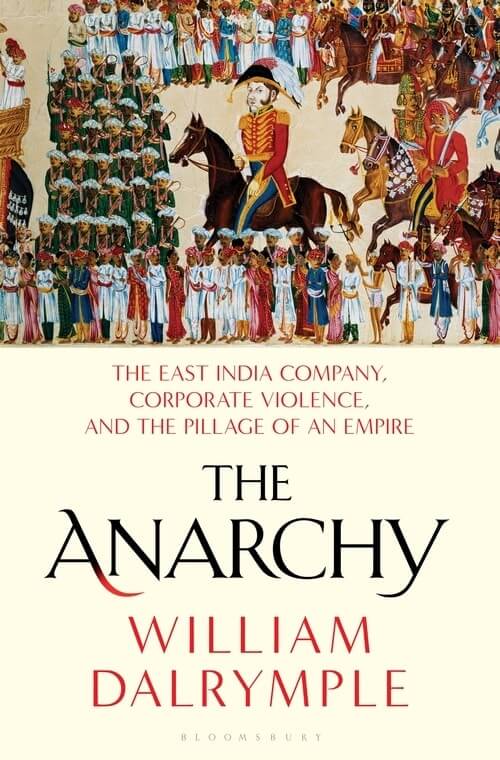

“Four hundred and twenty years after its founding, the story of the East India Company has never been more current,” Dalrymple writes in “The Anarchy – The East India Company, Corporate Violence, And The Pillage Of An Empire” (Bloomsbury).

To explain the “loot”, the Hindustani slang for plunder and one of the very first Indian words to enter the English language, the author graphically transports the reader to the 13th century Powis Castle, a craggy fort in the Welsh Marches, which houses the treasures that Robert Clive brought home from India.

“For Powis is simply awash with loot from India, room after room of imperial plunder extracted by the East India Company in the 18th century. There are more Mughal artefacts stacked in this private house in the Welsh countryside than are on display in any one place in India — even the National Museum in Delhi,” Dalrymple writes.

He then provides a fresh perspective.

“We still talk about the British conquering India, but that phrase disguises a more sinister reality. It was not the British government that began seizing great chunks in India in the mid-18th century, but a dangerously unregulated private company headquartered in one small office, five windows wide, in London, and managed in India by a violent, utterly ruthless and intermittently mentally unstable corporate predator — (Robert) Clive. India’s transition to colonialism took place under a for-profit corporation entirely for the purpose of enriching its investors,” the book says.

“The Company’s conquest of India almost certainly remains the supreme act of corporate violence in world history. For all the power wielded today by the world’s largest corporations — whether ExxonMobil, Walmart or Google — they are tame beasts compared with the ravaging territorial appetites of the militarised East India Company.”

The Company had been authorised by its founding charter to ‘wage war’ and had been using violence to gain its ends since it boarded and captured a Portuguese vessel on its maiden voyage in 1602. Moreover, it had controlled small areas since the 1630s.

Nevertheless, the defeat of Mughal emperor Shah Alam in 1765 “was really the moment that the East India Company ceased to be anything even distantly resembling a conventional trading corporation, dealing in silks and spices, and became something altogether much more unusual”.

“Within a few months, 250 company clerks, backed by the military force of 20,000 locally recruited Indian soldiers, had become the effective rulers of the richest Mughal provinces. An international corporation was in the process of transforming itself into an aggressive colonial power.”

By 1803, when its private army had grown to nearly 200,000 men, twice the size of the British army, “it had swiftly subdued or directly seized an entire subcontinent. Astonishingly, this took less than half a century. The first serious territorial conquests began in Bengal in 1756 (culminating in Robert Clive’s victory in the Battle of Plassey a year later); 47 years later, the Company’s reach extended as far north as the Mughal capital of Delhi and almost all of India south of that city was by then effectively ruled from a boardroom in the city of London. ‘What honour is left to us’ asked a Mughal official,’when we have to take orders from a handful of traders who have not yet learned to wash their bottoms’,” the book states.

As for Robert Clive, with a “good proportion of the loot of Bengal” going “directly’ into his pocket, he “returned to Britain with a personal fortune then valued at 234,000 pounds that made him the richest self-made man in Europe”. After Plassey, he transferred to the EIC Treasury “no less than 2.5 million pounds (262.5 million pounds today) seized from the defeated rulers of Bengal — unprecedented sums at the time”.

“No great sophistication was required. The entire contents of the Bengal Treasury were simply loaded into one hundred boats and floated down the Ganges from the Nawab of Bengal’s palace in Murshidabad to Fort William, the Company’s Calcutta headquarters. A portion of the proceeds was later spent rebuilding Powis,” the book states.

To this extent, the book has attempted to study the relationship between commercial and imperial power, as Dalrymple himself states.

“It has looked at how corporations can impact politics and vice versa. It has examined how power and money can corrupt, and the way commerce and colonisation have so often walked in lock-step. For Western imperialism and corporate capitalism were both at the same time, and both were to some extent the dragons’ teeth that spawned the modern world,” Dalrymple writes.

IANS – Vishnu Makhijani

Dalrymple's tome to perils of corporate power abuse

Reading Time: 4 minutes