It is a visual language with which we are almost all familiar. It’s cold and snowing outside, but inside, next to a crackling fire, it’s warm and cosy. The tree is a deep green, festooned with fairy lights, glinting off the wrapping of the presents below. There is hot chocolate and sugar cookies and eggnog and candy canes, and the only things that can be heard are carols and the joyous laughter of our nearest and dearest.

This image of Christmas is, of course, vastly different to what we usually experience in Australia – extreme heat, seafood platters, white wine in the sun – but it is still one with which we are very familiar. It’s present in all our retail settings, with their fake snow and holly and Santas sweating in their suits.

And of course, it’s all over our media, in the increasingly ubiquitous Christmas romantic comedy film.

Counting down to Christmas

Christmas movies have a long history, dating back to the 1898 short film Santa Claus, but the Christmas rom-com really hit its stride in the 21st century.

Better decisions start with better information.

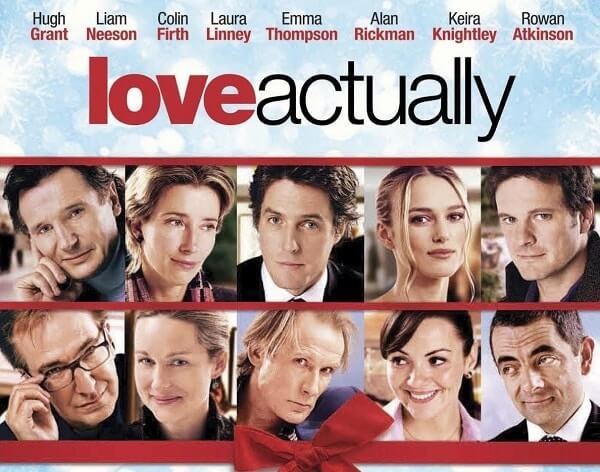

Love Actually (2003), an ensemble film featuring multiple intertwined stories, is perhaps the best-known example. However, in terms of sheer quantity, it is difficult to look past the company that has made Christmas their core business: Hallmark.

Since 2009, the Hallmark Channel have run a seasonal block of programming called Countdown to Christmas, central to which are their Hallmark Christmas movies. Countdown to Christmas has become increasingly extravagant: in 2021, it began on October 22, and featured a total of forty new movies, along with a (very) large number from previous years.

While Hallmark Christmas movies have been a cultural touchstone for many years in North America, that hasn’t been the case to the same extent in Australia, because we haven’t had widespread access to the flood of programming.

However, the advent and popularity of Netflix’s Hallmark-style Christmas movies, beginning with A Christmas Prince and Christmas Inheritance in 2017, have led to a growing familiarity and engagement with the Christmas romance genre from local audiences.

As a result, after many years with a dearth of local Christmas programming, Stan released A Sunburnt Christmas, their first Australian Christmas original film, a rom-com called Christmas on the Farm, which premiered on 1 December 2020.

Christmas on the Farm is missing a key ingredient of the Hallmark Christmas romance: snow (in the Hallmark universe, the characters “can’t be waiting for the snow, there has to be snow”). However, it boasts a screenwriter with Hallmark credentials in Jennifer Notas Shapiro, and draws on plenty of other tropes of the Christmas rom-com.

What makes a Christmas rom-com?

Hallmark has a reputation for conservatism, and we cannot fail to note that for many years, their movies featured exclusively straight, white, middle-class characters falling in love (although they are slowly beginning to diversity their casts).

It is perhaps surprising, then, that Christmas rom-coms do not tend to be particularly religious. Instead, as S Brent Rodriguez-Plate argues, there’s a more secular reason for the season underpinning these films – “the power of family, true love, the meaning of home or the reconciliation of relationships”.

Christmas rom-coms thus have a particular aesthetic (snow, mistletoe, ugly-but-snuggly jumpers), and a particular set of core values: family, community, selflessness, kindness, love. They’re rarely overtly supernatural, but the Christmas setting often gives rise to a little bit of “Christmas magic” or a “Christmas miracle”, which pushes our protagonists towards embracing these values.

As a result, there are some very common plots, settings, and themes in the Christmas rom-com.

Home for the holidays

This plot is Hallmark’s bread and butter. One of our protagonists – usually the heroine – returns home for the holidays. This is often against her will: she’s usually a city-dwelling career woman, leaving behind a similarly career-driven boyfriend.

But going home for Christmas reveals to her that although she might be successful, she hasn’t been happy. With the help of family and/or community and almost always a handsome hometown hunk (usually dressed in flannel), she learns to slow down and embrace what really matters to her.

Small towns

Our heroine is almost exclusively returning home to a small town, often with a Christmassy name and one or more struggling local businesses – a bakery, an inn, a Christmas tree farm.

She must learn that work does not bring her joy, and that she needs to slow down and take stock. However, she nearly always finds herself using her corporate skills to re-energise and revive these businesses. For films which make it clear that we should not dream of labour, a surprising amount of attention is paid to stimulating the economy of small towns.

Christmas kingdoms

If our heroine is not going home for the holidays, she might find herself in a small, ambiguously European and unambiguously Christmassy kingdom. There, she’ll have a run-in with some local royalty, with whom she’ll swiftly fall in love.

Netflix has leaned into this plot extensively in their Christmas rom-coms – it’s the foundation of both the Christmas Prince (2017-19) and Princess Switch (2018-21) trilogies.

No Grinches allowed

This is arguably the defining characteristic of Christmas rom-coms: they are sincere. Any cynicism towards the season is swiftly quashed. It is only by embracing the genre’s key values that the happy ending of the rom-com can be reached. Our protagonists must fall in love not only with each other, but also with Christmas.

A happy ending

Christmas rom-coms always end happily, with our central couple in love and everyone having a very merry Christmas. There is a familiar pattern to them – one does not watch these films to be surprised.

Like many of the trappings of Christmas, watching these movies is a holiday ritual for many people, as comforting as putting on a Christmas jumper. They’re films to snuggle into, secure in the notion that for now, all’s right in the world.

This article was written by who is a Lecturer in Writing, Literature and Culture, at Deakin University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read More: Burnout: How to take care of yourself before the holidays start