The city formerly known as Madras is traditional yet thirsting for change. Chennai remains a place of contradictions

The New York Times chose Chennai as one of the top 52 best destinations in its 2014 travel edition. It calls Chennai, quite aptly, “A national cultural capital”.

Chennai is home to several dance and music schools like Kalakshetra, and the Music Academy for Bharatanatyam and Carnatic music respectively, and literally hundreds of other ‘sabhas’ all regularly holding performances around town almost all year round, especially during the ‘music deason’. During the music festival – the largest of its kind anywhere in the world – the city is abuzz with performances from all over India including lecture demonstrations, seminars, talks and workshops on a whole gamut of cultural subjects.

The city is alive all year round with numismatic clubs, stamp clubs, philosophy, history, literary and book clubs galore, all with their own offerings, making it truly one of the most intellectually ‘connected’ cities in the world.

This writer, during her annual or biannual visits to the city has attended a stamp collectors’ monthly meet, the regular meetings of the group Tatvaloka, which holds talks on a range of subjects from Chola temples to theology; and attended a 10 day free course offered by the Samskrita Bharati and a swathe of volunteers who have dedicated their lives to promoting Sanskrit, conducting Sanskrit classes and camps throughout the city for free.

There are also historic temples aplenty, including the Kapaleeswarar Temple, built in the name of Lord Shiva, the ancient Parthasarathy Temple, the Kesava Perumal and the Madhava Perumal temples in Mylapore, the Marundeeswarar Temple in Tiruvanmiyur and other ancient temples like the ones in Tiruvottriyur, Vadapalani, Porur, Nazarethpettai. The list is too long to be mentioned here.

Then there is the historic ‘town’ area which grew up around Fort St George, the oldest British colonial settlement in India, built in 1640. There is the impressive 1000 Lights Mosque, the San Thome Church and other imposing Indo-Saracenic architecture like the University of Madras, the Museum, or the buildings on Pantheon Road, or the majestic colonial ones like the Ripon Building.

The city is rich in cultural, religious, gastronomic and sporting heritage and highlights include the largest classical music festival in the world, a remarkable array of cuisines, both native and imported, from the crisp dosa to spicy chicken 65; a passion for cricket, tennis and chess (the best tennis and chess players hail from this city), and the best filter coffee on the planet.

Besides its excellent handicraft outlets, temple jewellery and Kanchipuram silks, new sites and developments make this city especially enticing. There is a swathe of new and trendy clubs, boutiques, artists’ colonies, bookshops and restaurants.

The Annual Chennai Book Fair and its public libraries, especially the Connemara Public Library, cement Chennai’s claims as one of the most intellectually stimulating cities in India.

Looking at books about Chennai, one cannot go past S Muthiah’s Madras Discovered, first published in 1981 and later republished as Madras Rediscovered. This, together with Bishwanath Ghosh’s Tamarind City, gives a wonderful portrait of Madras and Chennai (as it started to be called after 1996). Ghosh points out that while in other big cities in India tradition stays mothballed in trunks, to be taken out during festivals and weddings, Chennai is both traditional and tech savvy at the same time – indeed these are two inseparable sides to Chennai.

Chennai is modern India’s oldest city: both Muthaiah and Ghosh (who has made Chennai his home) remind us that almost every modern institution in India – from the army and civil service, to the judiciary and the Congress,

city councils to engineering, and medicine – traces its roots to Madras’s Ford St George, the first British settlement in India.

The Madras Regiment, the first and oldest in the Indian Army, was founded by the East India Company traders to protect Fort St George in the 17th Century. Indeed, the seminal British victory at the Battle of Plassey was secured by the British largely with the help of this regiment, 80 per cent of whom were raised by Robert Clive in this southern city.

The surveys – precursors to the Survey of India department – began at this time; Charles Trevelyn, governor of Madras, founded the Indian Civil Service; the first municipality was founded in Madras in 1688; the first joint stock companies were founded in George Town in 1689, and soon afterwards, came the Bank of Madras. Most important of all, the Indian National Congress was born on the banks of the Adyar River in Madras when A.O. Hume mooted the idea at a meeting of the Theosophical Society.

Chennai, Not Madras (2006), by A R Venkatachalapathy, who is a Professor at the Madras Institute of Development Studies (and formerly from the National University of Singapore and JNU), is a slightly different account of the city. The author, an academic who has written widely in both English and Tamil, looks at the tension between the Madras of the colonial era and the Chennai of the 21st century world.

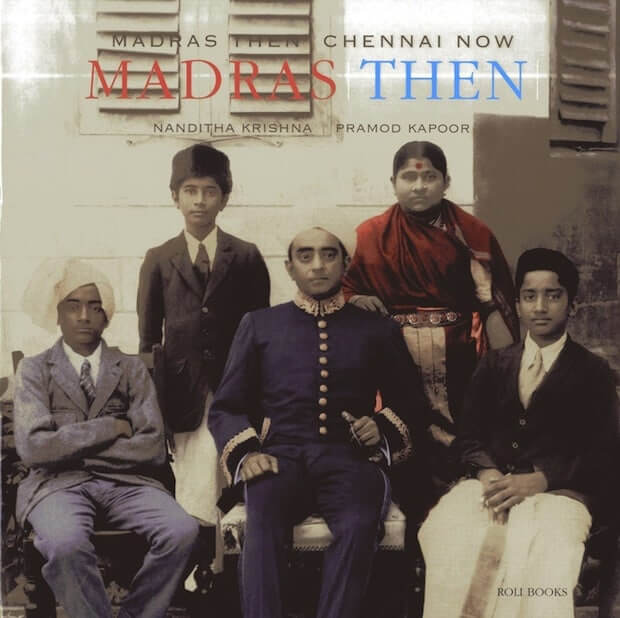

A similarly titled booked Madras Then, Chennai Now, by Nandita Krishna and Tishani Doshi, published this year, also describes the city as one of dualities: conservative yet irreverent, traditional yet forward thinking, steeped in nostalgia, yet thirsting for change. This is a beautifully published coffee table book packed with rarely seen photographs and painstakingly researched text. The photographs were sourced from public and private collections – from the British Library and from prominent families like the Mudaliyars and the CP Ramaswami clan. The book is divided into two halves – one featuring pictures from the British Raj era, and the other contemporary photos. Doshi, a poet and novelist, could have settled anywhere in the country but she chose Chennai, “the city where amazing people quietly do amazing things”.

Nirmala Lakshman’s Degree Coffee By the Yard is another attempt to bring together the Madras of yore and the Chennai of now. The two, she argues, are so intertwined that it is impossible to tell them apart. The history of the city is populated with fascinating characters: writers, builders, thinkers, British traders, luminaries and rogues, freedom fighters and political leaders who changed the city’s political milieu. In independent India, the political life of Madras was marked by battles for equality, the demolition of unjust caste structures and a remarkable spirit of secularism, all of which the author vividly brings to life.

Other novels located in Chennai include Tirumurti’s Chennaivasi. The most evocative passages in the book are those that lovingly recreate the sights, smells and sounds of Chennai past and present – the Madras Central Railway Station, waking up to the strains of Suprabhatham, putting together a kolu during Navratri, a visit to a Nadi astrologer. Chennaivasi brings out the paradox of Chennai’s Tam Brams (Tamil Brahmins) – their strange cocktail of professional modernity and personal traditionalism.

Then there is The Healing by Gita Aravamudan which was released by Harper Collins in 2008. It is a novel that spans several generations and seven tumultuous decades. The story swirls around Shanti Nivas a sprawling family property scheduled to be demolished and transformed into apartments. Past loves and unresolved conflicts clash with the reality of the present day as the various members of what was once a large family come to terms with their changing lives.

Priyamvada Purushottam’s The Purple Line, set in the 2000s, is both contemporary and nostalgic. Sumeetha’s The Perfect Groom and Mala Kumar’s The Paths of Marriage are set largely in Chennai – in Mylapore and the slums of Chennai respectively. In Srividya Natarajan’s book No Onions Nor Garlic – a hilarious Wodehousian tale set in Chennai – the city comes alive.

Abhimanyu Rajarajan’s IT romance and thriller When Shall We Meet Again encapsulates all that is uniquely Chennai; it has a software billionaire, a programming de-bugger and a Swamij (Chennai has produced quite a few). Chetan Bhagat’s Two States, also captures the zeitgeist of this very distinctive city.