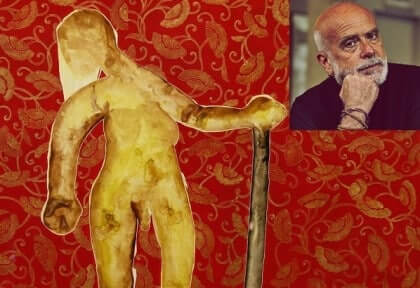

In his first Sydney exhibition, continuity of discontinuity remains the only truth for artist Francesco Clemente

Francesco Clemente came to India looking for reconciliation. As a young man in his twenties, he did not know anything about the nation and its culture when he arrived in Tamil Nadu. He had just married the avant-garde stage actress Alba Primiceri (seen here painted in her blood-red Comme de Garçons dress and a gold Indian bracelet that was the poster for Clemente’s 1999 Guggenheim show in New York).

Born in Naples, Italy in 1952, Francesco Clemente belongs to a generation that knows the importance of boredom and entertains it. Without boredom he feels, “you can have no new ideas”. He shuns all the limitations of labels and believes in a fragmented self and the gaps that separate different personas. For him, the most accurate description of our consciousness is “the continuity of discontinuity”. Change, to be precise.

His life has been a manifestation of these two primary beliefs and his paintings a witness to them. Before commencing his New York sojourn, the third-leg in his tripartite life after Italy and India, he ensured that he thoroughly studied and imbibed the Indian visual sensibility, both contemporary and traditional. He studied the forms and colours, political campaigns and movie posters, as well as the deities, shrines and frescoes in the temples of Tamil Nadu. The explicit sexuality and the physicality of the gods and goddesses became an inseparable part of his psyche and his paintings. He once told an interviewer: “The gods who left us thousands of years ago in Naples are still there in India.”

He had by then acquired an Indian eye and his work reflects the aesthetic of this perception as seen in his first exhibition in Sydney, Encampment, being shown at Carriageworks. Encampment includes six large-scale tents spread across 30,000 square feet of exhibition space. Clemente collaborated with chippa artisans (masters of block-printing technique) in Rajasthan over a period of three years. These tents feature Byzantine angels, real and allegorical figures, and self-portraits. While the interiors are hand painted in tempera (a painting medium consisting of coloured pigments mixed with water-soluble binder medium), the camouflage fabric of the exteriors is block-printed and embroidered by Rajasthani artists.

Each tent and its interiors unfold according to a theme. “You can see them as prehistoric caves, or mediaeval chapels,” Clemente says.

In his Devil’s Tent, heaven and hell are perfectly balanced, but the equilibrium can be tilted with minimal effort. Mephistopheles (a demon in German folklore) looks dapper in a hat and a monocle puffing away at a cigar, while the devil himself is an imperialist slave trader. In the label for the Angel’s Tent, Clemente writes, “The Devil is one and it is opaque. Angels are many. Today’s angels are very tired. Indifference wears one out more than hate. Angels are fragile and fall asleep all the time because they are content.” Inside the tent, one sees angels sunning themselves, lying under umbrellas with their wings drooped.

In the Taking Refuge Tent, predatory creatures are seated in the nirvana position, like the Buddha, cradling prey in their arms, hinting at the contradiction between spiritual teachings practised in isolation and the way in which the real world works. In his Museum Tent, Clemente explores the humorous side of loss.

“No one knows what the meaning of a museum really is,” he says. “Everyone agrees that anything found in a museum is dead to life. A personal museum is a collection of all the selves one has been, a graveyard of all previous personal delusions.”

This thought, coupled with his nomadic and transitory experiences, is also continued in his other works. Exhibited alongside the tents are four archaic looking, vertical sculptures – Earth, Moon, Sun and Hunger – with references to contemporary life. Also featured is a collection of 19 erotic paintings drawing on Mughal miniature painting traditions, titled No Mud, No Lotus. These water-colour paintings blend Indian and Western European imageries to create a hybrid visual. In India, the artist explains, “I found a place that was utterly contemporary and with the same vitality and drive that I knew of in the West, but in completely alternative terms.”

Clemente came to prominence in the mid-1970s and is widely recognised as one of the most remarkable and evocative artists working today. His inspiration is as varied as the company he kept. The thoughts of William Blake, Allen Ginsberg, J. Krishnamurti, works of his contemporaries Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, his nomadic life and its vibrancy, have all had considerable influence on him.

“Every single moment of the unfolding experience of the work is just a pretext to move on, to move forward from that moment,” he explains. “It’s never supposed to be a beginning of an ending; it’s supposed to be a transition.”

His New York dealer, Mary Boone, differentiates him from the other artists of his time.

“A lot of artists cower in the face of a new aesthetic. They try to conform with what they think is popular now. Francesco continues to make his own work. He’s not interested in trends.”

He doesn’t fear being left out of the conversation, she says: he starts his own conversations.