There are many people who make repeated mistakes – repeated identical mistakes – but are not dumb!

How is this possible?

Let me explain by way of example.

Like in every household, you probably have a place at your home where you place your keys. One day, decide to put your keys in a different place. Almost guaranteed for several consecutive days, you will go to the original place to find your keys – not the new place. While doing this you may suddenly remember that you have moved them to a new place. Most people, not understanding the nature of visual memory, will tell themselves that they are dumb. “How stupid of me to forget!”

How can educators and parents understand the nature of mistakes so that they know how to attribute the correct cause?

Students and adults who anchor what they do in their visual memory will find that they can make repeated identical mistakes. Similarly, people told to read when they favour auditory processes can make repeated mistakes.

However, you can be absolutely certain that the person who made the errors has not reduced their IQ. In other words, people who are very bright, can make repeated identical mistakes.

So how does this play out in education?

An example comes from early literacy.

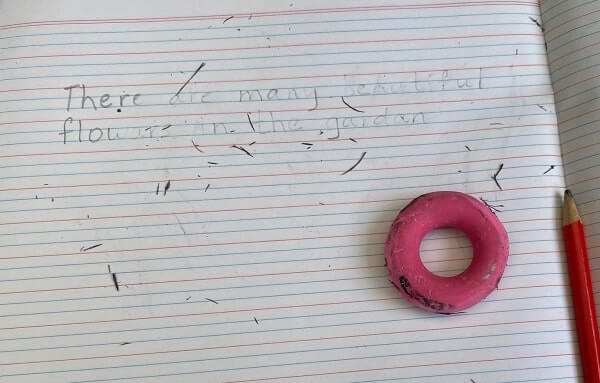

Very young bright learners, with strong visual memory, may well look at the shape of words when they read, rather than use a process of sounding out. What can happen with these learners is that the word that they “read” is anchored with the visual cue: the actual shape of the letters. This means that a similar looking word may well be replaced by the correct word. For example, the word “end” and “ant” have similar visual forms. So, a missed pronunciation on the first “reading” can mean the child makes repeated identical errors whenever they come across the word “end” reading it as “ant”.

Well-meaning parents and teachers who notice the error may say to the child, “Sound the word out.” However, a poor understanding of the nature of memory and how we anchor our learning in visual forms, means that the solution sought could be irrelevant to the learner. What is required is for the child to re-learn what they see. Instead of “sounding out”, what they might really need is flash cards and a process of practise to anchor the written word with the correct visual cue.

Understanding this is important to also understanding how adults learn.

It is highly likely that employees in the workplace can make repeated mistakes, particularly with respect to very detailed work. However, they may have been chosen for their intelligence. Here, either the nature of the work does not match the way they anchor what they learn, or the way they were trained does not link with the way they learn.

This is also important in the context of close personal relationships.

One of the things I observe is that people who are close can become stuck in patterns of behaviour that misunderstand the nature of how others learn.

Some people learn effectively when they read messages. For them, text and email are forms of communication they can relate to. However, others relate less to text and more to tone and feelings. In a string of messages, they relate to the feelings in the last sentence and miss the earlier detail. Others still relate extremely well to what they hear: the spoken word.

Understanding this is crucial to negotiating the complexity of close relationships. A person might say to their partner, “But I told you – didn’t you read the message I sent?” Their partner may well have read the message, but it didn’t have the same effect in their recall as this same communication would have if it was spoken.

This understanding is crucial in classrooms, the boardroom, and the home.

People are not dumb because they didn’t understand.

People are not dumb if the way they learn does not match the communication they receive.

People are not dumb if they need to say something out loud, to activate their auditory working memory, in order to understand what they need to do.

People are not dumb if they make repeated mistakes based on visual cues. After all, who hasn’t walked into a room and wondered why they are there? Nearly every person alive can relate to this. This does not mean they are experiencing memory loss, nor does it mean they are stupid. What it does mean is that standing in a room gives visual cues or context that can override what they had intended to do. This is a normal healthy cognitive process.

So, whether we are parents, educators, people in business, government or institutions, we need to start to understand how we – and others around us – learn. We need to continually interrogate the way we communicate, the way we teach, the way we train and the way we ourselves learn best, to understand how others learn best.

In this journey there is a crucial stance to take: assume that intelligence doesn’t vaporise when people make what appear to be repeated mistakes. Rather, ask yourself what you could do differently?

READ ALSO: There is no such thing as a “lazy” child