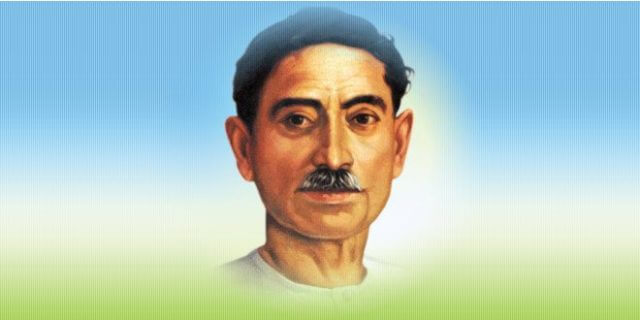

If you know the name of only one Hindi novelist, it is probably that of Munshi Premchand.

I recently stepped off a train at the New Delhi Railway Station and saw a picture of Premchand next to that of a muscle-bound body builder. It was at a book stall in Paharganj, where a copy of Premchand’s novel Seva Sadan lay on the ground next to a pamphlet called “Body Builder kaise bane (How to become a body builder)”. I tried to formulate a silly WhatsApp joke that seemed to be staring up at me.

Student: “Sir, how can I become a body builder?”

Hindi teacher: “Read Premchand every day!”

This week marks Premchand’s birth anniversary. That his work can still be found in the lanes of Paharganj 138 years after he was born is a testament to his enduring status as the father of modern Hindi literature. If you know the name of only one Hindi novelist, it is probably of Munshi Premchand. If you can name only one Hindi novel, it is probably Godaan.

So much has happened in Hindi literature in recent decades, but Premchand’s was the only literary face peering up from that book display. I wish there were more. Nevertheless, it’s still nice to see Premchand when walking about, and I purchased them both—the novel and the body builder’s guide.

The cover of this copy of Seva Sadan describes it as “an exploration of the reasons and consequences of a woman’s downfall”. The heroine is brought up in privilege, but after finding herself in an unhappy marriage, she leaves her husband and earns fame as a courtesan. This all takes place in Varanasi—the inner, seedy side of the city. Today, Varanasi is Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s constituency, and plans are underway to make Varanasi one of India’s smart cities. It has been suggested to me that Premchand’s novel has no relevance because Varanasi is going digital. The Paharganj bookseller disagrees, and so do today’s Hindi authors. It is my hope that in a few years, I might see a book such as Geeta Shree’s 2017 novel Haseenabad next to a body-builder. Her novel explores similar themes to Premchand’s, and studying his writing prepared me for reading hers.

My introduction to Premchand’s writing was his short story Thakur ka Kuan. It was part of the Hindi curriculum at the University of Texas. As such, it formed my introduction to literary registers of Hindi. It taught me what Hindi literature could look like—how a skilled Hindi writer uses style and symbolism, and how a Hindi reader can enjoy their effects. So I have a soft spot for this story, and I often assign it for my advanced Hindi students in Australia.

In his essay Sāhitya kā Uddeśya, Premchand argued that a writer’s obligation extends beyond entertainment, amusement and the description of heroes and heroines. He felt that literature should give voice to the problems of society, and should also be part of a solution to those problems. We see this voice in Thakur ka Kuan which, like much of his writing, explores the lives of the oppressed, impoverished and exploited people. It portrays the vicious effects of caste discrimination in pre-Independence India and lays bare the hypocrisy of upper-caste village landowners.

Premchand’s writing is relevant today, because it opens the door for authors such as Omprakash

Valmiki who write from the margins. Premchand taught me to read Hindi literature. For this, I am

grateful to Premchand and wish all readers good fortune on his birth anniversary.

Analysis of Premchand’s work has often focused on its content: What social ill is Premchand highlighting? How does he aim to evoke sympathy for those trapped in an unjust system? Gangi, the protagonist of Thakur ka Kuan, faces great injustice, and Premchand’s aim was to evoke sympathy for her plight. She cannot give her sick husband water from her well, because it has been spoiled by a dead animal. She is a Dalit, so she is prohibited from retrieving clean water from the nearby Thakur’s well. But she is desperate and decides to try anyway. She fumes against the greed and lechery of the high-caste people who shun Dalit women, and yet lust after them with greedy eyes. Premchand’s vivid description of Gangi approaching the well reminds us of the great physical danger that follows her not only in the Thakur’s district but after every step she takes in her village.

I have been questioned a few times on the rationale for having Australian students read a story like Thakur Ka Kuan. One Indian friend suggested that the story has lost its relevance, because, just as Varanasi is going digital, the problems Premchand depicts no longer plague India to the extent they did two generations ago.

This is not true, of course. Stories of oppression are always relevant in India and anywhere else. A more compelling critique of Premchand comes from the emergence of Dalit literature as a genre. Take, for example, Omprakash Valmiki’s criticism of Premchand’s portrayal of Dalit individuals. Premchand was born into a family of relative privilege. Omprakash Valmiki argued that Premchand viewed oppressed communities looking down from the top. That is, in his attempt to elicit sympathy for Dalit people, Premchand failed to show their continued struggle against an oppressive system. My students read also read sections of Omprakash’s famous autobiography Joothan. We do this not to compare, but simply read, and read critically.

Premchand’s writing is relevant today, because it opens the door for authors such as Omprakash Valmiki who write from the margins. Premchand taught me to read Hindi literature. Without him, I wouldn’t have read Omprakash’s autobiography. I wouldn’t have read Krishna Sobti’s magnificent recent novel Gujrat Pakistan se Gujrat Hindustan, or Geeta Shree’s Haseenabad. The list goes on, and fills my office bookshelves. For this, I am grateful to Premchand and wish all readers good fortune on his birth anniversary.

The author is lecturer in Hindi at La Trobe University (Melbourne, Australia)

The original article is published on The Print here.