Indian artists explore the physical and philosophical at the 20th Biennale of Sydney

Autumn has arrived and the weather is caught between sunny days and long spells of rain. Why not embrace your inner art critic and explore the city as part of the Biennale of Sydney?

This year’s theme is ‘The Future Is Already Here – It’s Just Not Evenly Distributed.’ Working within the confines of this abstract premise, the art works and installations are hard-hitting, opening up a discussion about the uneven global distribution of wealth, technology, resources and human rights while also questioning ideas of citizenship and identity. Some works will demand your full attention and careful consideration, some will engulf you, and some will stare right back at you, dissolving the barriers between illusion and reality.

The Asia Pacific region’s largest contemporary visual arts event, this year’s Biennale of Sydney (running until 5 June) has divided its free exhibitions across seven major venues or ‘Embasssies of Thought’. When viewing the art, it is important to consider the locational features of each ‘embassy’ to relate to the works on display. There are also additional exhibition spaces where, according to the Biennale’s Artistic Director Stephanie Rosenthal, “The ‘in between’ spaces speak to one of the key ideas in this Biennale exploring the distinction between the virtual and the physical worlds”.

The Museum of Contemporary Art hosts the ‘Embassy of Translation’, the Art Gallery of NSW is the ‘Embassy of Spirits’, which explores religious and personal rituals, while the former convict settlement and shipyard at Cockatoo Island is the ‘Embassy of the Real’ offering “space for artists to explore how we perceive reality in our increasingly digitised era”. Other venues include Carriageworks (the ‘Embassy of Disappearance’), Artspace (the ‘Embassy of Non-Participation’), a roving bookshop (the ‘Embassy of Stanislaw Lem’) and first time venue Mortuary Station (the ‘Embassy of Transition’).

The Biennale 2016 has recovered from its lukewarm fate of 2014 and has been infused with a fresh lease of life. Featuring 83 artists from 35 countries across the world, there are five celebrated artists with Indian heritage or identity, showcasing their works.

Bharti Kher: Six Women

Painter and sculptor Bharti Kher’s ‘Six Women’, on display at Cockatoo Island, is a series of life-sized female sculptures, cast from real women who sat for her in her New Delhi studio. Her models are sex workers whose bodies, coated in plaster casts, set the unapologetic yet vulnerable tone for the art work. Looking at these women of various body types, with sagging breasts and protruding bellies, amid the vulnerability and vitality, she asks the viewer to question all myths and mythologies related to the body in contemporary culture.

“When you caress the skin and rub the plaster gently over and over so all the pores and creases are etched and filled with plaster, it’s like encasing and mummifying a living being,” Kher says. “You are trying to capture their breath, to find the imprint of their minds and thoughts, and the secrets of the soul… What the cast carries, only the model can give.”

“I have no idea what people think about when their heads are encased in plaster… The head is truly the most challenging and awkward part for them. It is always the last part. It involves complete trust and absolute calm in the model. Everyone seems to summon into being who they need to be to complete the casting,” Kher reflects. She depicts the body “as a literal and metaphorical site for the construction of ideas around gender, mythology and narrative”.

In the mid-2000s, she started creating a series of strangely beautiful, but quietly grotesque, hybrid sculptures of women fusing human and animal body parts. Kher described them as mythical urban goddesses, creatures who were born out of the contradiction of the idea of femininity or the idea of womanhood – “She is the goddess, the housewife, the mother, the whore, the mistress, the lover, the sister.”

Women’s vulnerability stems only in part from their nakedness. Her models were paid to sit for her, in a self-conscious transaction of money and bodily experience. Kher uses this creative process to pose questions such as, if the body can carry the memory of other bodies as well, what does this mean? Can a body carry narratives that don’t belong to it?

Located within the Embassy of the Real, her sculptures address the physicality and inherent vulnerability of the body and challenge our myths and perceptions of the body in contemporary culture.

Her artistic practice is highly diverse with regard to the use of materials, methods and subject matter. She often uses everyday objects, such as bindis and bangles, and “minimalism, abstraction and the readymade to engage with a range of ideas, including gender politics, language, mythology, hybridity, dislocation, transmogrification and narrative”.

Recently, Kher’s first solo exhibition in Australia ‘In Her Own Language’, showcasing a series of hybrid figurative sculptures, saris and bindis, was presented as part of the Perth International Arts Festival.

Raka Sarkhel

Neha Choksi: The Sun’s Rehearsal

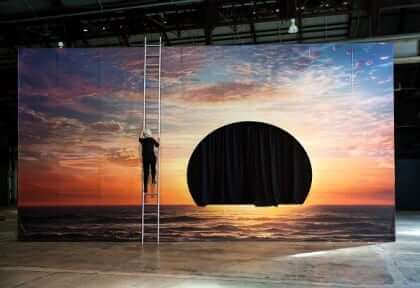

With an intrinsic fascination in creating artworks that explore abstract themes such as absence, loss, erasure and memory, Indian-American artist Neha Choksi’s latest piece ‘The Sun’s Rehearsal’ is on display at Carriageworks.

Neha’s billboard-sized artwork, in collaboration with Alice Cummins, is composed through multifaceted layers of seven contrasting sunset visuals featuring a dynamic fusion of warm colours. This layer is overlaid by a digitised graph of the sun in sunset. Alice Cummins adds further dimensionality to the artwork as she “directly engages the auratic installation of the sinking sun to ask urgent questions about the life of an ever-warming planet and the life of an aging body.”

“The image of a curtained sun came to me years ago when I was working on various photographs of the sun being burnt in different works,” Neha told Indian Link, as she described the development of ‘The Sun’s Rehearsal.’ “I decided to expand on the idea of the death of the sun as a companion piece to a series of birth related drawings I have been slowly making that refer to the scientifically recorded activity of the sun during the nine months I was in my mother’s womb and did not experience the sun’s light directly.”

The message of the artwork is centred on the hypothetical presage of the potential degradation of earth’s beauty. Choksi described the piece saying, “It is an encounter with a future loss, one that the sun stages daily, as if making ready for the very last time it will ever set. The curtained hollow is a stark reminder of and an anticipatory memorial to the moment of the final fatal sunset, beyond which there will be no human recollection of its beauty.”

Much of Choksi’s artwork is inspired by her upbringing, cultural heritage and current place of residency. “I love cities,” she said. “I am equally a creature of Los Angeles and Bombay. Both cities are home and both cities have contributed to creating who I am as an artist. My intellectual habits are decidedly rooted in my education in Los Angeles and New York.”

“My mother was Jain, and I reckon some part of Jainism’s philosophy of non-attachment has affected my desire to work with the push and pull of material and its absence,” Choksi said.

She also explained how she uses her own art for new ideas. “I learn from each new work I make and something from that process is continued into the next work.”

Neha Choksi has produced many artworks that have featured in galleries and exhibitions worldwide. She was also the first recipient of the Khoj TippingPoint India Commission. Her focus on creating art which captures the essence of erasure and absence comes down to a very simple, yet awe-inspiring phenomenon: “In a world full of ego and accumulation, the way forward is less.”

Namita Gohil

Dayanita Singh: Museum of Chance

The doyen of Indian photographers, the work of Delhi-based Dayanita Singh, ‘Museum of Chance’, 2015, which uses mixed media and variable dimensions, is on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Primarily consisting of black-and-white photographs, the work is part of ‘mobile museums’ that are an interconnected body of work, arranged as per themes such as chance, embraces and furniture. Through the processes of translation and retranslation, these museums can be endlessly edited, rearranged and displayed, casting new light on narrative and poetic possibilities in the process.

Nine accordion-fold book maquettes (small scale models) are placed in teak vitrines in the work titled ‘Kitchen Museum’.

“Secrets are very important to me and that’s another reason why I think I like museums – because they’re full of secrets and clues,” said Singh in an interview with Wall Street International. On her kitchen shelves are small Moleskines, the keepers of her experiences and travels.

Her contact sheets from a Hasselblad camera and medium format film are like a journal to her. “You keep finding new things on a contact sheet, depending on what sort of glasses you put on when you look at them.”

Singh grew up in a very organic house where things kept changing. For her the home and its architecture are about being able to change the space according to need, moods, or even the changing light. Singh’s museums also have a similar organic element in them. They are forever changing and rearranging themselves into conversation nooks where viewers can move in and out of these spaces. This portability and changeability adds a new dimension into the art of photography and its relationship with the viewer.

In her ‘Suitcase Museum’, also displayed at the MCA, two shirts hang by the hook on a wall. A rusted printing press stands exposed to the light of the sun. Ghostly make-shift curtains carved out from a dhoti sway in the breeze. There is a varying degree of poetry, melancholy and illusion in all these real images. The crisp black and creamy white images capture life unfolding like a dream.

As the photographer says on her website, “While I was in London I dreamed that I was on a boat on the Thames, which took me to the Anandmayee Ma ashram in Varanasi. I climbed the stairs and found I had entered the hotel in Devigarh. At a certain time I tried to leave the fort but could not find a door. Finally I climbed out through a window and I was in the moss garden in Kyoto.”

It is this fluidity and dream-like quality of real life that Dayanita Singh depicts through her images and their changing arrangement.

Raka Sarkhel

Sudarshan Shetty: Shoonya Ghar

Sudarshan Shetty’s Shoonya Ghar (Empty is this house), an-hour long video that demands your time and consciousness, is inspired by the 12th century saint-poet Gorakhnath’s couplet “shoonya gadh shahar shahar ghar basti, kaun sota kaun jage hai (If the city is empty, the fort is empty then where is the question of someone being awake or asleep?)

Born to a Yakshagana artiste father, Shetty is known for large-scale mechanical installations and multimedia works that investigate the duality of existence through a preoccupation with universal opposites. Death and renewal, desire and entropy, subtlety and spectacle, are evident in these installations that combine seemingly incongruous materials. In drawing together polar opposites, Shetty plays with expectation and perception, compelling the viewer to consider whether opposing forces can exist comfortably within a single space as mutually inclusive ideas.

At his solo show at the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi in January, Shetty notes how the poet enters “a hugely speculative space that includes an osmotic understanding of things”.

The installation involves a miniature model of the fort and lived spaces in ruins. The fort and the home (that merge into one another with their similar sounding Hindi identities of gadh and ghar) is seen as a passive witness to life and the characters dwelling in it. It explores the connection of the lived space with the consciousness of the people living in it.

In the video, being shown at the Art Gallery of NSW, Shetty has worked with nine actors, who embody the nine rasas integral to the Indian classical tradition, while the building is the silent protagonist.

“As you will see in the show, in the first look there is nothing fragile and everything is as solid as the built architectural form can be. However, once you have watched the hour-long video you will see the structure differently. You will perhaps be aware of its imminent coming apart after the period of the show is over, and that it becomes something else as you will know that these four architectural pieces are made in components and can be dismantled,” Shetty said in an interview with The Hindu. “These were built in my studio in Mumbai and dismantled and carried to a location which is an abandoned stone quarry. It is a space which is like a cavity in a hill made by taking away the stone to build elsewhere. Rebuilding these four structures as a set for a film, became symbolic – that these structures are rebuilt there only to be taken away to be shown at a gallery space, and will be dismantled again after the stipulated period of the show.”

Anthropologist and writer, Vyjayanthi Rao, explores this relationship between the building and the consciousness in an essay. “[Shetty’s] film involves building and construction alongside characters enacting scenes in which drama mobilises conventions of representing birth, death, dance, play, music and violence in local traditions of storytelling,” she writes.

The film also alludes to the binary of real and imagined spaces, much like the binaries of nirguna (the presence of an eternal all-pervading and omnipresent divine consciousness) and saguna (the manifestation of God in any form) of the Bhakti poet tradition it draws from.

Raka Sarkhel

Keg de Souza: Redfern School of Displacement

Born in Perth and now living in Sydney, self-styled “anarchitect” Keg de Souza uses her interdisciplinary art to explore spatial politics, in terms of both the physical and social.

After training in fine art and architecture, her interest in exploring the lived experiences of others and the impact this has on their interaction with various physical environments has often manifested itself in the use of inflatable architecture.

As de Souza told Real Time, “Inflatables were just naturally a way for me to be able to make something that was easily transportable. I was also thinking about utopias and nomadic architecture and the history of inflatables. They were often used as a symbol of radical architecture…But also I was thinking about what they can encompass with their temporality.”

‘Redfern School of Displacement’ creates a dialogue with the traditional owners of the land on which it takes place, the Gadigal People of the Eora Nation. As with much of her work, de Souza aims to create a site of collaboration, in this instance exploring the relationship between local people and their identity and connection with Redfern.

As she writes on her website, “By creating a platform for conversation and debate that explores the politics of displacement, RSD promotes learning as a useful tool to combat the forces of dispossession for the future.”

While her parents are originally from Goa, de Souza is very much a part of the Australian alternative and artistic scene. A member of Squat Space, a collective of twenty people living across several shopfronts, in the early 2000s de Souza and her comrades were part of highly publicised campaign to keep their lodgings and legitimise their living space.

The artist has noted that it is through this experience that she was drawn to investigation of social and spatial environments through her art.

As part of RSD, participants are requested to acknowledge their personal privileges and actively make space for ‘other’ voices.

With a focus on collective learning, RSD is a space to explore and discuss. Topics will include: dispossession and displacement through enforced and prioritised language; colonisation and the displacement of Indigenous residents from the Redfern area; housing and homelessness; displacement caused by conflict and climate change; and displacement through gentrification.