After months of holding out, Australia has at last joined other members of the World Trade Organisation in backing a waiver of patents and other intellectual property rights on vaccines, treatments, diagnostic tests and devices needed to fight COVID-19.

The organisation’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) requires WTO members to provide patent protection of at least 20 years for new inventions along with a slew of other intellectual property rights.

These rules make it difficult or impossible for developing nations to provide COVID-19 medical products, even where it would be straightforward to manufacture them.

TRIPS provides for exemptions, but the provisions are onerous and time-consuming. They apply only to patents, and don’t free up the rights to the information about the manufacturing process needed to make the treatments.

India and South Africa proposed the so-called TRIPS waiver in October 2020. Later revised and sponsored by more countries, it would have enabled developing nations to manufacture diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines for COVID-19 during the pandemic without fear of legal action.

The United States, home to some of the world’s biggest pharmaceutical companies, was at first hesitant until President Joe Biden backed a waiver — albeit limited to vaccines — in May.

Australia waited for the US, then waited

Australia held out longer than the US, even though US companies had more at stake. But unless Australia and other wealthy nations do more to merely vote for the waiver, “grotesque” vaccination gaps are set to continue for years to come.

Trade Minister Dan Tehan came out in support of the waiver at a meeting with several community organisations last Tuesday. He confirmed Australia’s changed stance in comments to The Guardian the following day.

The shift raises the chances of the waiver proposal getting through, boosting the global supply of vaccines, treatments and testing kits — a move that would benefit every nation afflicted by supply shortages, including Australia.

More than 100 of the WTO’s 164 member nations support it. But there are still wealthy nations holding out — including Canada, Japan, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the European Union.

Why the world urgently needs a waiver

COVAX, the global program for distributing vaccines equitably, originally intended to deliver two billion doses of vaccine by the end of 2021. So far, it has delivered less than 260 million.

On September 8, it revised its forecast to only 1.4 billion doses during 2021.

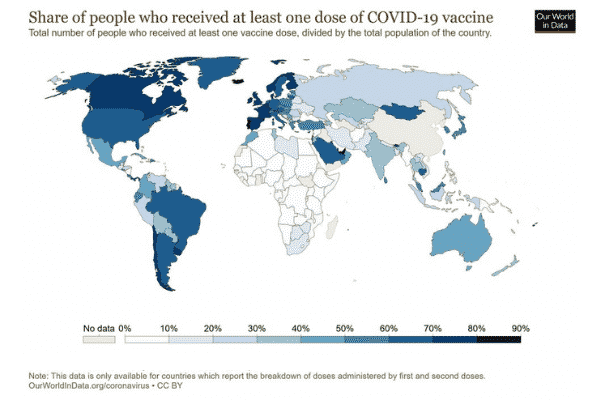

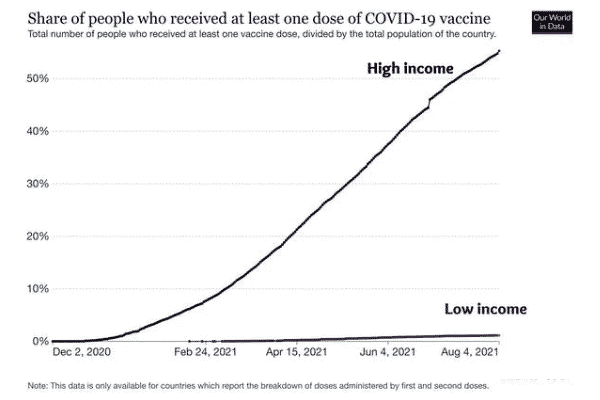

The World Health Organisation says less than 20% of the doses administered have gone to low and lower middle income countries, and while high-income countries have on average administered 100 doses for each 100 people, low-income countries have only managed 1.5 doses for each 100 people.

Underlying the problem has been a global undersupply made worse by a mere handful of companies holding the exclusive rights to manufacture the vaccines and the right to keep other companies out.

Pfizer and Moderna have so far declined requests to enter into voluntary licensing agreements with low and middle-income countries.

Unless rich countries including Australia support efforts to expand the global supply, many countries won’t achieve widespread vaccination coverage until at least 2023.

Variants emerging in areas of unvaccinated regions in the meantime could threaten the progress of the whole world in bringing the pandemic to an end.

Australia’s stance is complicated

In a letter to community organisations in August, trade minister Tehan indicated that while the Australian government was “focused on progressing discussions” in the World Trade Organisation, it saw voluntary mechanisms as the best chance for delivering broad access to COVID-19 vaccines.

The letter suggested that a scarcity of raw materials and lack of manufacturing capacity were the chief barriers to increasing vaccine production. It also pointed to the key role of intellectual property protections in encouraging the development of new vaccines and tests and treatments.

Right now there is probably little risk a TRIPS waiver would undermine the incentives needed to develop vaccines and drugs. There is an awful lot of money to be made from the well-off countries that would keep patents in place.

And the development of COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics and testing kits has been underpinned by huge injections of public funding that are unlikely to dry up.

Shortages of inputs are certainly part of the problem, although these are themselves partly created by intellectual property rights that limit the number of companies with rights to provide those inputs.

One example is the bioreactor bags used to mix cell cultures and gasses in vaccine manufacturing. They are produced by a small number of companies and heavily protected by patents. Waiving those patents could help end shortages.

While manufacturing capacity most certainly does need to be increased, there is a lot of it in less-developed countries such as Brazil, India and South Africa.

What matters is what Australia does next

The trade minister’s words have to be matched by actions at the World Trade Organisation. Unless Australia gets fully behind the TRIPS waiver in the negotiations set to climax in October, it mightn’t get up.

The head of the World Health Organisation has described the inequities in access to COVID-19 vaccines as “grotesque”. They are being made worse by hold-ups in allowing more countries to manufacture vaccines themselves.

The article first appeared in The Conversation, you can read it here.

READ ALSO: Home vaccination program for people who are housebound

Link up with us!

Indian Link News website: Save our website as a bookmark

Indian Link E-Newsletter: Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter

Indian Link Newspaper: Click here to read our e-paper

Indian Link app: Download our app from Apple’s App Store or Google Play and subscribe to the alerts

Facebook: facebook.com/IndianLinkAustralia

Twitter: @indian_link

Instagram: @indianlink

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/IndianLinkMediaGroup