I didn’t realise it until now.

The title of NGV International’s current temporary South Asian exhibition is problematic.

When I first read it, Visions of Paradise: Indian Court Paintings, it slid over me innocuously, as exactly the kind of title this exhibition of 17th, 18th and 19th century paintings – produced mostly in the princely courts of Rajasthan – would be given. I am, after all, accustomed to the grandiose, exotic titles under which South Asian culture is consistently packaged to a Western public.

But Visions of Paradise? Of course, there are paintings in the collection depicting the love-play of the romantic divine couple Krishna and Radha, paintings that show the worship of Shiva and the goddess Annapurna, visits of women to holy men and women of various sects. However, the exhibition displays these in their own separate sections. This vast and diverse collection of paintings is in the main rich depictions of highly ceremonial and symbolically weighted scenes of secular court life in the erstwhile states of Bikaner, Marwar (now Jodhpur), Jaipur, Kota and Mewar (now Udaipur).

And arguably, the sacred and profane, courtly and mystic, poetical and political aren’t discrete categories in South Asian art forms at all – they wind together comfortably, aesthetically, free from hard lines that we draw between them in our current denominationally-obsessed world.

So what is with the Visions of Paradise thing?

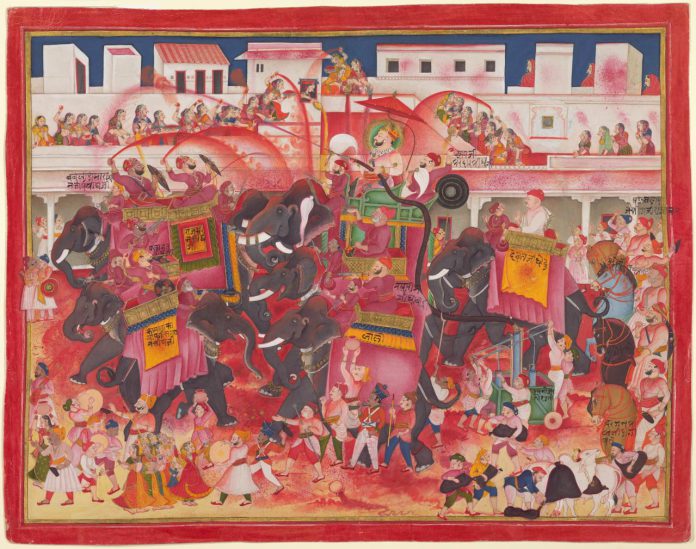

By now you might think I’m overthinking this. These paintings are undeniable treasures, gloriously vibrant, glowing down from the walls, a happy blending of Persian, Mughal Indian, and pre-Mughal Indian materials, techniques and visual vocabulary. They are made for intense looking – for poring over their incredible detail, their vast scope, in scenes of polo games, elephant fighting, alligator feeding, hunting, Diwali celebrations. For sighing with pleasure over the delicate lines and soft, gemmed colours of single figures of exquisitely costumed men and women, offering prayers, longing for lovers, sharing glances with a paramour or consort, looking down from a window, smoking a water pipe. For stepping back and enjoying the quirky, unsteady depictions of perspective, a technique taken by South Asian artists from their Western visitors and trading partners, and, with typical creativity, turned on its head and played with however they saw fit. For going in as close as you can without touching the centuries-old paper, and looking for the unexpected, a reward for those who take the time to do it: a tiny gold figure waving its arms from the pond that female musicians are assembled around, the vivid rage on the quarter-inch length face of a virahini (female mourning over separation from her lover), the vicious devouring of a deer by a falcon.

They are transportive in their beauty and vitality – visual windows to whole, complete, miniature worlds.

And yet, that title is important to interrogate. These paintings certainly are stylised works, offering us a splendid ideal, a politically and culturally crafted image of (male) power and sensuality. They are certainly the product of a vision. But Visions of Paradise obscures the historicity of these kingdoms, their individuality, the personalities of their rulers, the world that the works were produced in, and the modes of their production. It sounds like the title that 19th-century British colonial collectors would come up with for this exhibition.

I also wish that there was more creativity and imagination in the curation and display of these exhibitions, a desire to really open up this world that is constantly offered up as exotic and ‘other’, and consumed as such. The paintings are grouped into sections like “play”, “hunting”, “poetry”, “harem”, distinctions that aren’t useful, as I have said, to really getting into the heads of the premodern men and women that inhabited and ruled these courts. The informational panels are equally superficial, and perhaps even misleading – one thing I object to heavily is the distinction between ‘Mughal’ and ‘Indian’ art: once again, it’s a false one.

Go see the paintings, just for the pleasure of seeing them. Look at them closely, marvel at them, as the courtiers and rulers of their time would have done.

But I think they deserved more.

Paradise lost

When the title of an exhibition does little to capture the essence of the subject area

Reading Time: 4 minutes