One of my earliest and fondest memories is sitting, half-sprawled out on the couch, clumsily pushing my freshly oiled, unshorn locks out of my face to make way for the aeroplane spoon full of dahl and dahi (yoghurt) that’s set to make a landing in my mouth. Being the restless toddler I am, I wriggle around in glee and giggle as the spoon makes a safe landing, delivering the earthy flavours I’d been anticipating. A gentle hand, armed with a damp towel, gently caresses the excess food off my face – collateral damage from all the wriggling – and my silver-haired Naniji (maternal grandmother) continues to patiently spoon-feed me while humming “Aukhi Gadhi Na Dekhan Deyi” (a Shabad/verse of Sikh holy scripture). I think that’s the first Shabad I ever learnt the melody of and it wasn’t till later on in life that I learnt from my Mum, who was shocked to randomly hear me singing it, that it was one of my Naniji’s favourites.

Fast forward a couple of years to my next best childhood memory. The phone rings, blaring through the empty corridors. I was playing in the living room when I hear my Nana Ji’s (maternal grandfather) voice bellow out from his room.

“Nikki! (Little one)” he called out to me.

I sprinted to his room like a soldier called to attention.

“Phone le ke aa,” he instructed. (Bring the phone here).

I looked at him puzzled. I’d only ever heard adults, like my Uncle and Aunties, answer the phone in English. My Nanaji has never spoken English, I thought to myself. I tried to explain but he ushered me out to fetch it.

I come back, phone in hand, but still hesitant to hand it over.

Quick as a flash of lightning, my Nanaji (who, mind you, hadn’t moved from the edge of his bed the whole time) grabs his walking stick and uses the hooked end to pull me in towards him. He plucks the phone from my hand and answers.

“Hello, Gill speaking,” he guffawed through the receiver.

My jaw dropped in disbelief as he carried out a conversation. He looked at me and chuckled cheekily before handing me the phone to put back.

When my mum arrived later that day I asked her, “Did you know Nanaji can speak English?”

She laughed and nodded.

That’s when I realised my grandparents were so much cooler than I could ever have imagined.

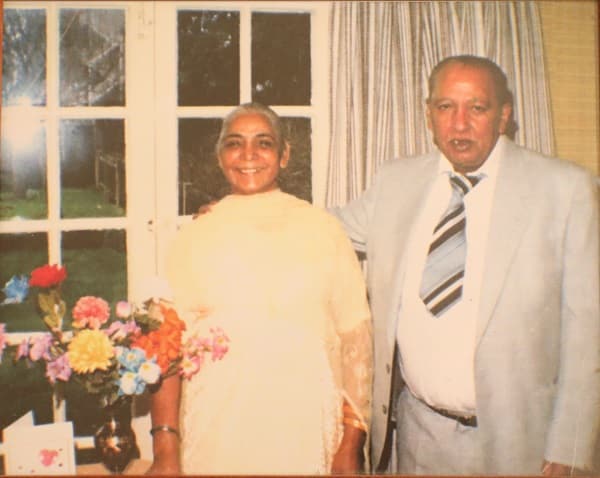

Both my grandparents were immigrants to Australia but, prior to that, were also immigrants to England and Singapore. My Nanaji was a WWII veteran who later worked in construction and the taxi industry. It turns out that, while he could speak English, he couldn’t read or write so he’d wake up early to memorise road routes after sussing them out with his English-literate children.

Contrarily, my Naniji couldn’t speak English but she always managed to find work – whether that was sewing, catering or delivering newspapers – to provide for her 6 children.

These are details about their lives that I, unfortunately, didn’t learn from them. My grandparents passed away when I was quite young but I never felt an absence of elder-presence/mentorship because of a concept in my community known as Sat Sangat (congregation of the local Sikh community). Many of the memories that I made with my grandparents took place amongst the Sangat, usually at a Gurudwara (Sikh Temple) or an Akhand Paath (prayers at people’s houses). It was the company that kept them the happiest. So, even after their passing, I found that elder-support from within my community.

Elders play an intrinsically important part in the Sat Sangat from teaching at Punjabi school, to doing sewa (selfless service) in the community and preparing Langar (food from the community kitchen). Essentially, they’re the glue that binds the congregation together with their knowledge and dedication to passing along religious consciousness/traditions. I, for one, would never have learnt Kirtan (devotional music) or Gurmukhi (Punjabi script) without their patience, presence and nurturing nods.

In turn, the Sangat plays a huge role in the lives of our elders, especially those like my grandparents who migrated from India to a foreign land. The Sangat provides a safe space for them to come for support, company, prayers, peace and guidance. In this way the Gurudwara, and the Sangat, become not just parts of a place of worship but also social and recreational institutions for elders to rebuild lost or faded social connections. It also provides ample opportunity for intergenerational bonding time. Aside from the social aspect, Sangat-led organisations also provide resources and volunteer-run programs like: Sikh Youth Australia’s Culture Care Clinics (which offer free health checks), Kathas (seminars) on Sikhism and even getting elders involved in more mainstream events like ‘Clean Up Australia Day’ by encouraging the community to come out together.

I’ll always be grateful for the presence of Sikh elders in my life because they always remind me of what I admire most about my background: the history, the values and the drive to always give back. Without the roots that these elders provide, I’d never get to see the awe-inspiring work the Sangat gets up to like cooking meals for those in need when COVID isolation hit or heading to the NSW South Coast to help those affected by the bushfires.

Our elders are the people who provided us with the opportunity to live in Australia while preserving the values of Sewa (selfless service) and Vand Chakna (sharing what you have) to the point where the following generations continue to do so and I will be forever grateful to them for it.

Young journalist Simran Gill’s story is part of a project entitled Stories of Filial Piety, featuring the lives of culturally diverse families in Sydney. Created by independent curator/producer Kevin Bathman, the series aims to explore the disconnect between Asian collectivist principles and Western individualist values, as well as provide insights into how Eastern traditions sometimes need to be adapted to suit Western practicalities.

Three independent filmmakers bring the stories alive on screen.

In Ana Tiwary’s film Filial Piety: The Chowdhury Family, one family describes what it is like to have three generations living together under one roof.

The project is funded by the City of Sydney’s Matching Grants program with support from The Centre for Social Justice and Inclusion, University of Technology Sydney and Diversity Arts Australia.

READ ALSO: Migrant grandparents who care for their kids