World War I was a long and brutal military confrontation between the major powers of the early 20th century, fought across the trenches of Europe and in large swathes of Asia and Africa, resulting in the death of millions of hapless soldiers who became unwitting pawns in the great global “game”.

The four-year-long war that led to as many as 20 million dead and an equal number wounded ended on November 11, 1918, when an armistice was signed and a defeated Germany was compelled to accept closure. Over the last decade, there has been a spurt of interest among historians about the Great War; and the Indian contribution which remained relatively obscured has been brought back into focus. Undivided India, then a colony of the British Empire, contributed 1.5 million soldiers and non-combatants to this war and they served with distinction in all the major theatres. It is estimated that as many as 74,000 of them died in that war.

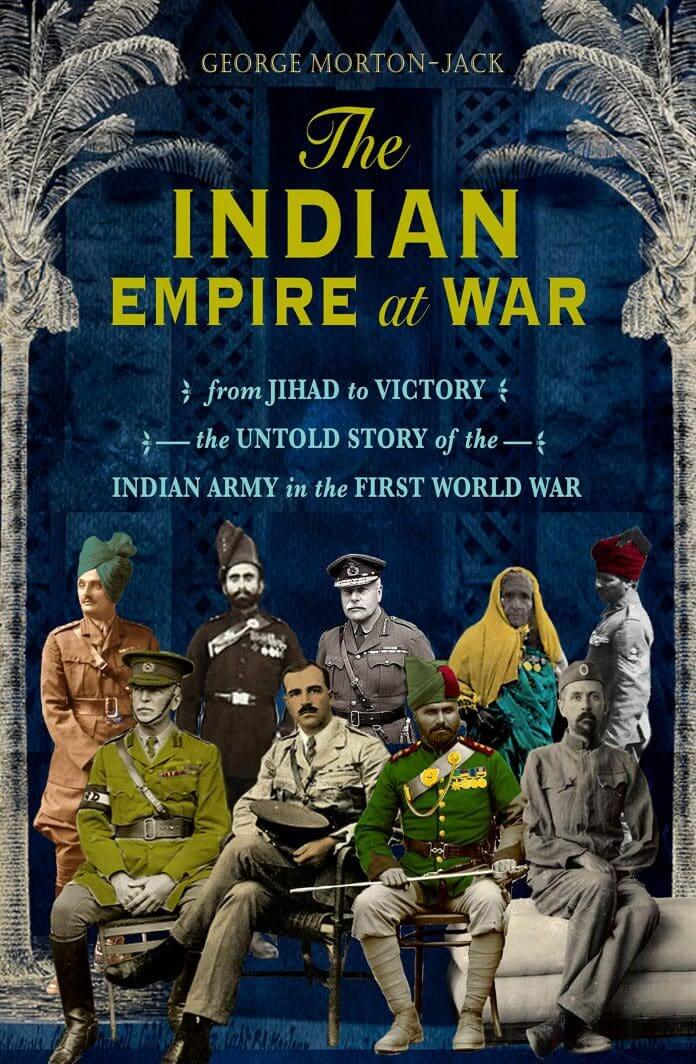

George Morton-Jack’s book The Indian Empire At War (Little, Brown, 2018) is among the more recent additions to this slim corpus on the Indian effort in the Great War and is both comprehensive and distinctive. The author points out, “This book is the first single narrative of it on all fronts, a global epic not only of the Indians’ part in the Allied victory over the Central Powers, but also of soldiers’ personal discoveries on their four-year odyssey.”‘

Neatly divided into six major chapters, the book provides the political context, beginning with the Delhi Durbar of 1911, in a lucid introductory chapter and the manner in which Herbert Asquith, then “Britain’s brandy-loving Prime Minister”, declared in Parliament on August 6, 1914: “We are unsheathing our sword in a just cause.”

But when they were swiftly recruited from different parts of British India to be shipped (like lambs to the slaughter) to distant lands in Europe – for many of these young men it was their first foray outside of their villages and small townships – they understood little of the complex politics about the War, intrigued about the “Jermuns”.

Morton-Jack writes “…the Indian ranks stoically suffered the Western Front’s rain and mud, cruelly catapulted by the fates into a war far from home that was never their own yet winning their fair share of VCs.” (As a contemporary aside, US President Donald Trump chose to avoid the rain and skip the centenary ceremony outside Paris on November 11, 2018.)

The VC (Victoria Cross) was awarded for the highest acts of gallantry in “the presence of the enemy” and this book empathetically records the incredible valour of the Indian “fauji” in the Great War. As the author recounts, in 1927, the Secretary of State at London’s India Office “favourably compared the Indian infantry in France to the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, ‘those whose valour was immortal'”.

However, this book is not only about the battlefield exploits of the Indian soldier but a multi-layered, rigorously researched and empathetically interpreted account of the Indian contribution to the Great War. The author’s objective of shining “a more filtered light on the Indian soldiers” is luminously met.

Pictures and maps embellish the value of this book and one of the more moving is that of an Indian cavalryman sharing his food with a local woman near Baghdad. Another is of a German officer standing over the body of a dead Indian soldier – posing for the “trophy” photograph.

Morton-Jack, to his credit, does not shy away from recording the cruel face of the colonial ruler and details the coercive methods used to recruit the reluctant tribal Indian. He notes that despite all the talk in London of “fighting the World War in defence of freedom”, the unfortunate experience of the Kuki (Assam) and Marri (Baluchistan) tribesmen – where hundreds were killed by British and Indian officers for resisting recruitment – “revealed that as colonial rulers the British had not changed their ugliest spots of colonial control from pre-1914 days”.

This is a splendid book and the author is to be commended for the manner in which he leavens the diligence of the researcher with the objectivity of the historian.

The Indian effort in WWI

C. UDAY BHASKAR reviews a new book that traces the footsteps of the Indian Army's 1.5 million men who fought for the Allies in 1914-18

Reading Time: 3 minutes