With statistical supremacy, longevity, and a likeable humility, Roger Federer is unsurpassed

What makes an athlete great? Sports fans love to talk about numbers, but in a realm where passion supersedes logic, numbers can only tell so much of the story.

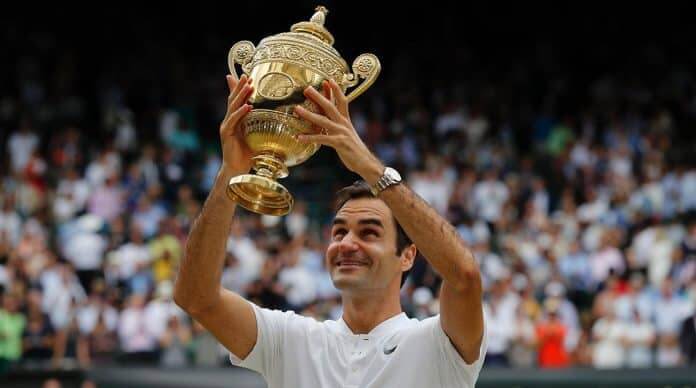

After all, even within the same sport, numbers can flatter to deceive – Adam Voges has the second-highest Test match average of all time, while the winner of a tennis match will often score fewer points than the loser. Quantifying greatness involves analysing more than mere statistical supremacy; it necessitates sustained excellence, widespread influence and, most importantly – and perhaps most elusively – the innate ability to both command and give respect. The conclusion of such an analysis? Unequivocally, Roger Federer stands alone as the greatest of them all.

Comparing athletes across eras, sporting codes, and between the genders is by its nature a road fraught with danger; in years gone by, Jordan, Ali and Pele were touted as the greatest ever in their time, and future athletes too will eventually enter the fray. Yet, there are flaws even amongst the most hallowed names: Jordan’s achievements were mainly domestic, and the shadow of LeBron James looms large; Ali’s numbers don’t rank him ahead of the other great pugilists; and Pele’s reign – in his sport alone – is challenged by the likes of Maradona and Messi.

There is little to separate Usain Bolt and Michael Phelps, perhaps the two greatest racers of all time. In Phelps’ case, his appeal wanes outside of the USA, while his two DUI offences – if not damaging to his legacy – are nevertheless relevant detractions. Meanwhile, Bolt’s is a sport where international competitions are held only once a year, and the pinnacle of the sport only once every four years. Although you would not discount Bolt’s sustained excellence, to compete only once a year on a competitive stage – and that too for a matter of seconds – is a different beast altogether to touring on the unforgivable ATP and Grand Slam schedule.

Sir Donald Bradman would reign supreme if this was an analysis of the greatest athlete amongst Test-playing nations; unfortunately, Australia’s greatest ever sportsman misses out due to the limited influence of cricket, particularly during his era. Unfortunately, if there is no room for the Don, then for the same reasons, Sachin Tendulkar must be refused entry to the club – in any case, while the Little Master easily meets each of the prescribed factors, Jacques Kallis was arguably the most valuable cricketer of Tendulkar’s generation. Others, too, would storm into any such discussion – Sir Vivian Richards was feared, loved, and dominated his opposition with a ferocity several decades ahead of his time.

In the tennis world, Serena Williams has more singles and doubles titles than Federer, but even while Serena’s dominance of the game demands respect, she does not readily give it out. Not easily forgotten are her attacks on then-world number one Dinara Safina in 2009, her physical threats to a linesperson during the 2009 US Open, and her unrelenting abuse of an umpire during the 2011 US Open final.

Then there is Federer. As far as numbers go, he is statistically the greatest tennis player of all time. Although Rod Laver and Margaret Court deserve honourable mentions, even during their time – perhaps primarily the fault of inferior technology – their influence was not so widespread. Meanwhile, Federer’s losing record to Nadal is a misnomer; a head-to-head record has rarely been used to assess greatness in tennis. Laver, for instance, had a losing record to fellow countryman Ken Rosewall, but there is no debate as to the greater of the two.

Federer’s sustained excellence is self-evident – over a 20-year career, he has played more than 1,300 matches, vanquished three generations of tennis players and owns almost every record in the game worth owning.

It is the respect that Federer shows – to the game, its fans, its officials, its history and its wider stakeholders – that is unparalleled.

A keen student of the game, Federer respects his peers as much as he respects those who have come before him, and it’s obvious that history means something to him; his now infamous tears upon being presented with the Australian Open trophy by Rod Laver in 2006 are evidence enough.

In the media, Federer conducts press conferences in three languages – English, Swiss German and German. Yet, despite being forced to answer the same questions for over a decade now, just as he does on court, Federer has more time than anyone else. Each question is met with a patient, considered response, and each journalist greeted with unassuming eye contact. To his fans, Federer is more generous than most.

Each year, in Federer’s corner at the Australian Open, sits an Australian couple, the parents of Peter Carter, one of Federer’s earliest and most influential coaches. Carter was killed in an accident on safari in 2002, and ever since that day, Federer, who was so distraught upon hearing the news that he ran bawling through the streets of Toronto, has extended an invitation to the Carters to watch him play.

The reason Federer transcends his contemporaries and his idols alike on any sporting arena is because as a human too, he excels.