He may have ended up as a mere footnote in the annals of Hindi cinema with just one flop film to his account, had his mentor been hungry for money. As a result, connoisseurs would have been deprived of exquisite qawwalis, elegant love songs, and aesthetic compositions showcasing the immortal words of Tulsidas and Meera.

And for 21st-century Bollywood fans, would Hrithik Roshan have emerged, had his grandfather abandoned his ambitions?

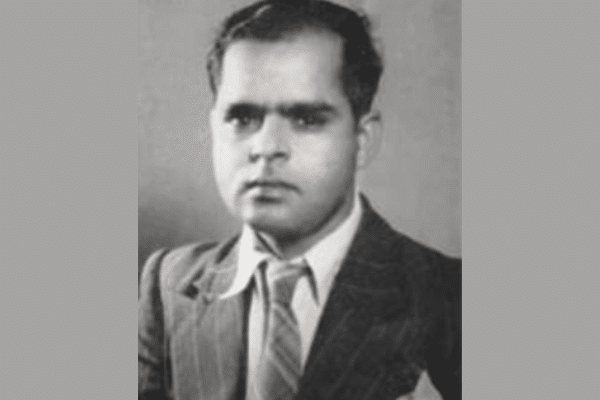

Roshan (1917-67), born Roshan Lal Nagrath on July 14 in Gujranwala (undivided Punjab), spent just a third of his tragically short life in the film industry. However, during this span, he spun pure gold with his trademark classical music-based melodies. A leading music director, who also played a key role in his life, likened his music to honey dripping from a honeycomb.

Roshan deservedly was deemed to be the foremost exponent of the filmi qawwali, but his oeuvre was not limited to this form – it appears in just half a dozen of his 67 films.

Songs written in other styles include Khayalon Mein Kisi Ke (Bawre Nain 1951), Salaam-e-hasrat Qabool Kar Lo (Babar, 1960), Jo Vada Kiya Vo Nibhana Padega (Taj Mahal, 1963), Hum Intezar Karenge (Bahu Begum, 1967) and many others.

Above all, there is the bhajan Ae ri main to prem diwani (Naubahar, 1952) and Man Re Tu Kaahe Na Dheer Dhare (Chitralekha, 1964), skilfully adapted by Sahir Ludhianvi from Tulsidas’ Mana Tu Kahe Na Dheer Dharat Ab..., rendered sublimely by Mohammad Rafi.

Then, gauge how Roshan imbued a spiritual feel to Chhupa Lo Yun Dil Mein from Mamta, aided by the dulcet tones of Hemant Kumar and Lata Mangeshkar, and Majrooh Sultanpuri’s poetry.

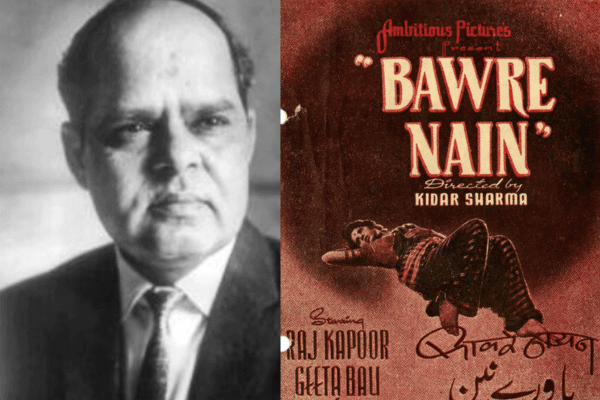

But, as mentioned, all this would have never come to pass without the trust shown by legendary director, producer, lyricist and screenwriter Kidar Nath Sharma, who had spotted Roshan, then working with AIR Delhi as an esraj player, way back in 1945 and offered him a career in the film industry.

Roshan had initially refused, but later approached Sharma in 1949 when he moved to Bombay. Sharma offered him a chance to compose for his Neki Aur Badi (1949), convincing his own regular composer Snehal Bhatkar to sit it out. The latter obliged.

The film flopped and a distraught and disheartened Roshan told Sharma that he was no good and wanted to commit suicide. The filmmaker heard him patiently and asked him which Bombay beach he would prefer to do away with himself.

Then, on a serious note, he went on to say that if Roshan would defer his plans, he would offer him another chance in his forthcoming film.

During the film’s making, an influential distributor came to meet Sharma and in Roshan’s presence, promised him a large amount if only he would drop the music composer. Roshan went to another room and began sobbing, telling Sharma, who followed him, to accept the offer. Sharma, however, went back to his office and said no.

Bawre Nain (1951), with songs like Teri Duniya Mein Dil Lagta Nahi and Khayalon Mein, was a hit and was the start of Roshan’s musical journey.

Sharma was more patient than Anil Biswas, who took direct action when Roshan began crying. After failing to calm him down, he gave him a slap, wondering how he would succeed this way. It was later Biswas who likened his music to dripping honey.

Roshan, whose music reflected his classical training, also had a penchant for knowing when to let his tune yield to the lyrics or the singer. His most famous qawwali, Na To Karvan Ki Talash Hai is a prime example and so is the same film’s Maine Shayad Tumhe Pehle Bhi.

There was much more music left in Roshan when he succumbed to a heart attack in 1967.

READ MORE: Bharat Bhushan: Hindi cinema’s beloved lovelorn poet