The East of India – Forgotten trade with Australia exhibition explores early links between the two countries, as well as current ones, writes Lena Peacock

Although today’s links between India and Australia, including the often cited ” cricket, curry and commonwealth,” are clearly evident, what isn’t as well known is a much earlier link. Without India’s trade, Australia’s history could have been a very different story. The early Australian colonies needed nearby India, to both grow, as well as survive. East of India – Forgotten trade with Australia at the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) looks at these links, as well as modern-day ties between the two countries. And all of this is accentuated by the light show on the roof of the ANMM as part of Vivid Sydney.

“Many Australians are unaware that Australia has been trading with India for over 200 years,” says Exhibition Curator Dr Nigel Erskine. “Quite simply, those early connections with India were crucial to the growth and survival of colonial Australia”.

The exhibition consists of over 300 objects, ranging from artworks, coins, textiles and more, from 15 different lending institutions across Australia and London, including the British Museum.

The exhibition hones in on the “links between Australia and India from the 1790s onward and documents how integral the supply of Indian goods was to the fledgling colony,” Erskine told Indian Link. “Rice, livestock, clothing, shoes, soap, textiles and many other household goods were shipped to Sydney from India”. The exhibition also looks at what Erskine describes as “some key Indian leaders such as Tipu Sultan of Mysore and Rani of Jhansi,” and the East India Company’s rise and dominance from the 16th century to its decline in 1857. In addition to this, the stories of everyday Indians who came to live in Australia, and a contemporary short film in which, Indian Australians reflect on their culture, identity and what it means to be Indian Australian today, are also exhibited.

Erskine states that “we are now much more aware of the scale of the trade and its influence on Australia. From archival research we know of 24 vessels wrecked enroute from Sydney to India between 1797 and 1849”.

Indian Link chatted to Michelle Linder, Curator Special Projects at ANMM to find out more about the colony of New South Wales, and just how crucial India was for it. A lot centered on the fact that a voyage from Britain to Sydney took around six months, yet it only took around six weeks from India. It also didn’t help that incorrect assumptions were made about Sydney based on James Cook’s eight day stay in Botany, which happened to be a whole 18 years earlier.

“Governor Phillip soon discovered that the land was far from fertile as attempts to grow crops failed,” said Linder. “As a result, the colony was totally dependent on the supplies it brought out with it. As these dwindled, the situation of the settlement became desperate and when the supply ship HMS Guardian struck an iceberg south of the Cape of Good Hope, the colony was in real trouble,” she explained to Indian Link. “The accident to the Guardian changed official policy, and thereafter the colony was encouraged to trade with India”. Britain was still used as a major source of supplies, but trade with India became “increasingly important, particularly after the East India Company lost its monopoly on Indian trade in 1813,” continued Linder.

On the opening night of East of India on May 29th, Kevin Sumption, Director, ANMM, described the exhibition as “sumptuous,” and explained that it took over three years of research to pull the exhibition together. The exhibition was officially opened by Biren Nanda, High Commissioner of India, who spoke of the exhibition as being a “Timely reminder of our connections [between Australia and India] and a reminder that the first settlers had an experience of India”. He went on to explain that “in times of need Australia looked to India for help,” such as during first settlement, and “most importantly, for rum”. Nanda also explained the “increasingly robust ties” between the two countries, which has strengthened over the past few decades.

“It is fascinating to learn the history of contact between Australia and Asia, going back to the days of the spice trade” said visitor Sue Spence of the exhibition.

One of the key pieces of the exhibition is the Bejewelled sword of the Indian ruler of Mysore Tipu Sultan, killed by East India Company forces at the battle of Seringapatam in 1799. This piece is significant because it belonged to Tipu Sultan, ruler of Mysore who was killed at the battle of Seringapatam in 1799. Erskine explained to Indian Link that “Tipu’s story highlights the stiff resistance to the East India Company’s (and later, British) encroachment on Indian territory”. He went on to further explain that “he is a symbol of Indian tenacity which ultimately leads to Indian Independence in 1947”. This piece, which has Koranic inscriptions on it, has never been exhibited outside of Europe before, so it’s a great chance to see the piece. The hilt is covered with Tipu’s tiger-stripe emblem and two of the tiger-head terminals have jewelled (Moonstone) eyes. This piece is not to be missed.

Linder explains that the other pieces of note from the exhibition, includes Two Mughal miniatures paintings from the Art Gallery of NSW, a detailed panorama of Calcutta by artist Jacob Janssen, dated about 1830, and Tree of Life, a handpainted cotton hanging, made in India for the English market in 1810.

Also of note is an evening dress made from Bengal muslin for Anna King, the wife of Governor King. Linder told us that “this is one of the oldest surviving examples of clothing worn in colonial Sydney, from the collection of the National Trust of Australia”. It shows how casual colonial Australian dress was, especially when compared to examples from this time in England.

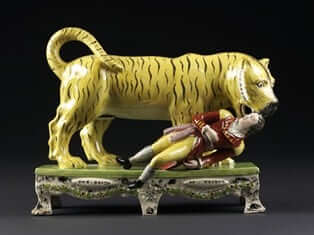

And the most bizarre object on display? A ceramic figurine showing the death of Lieutenant Hugh Munro by a Bengal Tiger. Tipu Sultan called himself the Tiger of Mysore and was so amused by his death, that he had a life sized automaton made to entertain him. It even roared like a tiger. The figurine reflects the unfortunate celebrity associated with Munro’s death, and is extremely kitsch.

The exhibition carefully leads the viewer through the displays, with plenty of information panels to give context to the objects. The use of numerous red panels and some Indian architectural elements helps to effectively tie the exhibition together.

The inclusion of the contemporary film and audio recordings are also nice touches. Unfortunately, the sound of the film made it a bit difficult to hear the recordings, as they share a common wall between the cinema space and the seated audio recording area. The recordings were of local Indian actors from Nautanki Theatre and Abhinay School of Performing Arts, who perform readings of testimony given by Indian servants who worked in Australia in 1819.

“These rare accounts enable voices of Indian workers, who were in Sydney in the 19th century to be heard by visitors,” explained Linder. They focus on a special inquiry about their complaints to Governor Macquarie. The ANMM makes a comparison between these Indian workers’ contentious work agreements and our current 457 visas. “The importation of workers was the subject of much debate in the Sydney press in the 1830s, [and] some commentators compared their employment contracts to slavery,” Linder told us. “These reports combined with accounts of mistreatment, resulted in the end of the short-lived scheme”. An employment contract between one such worker and their employer John Mackay is included in the exhibition.

The film, directed by Anupam Sharma, Indian Aussies: Terms and Conditions Apply, explores the ties that bind Australia and India, and what is means to be an Indian-Australian through interviews. The film doesn’t offer a conclusion to its topic, but rather personal perspectives, and as Linder states it was “included to demonstrate that the growing Indian Australian community has enormous diversity and strength”. Indian Link‘s Pawan Luthra is one of those included to offer his perspective.

Zenia Starr, Miss India Australia 2013 is also included in the film, as well as Professor Veena Sahajwalla (who also did a speech on opening night). Sahajwalla talks about how she gets told “You really are an Indian woman, so therefore shouldn’t you sometimes be wearing Indian saris? Well, I never really wore them when I was in India, why would I start wearing them in Australia? Because that… I mean, I feel that’s too restrictive”. During the film’s humorous ending, when the film pretends to end without talking about cricket, and then starts up again, Sahajwalla goes on to tell us that she doesn’t even like cricket, much to the horror of those that she knows.

Linder speaks of the film as being “very distinct from the historical components of the show and rightly so”. ANMM “would like visitors to leave the exhibition thinking of the future relationship between India and Australia,” and that is what we were left with.

Also linking Australia and India is the Colours of India, a lightshow projected onto the roof of the ANMM as part of Vivid Sydney. The museum commissioned Electric Canvas to produce the piece, and

rather than telling a story, it’s purpose is just to add a dash of colour, sound and movement to the building, through its association with the exhibition.

“The primary challenge is conveying complex history in a dynamic and interesting way for a range of visitors and layering the information,” says Linder of the challenges faced in the planning of East of India. However, after viewing the exhibition, it is clearly evident that they have been successful. By using a contemporary film and audio recordings, alongside historic objects, the early trade links between India and Australia are effectively conveyed. The stunning lights of Vivid Sydney on the ANNM’s roof only enhances this.

1 June – 18 August 2013

East of India – Forgotten trade with Australia

Australian National Maritime Museum

Colours of India – Vivid Sydney (4 May to 10 June, 6pm – 12am)

India Links in Oz that go back 200 years

Reading Time: 6 minutes